Scales of Connection: Loneliness and Social Cohesion

Social Health and Complex Systems | Ricki Rebecca Ridgway

Social relationships are fundamental to human health and well-being [1], yet these crucial human connections have recently been classed as a global and public health concern [2]. There are many facets of social connection, two of which are social cohesion and loneliness. Although each refers to different levels of relationship—collective vs individual—they are both associated with mental and physical well-being, and both have a range of diverse influences that are contextually dependent [2], [3].

There is growing concern across the globe and within Aotearoa about the rising rates of loneliness [2-4]. The COVID-19 pandemic brought this into focus, but the trend towards disconnection has been escalating since well before this extended event [4]. Social cohesion is on our national radar as well, as highlighted by a report issued in April 2025 [5]. Responses analysed from the 2,631 participants showed that social cohesion among New Zealanders was lower than Australian ratings on nearly every measure. The World Health Organisation released a report in July 2025 that shows social disconnection is already widespread [2]. Here in Aotearoa we face a challenge to strengthen our social ties and address the broader social fragmentation that is reflected in both loneliness and cohesion measures.

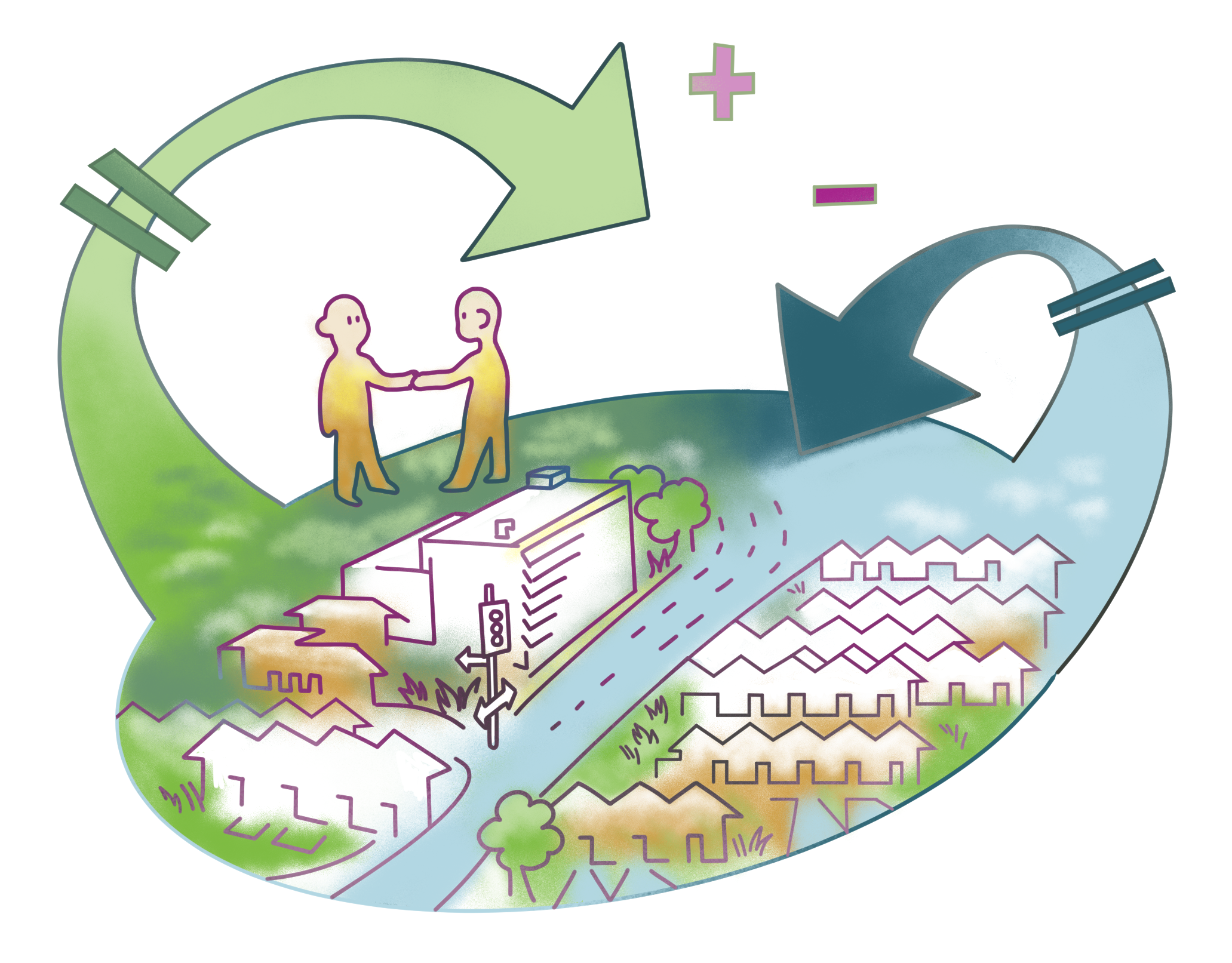

Figure 2: Artistic representation of how individuals are embedded in complex systems they often cannot see. Artwork by the author.

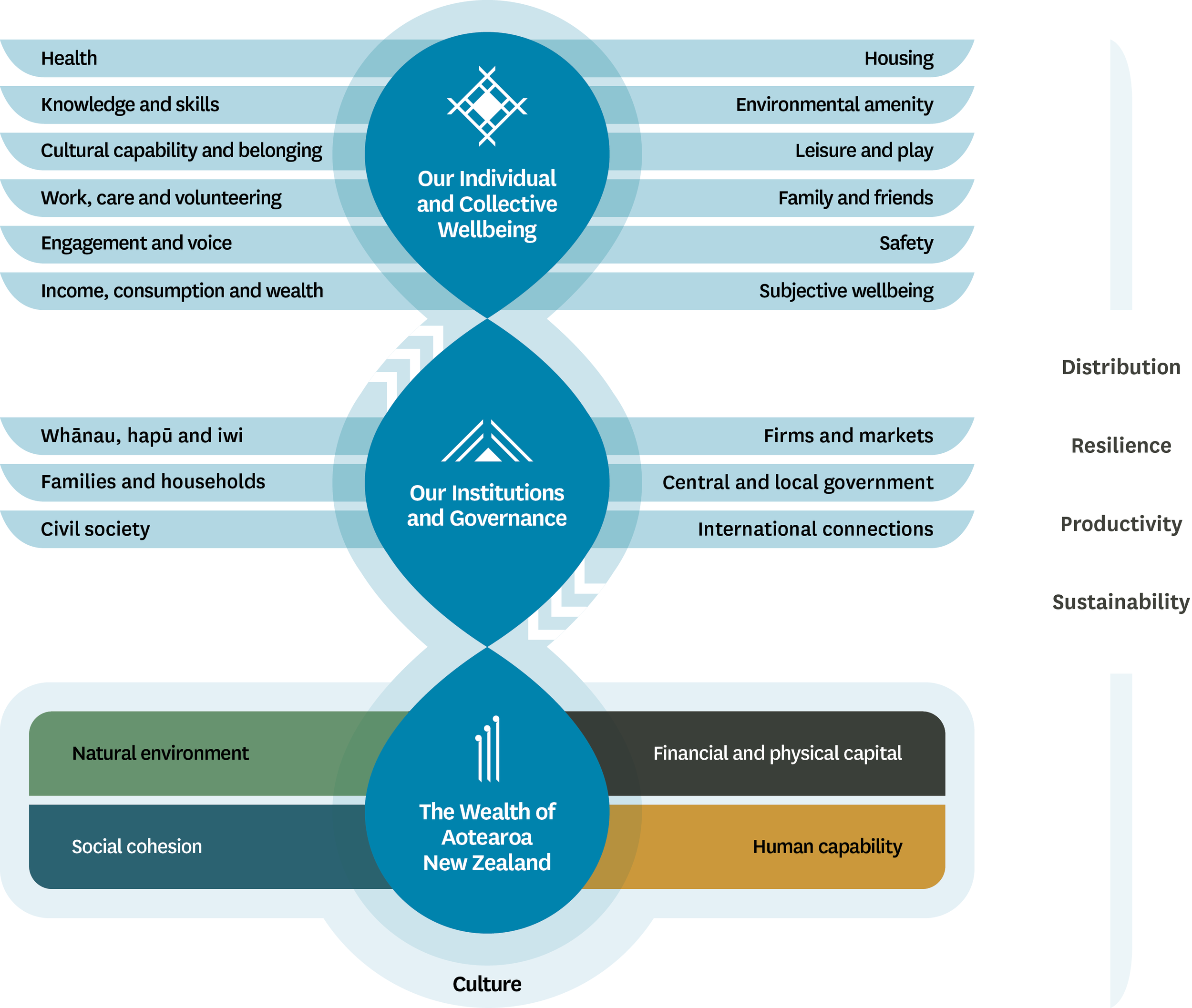

Figure 1: New Zealand Treasury’s Living Standards Framework. [6]

Glossary

Complex social systems: “Systems in which individuals frequently interact in many different contexts with many different individuals, and often repeatedly interact with many of the same individuals over time.” [23, p.1787]

Loneliness: “The unpleasant experience that occurs when a person’s network of social relations is deficient in some important way, either quantitatively or qualitatively.” [11, p. 31]

Social cohesion: “The willingness of diverse individuals and groups to trust and cooperate with each other in the interests of all, supported by shared intercultural norms and values.” [6, p.16]

Social health: The quantity and quality of relationships in a particular context to meet an individual’s need for meaningful human connection [1].

Social Cohesion: The Glue of Communities

Social cohesion has been counted as a key component of Aotearoa New Zealand’s collective wealth [6]. This concept can be thought of as a “glue” that holds communities together and is one dimension of social connectedness [2], [5], [7]. Social cohesion could be considered an emergent property of societies, in that it indicates the behaviour of groups. A reliable nine-point social cohesion and belonging scale used to assess neighbourhood attitudes includes statements such as “I feel like I belong in this neighbourhood” and “People in this neighbourhood generally get along” [8]. Analysis and modelling of a large number of responses could be used to infer macro level trends in a population’s attitudes and beliefs.

Social cohesion is not about everyone being the same. Rather, working well together is strengthened in part due to our differences. A study of Italian students’ attitudes toward multiculturalism found that a sense of unity depended on a recognition of and dialogue about diversity within the ingroup as well as accepting differences with outgroups [9]. The New Zealand Treasury’s Living Standards Framework acknowledges that different people and communities will define well-being according to their values [6]. Although social cohesion does not necessitate specific values such as tolerance, this emergent condition is grounded in cultural norms and influenced by compliance with civic values: willingness to acknowledge and action shared values [7]. Communities with higher cohesion tend to show lower levels of crime, greater resilience in the face of disasters, and more stable health outcomes across the lifespan [2]. We could say things are going well when societies exhibit an amount of cohesiveness that allows its members to work for some mutually assured benefit despite differing world views, identities, and values [10].

Loneliness: A Public Health Challenge

Loneliness has traditionally been assessed as an individual and subjective feeling that indicates some level of separation from those around you [3]. Loneliness is not the same as being alone. It is an involuntary experience characterised by a perceived lack of meaningful social connections and negative emotions stemming from this discrepancy [11]. Since loneliness is a personal feeling of being disconnected from other people, it can be felt in a variety of different contexts and expressed in nuanced ways. Unlike social isolation, which can be measured by frequency of social contact, loneliness is personally determined; one may be surrounded by people yet still feel lonely if those relationships lack intimacy or authenticity.

Dimensions of loneliness can be understood through both category and duration. Different expressions or sources of loneliness may take on social, emotional, or existential forms [12], and can also vary in intensity and duration. Transient loneliness, such as missing a friend or experiencing a brief rejection, is not inherently harmful and may even be adaptive by motivating social connection [13]. Chronic loneliness, by contrast, refers to a severe, prolonged, and deeply distressing state with profound impacts on health and well-being [4], [11]. When left unaddressed, this long-term disconnection contributes to a range of negative health outcomes [2], [13], [14]. Moreover, increasing isolation and a mistrust in being heard can extend beyond the individual, fostering wider social alienation. Social isolation, defined as an objective lack of sufficient relationships or interactions, often intersects with the subjective experience of loneliness, producing feedback loops that magnify disconnection and erode trust [2].

Some Linking Threads Loneliness is often framed as an individual mental health issue, examined primarily by psychologists and health professionals [13]. Social cohesion is most relevant for meso and macro levels of society, tied to social capital, inequality, or community resilience [5], [6]. Loneliness and social cohesion, although often studied separately, both signal social connectedness [2]. While loneliness typically describes an individual and personal phenomenon, and social cohesion relates to broad community structures, both are partially defined by the presence or lack of belonging and trust [10]. Understanding their complexity is crucial for evaluating interventions, shaping policy, and guiding future research [2], [15], [16]. Addressing loneliness therefore requires reinforcing the social structures and collective practices that generate cohesion [17]. In other words, the problem belongs to the health system as a whole.

If cohesion is macro-level, then wouldn’t micro- and meso-level encounters—the everyday interactions between neighbours, in schools, or across community organisations—be the disguised opportunities for developing trust, acceptance, and engagement? These small-scale exchanges can accumulate to strengthen societal cohesion [15], offering practical sites for intervention [17]. Yet traditional Western models of healthcare often privilege linear causation, focusing narrowly on individual risk factors and treatments while overlooking the dynamic, systemic processes that sustain connection [18].

Public Health Systems as Complex Systems

To consider public health issues as complex systems is to frame them as dynamic, with multiple factors interacting in nonlinear ways. An intervention designed in one part of the system may generate indirect or unintended effects elsewhere. The groundwork for this perspective can be traced to General Systems Theory [19] and expanded through Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory [20], which describes human development as shaped by reciprocal interactions between individuals and their layered environments. The adaptation of systems thinking to address public health has become more accepted within the last decade, reflecting frustration with the limitations of methodological individualism and reductionism, and growing recognition of health inequalities as systemic problems [18], [21].

Public health systems are multi-layered, shaped by interactions across interpersonal relationships, institutions, and environments [18], [21]. Framing loneliness and social cohesion through complexity theory highlights that disconnection is not simply an individual problem but part of a dynamic social system. A systems lens can assist the examination of various knitted mechanisms that produce and sustain social (dis)connection. Applying this perspective to public health frameworks could support the design of interventions and policies that address root causes more often than isolated symptoms.

The following segments illustrate four characteristics of complex social systems as they apply to public health, loneliness, and social cohesion.

Feedback Loops

Feedback loops describe how changes within a system can intensify or regulate further change, showing the interconnectedness of causes and effects [22], [23]. Reinforcing loops amplify decline: loneliness can lead to withdrawal from community life, weakening networks and further reducing opportunities for connection [11-13]. Unless interrupted, this cycle accelerates loneliness and erodes cohesion. By contrast, balancing loops can strengthen resilience: individuals under stress may seek supportive environments that reduce strain, thereby stabilising well-being. Everyday places such as shops and cafés can serve as balancing mechanisms by satisfying the basic need to belong [8]. Complex systems include such loops and interwoven relationships that linear models often overlook [18], [22]. These dynamics can produce unanticipated consequences and outcomes strongly dependent on prior events [24].

Emergent Properties

Emergence refers to properties that arise from the interaction of system components but cannot be reduced to a single part [22], [23]. Social cohesion is emergent; it develops through patterns of interaction, shared narratives, and collective practices [6]. A neighbourhood where residents greet one another and join in local activities tends to foster relationships of trust that no single action could guarantee. Conversely, absent or hostile interactions foster distrust even when individuals value community. Recognising cohesion as emergent highlights why loneliness cannot be solved simply by telling people to “make friends”; without supportive structures, individual efforts remain insufficient.

Spreading Dynamics

Emotions, behaviours, and norms spread through networks [25]. Loneliness is not necessarily confined to individuals but can diffuse across networks; individuals influence those around them, creating clusters of (dis)connection that may extend up to three degrees of separation [26]. In 2019, “Neighbour Day” engaged 300,000 people through 437 events in 276 suburbs across Australia [27]. It included a variety of activities, gatherings, games, and checking on vulnerable neighbours. Surveys conducted before, immediately after, and six months following the event indicated that hosting a neighbourhood event significantly enhanced identification with the local community, which in turn supported greater social cohesion, reduced loneliness, and improved well-being.

Scaling

Scaling in social networks refers to people and places at different levels of closeness and can be leveraged when designing interventions. Urban design and planning is one domain that could benefit from a strategic consideration of how social infrastructure, such as third spaces, is utilised in residential areas to promote social connection [2], [8]. Healthy Families New Zealand (HFNZ), an equity-driven, place-based community health initiative in Aotearoa, is one example of how scale can be used to orient a public health system [16]. Rather than thinking of “scaling up” as just expanding interventions to larger populations, HFNZ uses this term to indicate the joining of communication channels and collaboration across nested social systems. A recent evaluation of HFNZ suggests that by shifting individual, group, and organisational mindsets towards a more systems-thinking, relational paradigm, decision makers will be better equipped to respond flexibly to possible determinants of health across the scales of our societies [16].

Key Takeaways

This article positions systems thinking as a holistic framework that can help us more clearly see the dynamics in interventions that integrate health care, community initiatives, and social policy to build resilient, connected societies. Any one of the examples described in this article could be expanded upon, but the main point here is to practise applying this analytic lens to a currently relevant issue. Social health is a recently recognised pillar of health, and thus investigation continues. Complex problems do not always require complex solutions, but we do need to shift the way we think about loneliness in communities, and how national and health services aim to address social well-being and cohesion. Systems thinking is just one lens that can be adopted to help us consider ways to move forward. It can provide a framework for considering the interdependencies of social complexity. Key takeaways include:

Widening our purview from individualistic to relational models of health: Recognising that well-being depends on social ties will benefit discourse surrounding social cohesion and wide-spread loneliness.

Reframing solutions from short-term fixes to dynamic adaptations: Feedback loops, emergence, spreading, and scaling can help explain how small shifts ripple across networks.

Seeing integrated responses as essential: Opportunities to support a sense of belonging and trust are embedded right across the system, in healthcare, social services, urban planning, and community initiatives.

Figure 3: Artistic representation depicting the features of complex systems: feedback, scale, spread, and emergence. Artwork by the author

Figure 4: Representation of the socioecological model with potential solutions to strengthen social connection at different scales. [2]

[1] D. M. Doyle and B. G. Link, “On social health: history, conceptualization, and population patterning,” Health Psychol. Rev., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 626–655, 2024, doi: 10.1080/17437199.2024.2314506.

[2] WHO Commission on Social Connection, “From loneliness to social connection: charting a path to healthier societies,” World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, June 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www. who.int/groups/commission-on-socialconnection/report/.

[3] M. H. Lim, R. Eres, and S. Vasan, “Understanding loneliness in the twentyfirst century: an update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions,” Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol., vol. 55, pp. 793–810, June 2010, doi: 10.1007/ s00127-020-01889-7.

[4] N. Pai and S.-L. Vella, “COVID-19 and loneliness: A rapid systematic review,” Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry, vol. 55, no. 12, pp. 1144–1156, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1177/00048674211031489.

[5] S. Eaqub and R. Collins, “Social Cohesion in New Zealand,” Helen Clark Found., Auckland, New Zealand, Apr. 1, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://helenclark. foundation/publications-and-medias/ social-cohesion-in-new-zealand/.

[6] New Zealand Treasury, “The Living Standards Framework 2021,” Wellington, New Zealand, Oct. 28, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.treasury.govt. nz/publications/tp/living-standardsframework-2021.

[7] J. Chan, H.-P. To, and E. Chan, “Reconsidering Social Cohesion: Developing a Definition and Analytical Framework for Empirical Research,” Soc. Indic. Res., vol. 75, pp. 273–302, Jan. 2006, doi: 10.1007/s11205-005-2118-1.

[8] R. Zahnow, “Social infrastructure, social cohesion and subjective wellbeing,” Wellbeing Space Soc., vol. 7, p. 100210, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j. wss.2024.100210.

[9] C. Pagani, “Diversity and social cohesion,” Intercult. Educ., vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 300–311, Jun. 2014, doi: 10.1080/14675986.2014.926158.

[10] P. Gluckman, A. Bardsley, P. Spoonley, C. Royal, N. Simon-Kumar, and A. Chen, “Sustaining Aotearoa New Zealand as a cohesive society,” Koi Tū Centre for Informed Futures, Auckland, New Zealand, Dec. 13, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://informedfutures.org/social-cohesion/.

[11] D. Perlman and L. A. Peplau, “Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness,” in Personal Relationships, vol. 3, S. Duck and R. Gilmour, Eds., London, UK: Academic Press, pp. 31–56.

[12] L. Cristine, “Loneliness: Understanding the Complex Factors and Causes,” Int. J. Sch. Cogn. Psychol., vol. 11, no. 7, p. 391, July 2024, doi: 10.35248/2469-9837.24.11.391.

[13] L. Mansfield et al., “A conceptual review of loneliness across the adult life course (16+ years),” What Works Wellbeing, London, UK, July 2019. [Online]. Available: https://whatworkswellbeing.org/product/ loneliness-conceptual-review/.

[14] J. Holt-Lunstad, T. B. Smith, M. Baker, T. Harris, and D. Stephenson, “Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A MetaAnalytic Review,” Perspect. Psychol. Sci., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 227–237, Mar. 2015, doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352.

[15] R. Peace and P. Spoonley, “Social Cohesion and Cohesive Ties: Responses to Diversity,” N. Z. Popul. Rev., vol. 45, no.1, pp. 98– 124, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://communityresearch.org. nz/research/social-cohesion-and-cohesive-ties-responses-todiversity/.

[16] A. Matheson et al., “Building a systems-thinking community workforce to scale action on determinants of health in New Zealand,” Health Place, vol. 87, p. 103255, May 2024, doi: 10.1016/j. healthplace.2024.103255.

[17] O. Sagan, “Loneliness, Social Cohesion, and the Role of Art Making,” Societies, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 237, Sept. 2025, doi: 10.3390/soc15090237.

[18] R. Atun, “Health systems, systems thinking and innovation,” Health Policy Plan., vol. 27, no. suppl_4, pp. iv4–iv8, Oct. 2012, doi: 10.1093/ heapol/czs088.

[19] L. von Bertalanffy, General System Theory. New York, NY, USA: George Braziller, 1968.

[20] M. Crawford, “Ecological Systems Theory: Exploring the Development of the Theoretical Framework as Conceived by Bronfenbrenner,” J. Public Health Issues Pract., vol. 4, no. 2, p. 170, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.33790/jphip1100170.

[21] S. Chughtai and K. Blanchet, “Systems thinking in public health: a bibliographic contribution to a meta-narrative review,” Health Policy Plan., vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 585–594, May 2017, doi: 10.1093/heapol/ czw159.

[22] H. Rutter et al., “The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health,” Lancet, vol. 390, no. 10112, pp. 2602–2604, Dec. 2009, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31267-9.

[23] T. M. Freeberg, R. I. M. Dunbar, and T. J. Ord, “Social complexity as a proximate and ultimate factor in communicative complexity,” Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B, vol. 367, no. 1597, pp. 1785–1801, July 2012, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0213.

[24] A. V. Diez Roux, “Complex Systems Thinking and Current Impasses in Health Disparities Research,” Am. J. Public Health, vol. 101, no. 9, pp. 1627–1634, Sept. 2011, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300149.

[25] A. L. Hill, D. G. Rand, M. A. Nowak, and N. A. Christakis, “Emotions as infectious diseases in a large social network: the SISa model,” Proc. R. Soc. B, vol. 277, no. 1701, pp. 3827–3835, July 2010, doi: 10.1098/ rspb.2010.1217.

[26] J. T. Cacioppo, J. H. Fowler, and N. A. Christakis, “Alone in the crowd: The structure and spread of loneliness in a large social network,” J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., vol. 97, no. 6, pp. 977–991, Dec. 2009, doi: 10.1037/a0016076.

[27] H. Beilby, J. Spinks, T. Cruwys, and C. Rose, “Addressing loneliness through a scalable neighbourhood connection campaign: an evaluation of Neighbour Day using an Australian population-based control and causal propensity score-based approaches,” J. Environ. Psychol., vol. 105, p. 102659, Aug. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j. jenvp.2025.102659.

Ricki is completing a postgraduate diploma in psychology with the intent of continuing to a masters in 2026. Her interests are generally within the realm of community, social and critical health psychologies. Through the implementation of non-fiction graphic narrative Ricki aspires to uplift and support community voices, as well as communicate complex information simply.

Ricki Rebecca Ridgway - PGDipSci, Psychology

Anna is a Principal Investigator at Te Pūnaha Matatini, Aotearoa New Zealand’s Centre of Research Excellence. She has a wide array of expertise in public health policy, complex systems research, and social determinants of health. Her research applies complex systems thinking, tools, and practices to address systemic challenges, particularly health inequalities. She also leads the national evaluation of Healthy Families NZ and teaches in courses for the Bachelor of Health programme at VUW.