The Neuroscience of Free Will: Are We Really in Control?

Neuroscience and Philosophy | Daniel Nirmalaraj

You press the snooze button once more. Instead of reaching for a tea, you reach for a coffee. Instead of studying, you choose to text your friend. You have to make choices every day, moment by moment, or so it seems. However, what if these choices had already been made before you even knew about them? The unsettling notion that free will, or our capacity to select our acts, may not exist is something that modern neuroscience is exploring. It’s not just science fiction. Our decisions may be predicted by brain scans seconds before we even realise it. Are we truly in charge then? Or are we only observing our own actions?

We must first define free will before we can question if it exists. In philosophy, free will is the ability of a person to make choices and act without reference to past events or the external universe. Given the laws of physics and neuroscience, the concept is more complicated from a scientific standpoint, and it is considered controversial whether such freedom actually exists or not. It is sometimes framed more practically as the capacity to deliberately direct actions [1]. There are two defined forms of cognitive processing: conscious control and automatic processes. Automatic processes are rapid, habitual, and unconscious, whereas conscious control entails planned, focused thinking and attention. Automatic processing is effortless, and occurs outside of human consciousness, whereas controlled processing involves conscious awareness, effort, and mental resources [2]. The philosophical spectrum of free will debate centres on determinism, compatibilism, and libertarianism. According to determinism, there is no place for true free will because everything, including human actions, is predestined by prior causes [3]. Compatibilism, also referred to as soft determinism, contends that actions can be both freely chosen and causally determined so long as they are consistent with the person’s internal motives. On the other hand, libertarianism maintains that humans have true free will, allowing them to choose different courses of action, and that free will and determinism are irreconcilable [3]. However, neuroscience has complicated this discussion in ways that philosophers did not expect.

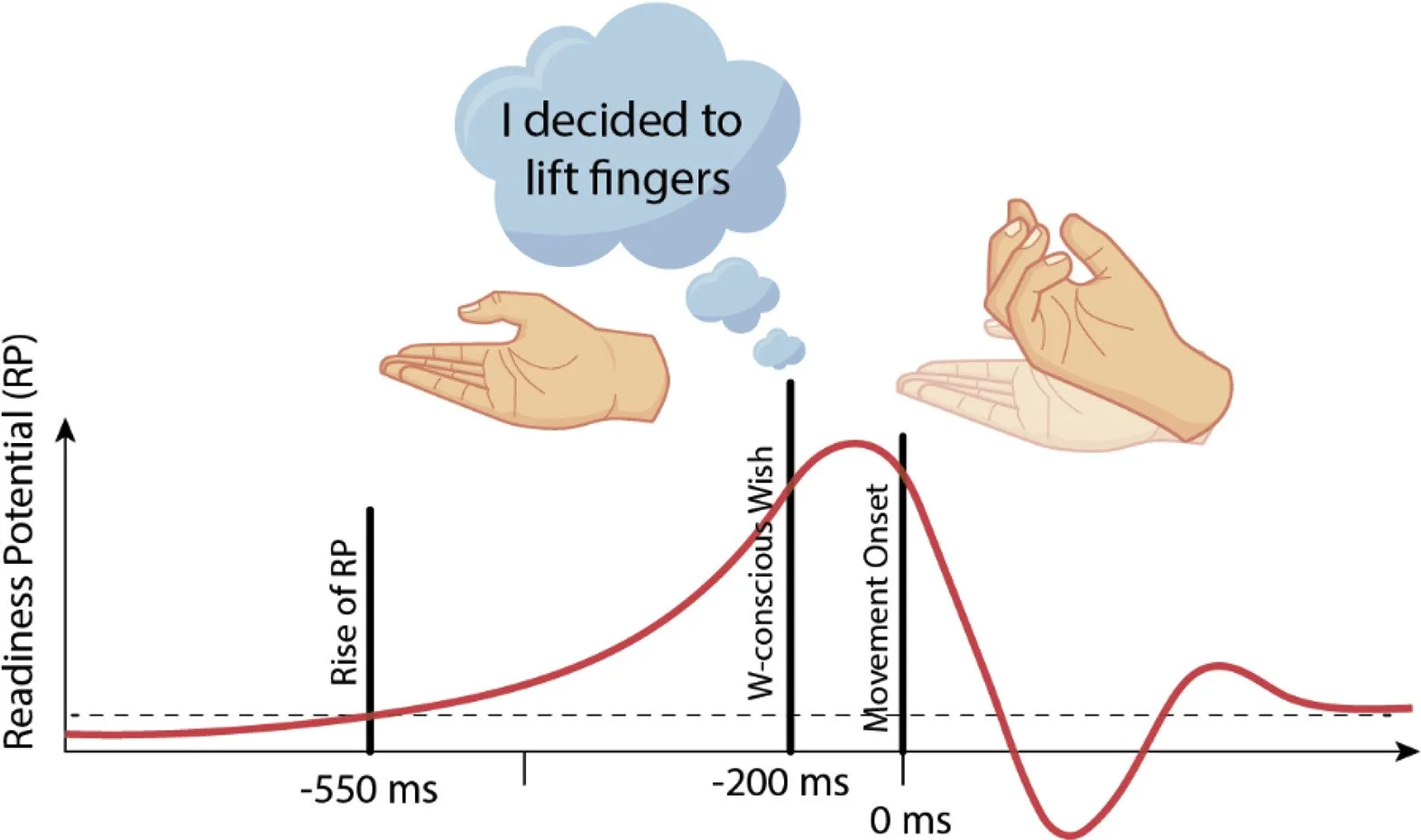

Benjamin Libet, a neuroscientist in the 1980s, carried out a famous experiment to determine whether the conscious knowledge of a decision was preceded by brain activity associated with that movement. As illustrated in Figure 1, Libet instructed his human participants to consciously decide to flex their wrists at will, without informing him, and monitored their brain activity. The participants noted the timing of each conscious decision by the position of a clock hand when they first became aware of their intention. According to his research, a spike in brain activity for the participants manifested, on average, 350 milliseconds prior to their claimed conscious decision to move [5]. This spike is known as a “readiness potential,” which is a gradual accumulation of electrical activity in the brain, particularly in the motor regions [6]. These results indicated that the brain had already started the action prior to participants being conscious of making a decision. This discovery prompted Libet to contend that voluntary actions are a secondary, later event rather than the result of our conscious awareness or “will” to act. The action is subconsciously started by the brain, and our conscious perception of free will may be a retrospective interpretation of those neurological processes [5].

Figure 1: Schematic of readiness potential in terms of time in the Libet Experiment about the time of free will, and time of deferent events on the Libet Experiment. The rise of readiness potential occurs 350ms before the conscious intention (feeling of free will) [4].

Subsequent studies from different researchers have produced similar findings. These studies indicated that brain activity can anticipate decisions up to several seconds before a person is fully aware of making them, mirroring Libet’s Experiment. In 2008, a study utilising functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) discovered it was possible to predict the choices participants would make up to ten seconds prior to their conscious decision, demonstrating that decision-making is greatly influenced by subconscious brain activity [7]. Critically, these findings suggested that human perception of conscious control may simply be the brain’s way of reporting what it has already decided. The implications of Libet’s results are considered controversial in the wider scientific community. Brain activity preceding conscious awareness is understood as the unconscious initiation of movement in Libet’s experiment, however, critics state it may really be preparatory brain activity rather than a conscious intention to move. They contend that readiness potential is a build-up of potential resulting in inaction, rather than reflecting a decision [8].

Schurger et al (2012) theorised that the brain accumulates random fluctuations until a threshold is achieved. This process is more akin to a “neural coin toss” than a deliberate command [9]. While Libet’s experiment was revolutionary in its investigation of the relationship between conscious will and brain activity, there were methodological limitations. A major question presented was whether the experiment’s artificial, lab-based activities were truly representative of real-world choices. Particularly, these tasks lacked the intricate social, emotional, and contextual elements underpinning decisions in everyday life. Thus, critics raised doubts about the simplicity of tasks in the study. The complexity of the decision-making process for choosing a spouse or job greatly differs from flicking your wrist at will. Is it truly possible to draw conclusions about morality and individual choices based on simple wrist flicking?

Why do we feel in control even when our brains make subconscious decisions? One idea behind this is post hoc realisation; the propensity to develop explanations for choices or actions after they have taken place, even when such explanations do not accurately represent the true motivations underlying decisions. Essentially, the brain makes a decision, for which we create a narrative to justify it to ourselves and others [10]. Daniel Wegner, a pioneering social psychologist, revealed that our perception of conscious volition is a “post hoc illusion”, with the brain performing an action and justifying it by fabricating a suitable narrative. In his book The Illusion of Conscious Will, Wegner puts forward the case that the sensation of conscious choice is an illusion, rather than the actual cause of that action. He contends that, although we believe our conscious thoughts directly drive behaviour, the brain starts activities before we become aware of them [11]. This notion presents itself in the case of blindsight and split-brain patients, where both groups demonstrate behaviours that occur without conscious knowledge. When split-brain patients react to stimuli that are only perceived by one hemisphere, the other hemisphere will create a plausible reason behind the action, even if it does not have access to the stimulus [12]. These experiments demonstrate that much of what motivates us occurs subconsciously, particularly in the context of blindsight, where people react to visual information they are unable to consciously see [13].

Regardless, many philosophers and scientists are unprepared to completely reject the notion of free will. Compatibilists say the “self”, or conscious mind, is still a crucial component of the decision-making process even if brain activity precedes conscious awareness [14]. Compatibilists view free will as solely requiring the ability to act in accordance with motivations, goals, and values. This theory encompasses the brain’s unconscious processing as a natural element of our functioning, posing no threat to our freedom. Planning, self-control, and introspection are all cited as possible neurological foundations of free agency and are critical functions of key decision-making areas of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex. As a “central executive”, the prefrontal cortex coordinates cognitive processes and directs behaviour in line with internal goals [15]. It enables the foresight of future outcomes, control over impulsive behaviour, and the ability to weigh different courses of action, providing the basis for making choices and exercising our feelings of agency. Therefore, these systems contribute towards our ability to delay gratification, think about repercussions, and align actions to our identities. After all, this is what we mean by freedom, is it not?

Perhaps the question is not “do we have free will?”, but rather “how much control do we really have?” At its core, the issue in the free will versus determinism argument relates to different levels of control and influence over our actions. Free will should be thought of as a spectrum, rather than classified in black-and-white terms. Various factors, including stress, trauma, exhaustion, and mental disease may reduce a person’s ability to think and act. Conversely, mindfulness, education, and awareness may promote open-mindedness and positively impact the thoughts and actions an individual has. By understanding and comprehending when and where our free will is restricted, we can develop new tools to expand it.

So, did you decide to read this article? Or did your neurons actually lead you here before “you” even realised it? Neuroscience calls into question our conceptions of free will, but it does not have to erase them. It challenges us to reconsider what freedom means, viewing it as a biological power to influence our own lives over time. Perhaps the ultimate goal of free will is not about being free, but becoming aware.

[1] A. Lavazza, “Free Will and Neuroscience: From Explaining Freedom Away to New Ways of Operationalizing and Measuring It,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 10, 2016, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00262.

[2] P. Fisher, “Clinical Psychology: An Information Processing Approach,” Elsevier, 2012, pp. 510-516.

[3] J. B. Miles, “‘Irresponsible and a Disservice’: The integrity of social psychology turns on the free will dilemma,” British Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 205-218, 2013, doi: 10.1111/j.2044- 8309.2011.02077.x.

[4] M. Jamali, M. Golshani, and Y. Jamali, “A proposed mechanism for mind-brain interaction using extended Bohmian quantum mechanics in Avicenna’s monotheistic perspective,” Heliyon, vol. 5, no. 7, p. e02130, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02130.

[5] B. Libet, C. A. Gleason, E. W. Wright, and D. K. Pearl, “TIME OF CONSCIOUS INTENTION TO ACT IN RELATION TO ONSET OF CEREBRAL ACTIVITY (READINESS-POTENTIAL),” Brain, vol. 106, no. 3, pp. 623-642, 1983, doi: 10.1093/brain/106.3.623.

[6] A. Schurger, P. B. Hu, J. Pak, and A. L. Roskies, “What Is the Readiness Potential?,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 558-570, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2021.04.001.

[7] C. S. Soon, M. Brass, H.-J. Heinze, and J.-D. Haynes, “Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain,” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 543-545, 2008, doi: 10.1038/nn.2112.

[8] P. Alexander, A. Schlegel, W. Sinnott-Armstrong, A. L. Roskies, T. Wheatley, and P. U. Tse, “Readiness potentials driven by non-motoric processes,” Consciousness and Cognition, vol. 39, pp. 38-47, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2015.11.011.

[9] A. Schurger, J. D. Sitt, and S. Dehaene, “An accumulator model for spontaneous neural activity prior to self-initiated movement,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, no. 42, pp. E2904-E2913, 2012, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210467109.

[10] J. S. Summers, “Post hoc ergo propter hoc: some benefits of rationalization,” Philosophical Explorations, vol. 20, no. sup1, pp. 21- 36, 2017, doi: 10.1080/13869795.2017.1287292.

[11] D. M. Wegner, The Illusion of Conscious Will. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2002

[12] N. Marinsek, B. O. Turner, M. Gazzaniga, and M. B. Miller, “Divergent hemispheric reasoning strategies: reducing uncertainty versus resolving inconsistency,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 8, 2014, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00839.

[13] B. De Gelder, N. Humphrey, and A. J. Pegna, “On the bright side of blindsight. Considerations from new observations of awareness in a blindsight patient,” Cerebral Cortex, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 42-48, 2025, doi:10.1093/cercor/bhae456.

[14] G. Gomes, “Free will, the self, and the brain,” Behavioral Sciences & the Law, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 221-234, 2007, doi: 10.1002/ bsl.754. [15] M. B. Jurado and M. Rosselli, “The Elusive Nature of Executive Functions: A Review of our Current Understanding,” Neuropsychology Review, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 213-233, 2007, doi: 10.1007/s11065-007- 9040-z.

Daniel is a Biomedical Science student doing his Masters involving lens physiology, with interests that extend to neuroscience and philosophy. Outside of his studies, Daniel enjoys playing Tennis, the guitar and watching football.