Rongoā Māori is more than an alternative to medicine. To Māori, the indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand, it is medicine.

Rongoā Māori and Indigenous Health | Ruth Prasad & David Lu

Rongoā Māori is often thought of as a complementary and alternative medicine. However, this should not be the case. Rongoā Māori is a way of life that encompasses Māori values, customs, and healing practices that have been observed in Aotearoa for more than a thousand years. Moreover, there is interconnection between the land and Rongoā Māori, where land holds strong importance within Māori identity, as it embodies Papatūānuku. To Māori, the land leads to the creation of individuals and shapes the way they express their cultural, spiritual, emotional, physical, and social well-being. Aotearoa and the ongoing processes of colonisation have harmed Rongoā Māori, such as the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 which prevented healing and traditional practices based on spiritual connectedness. Rongoā Māori is built on the foundation of indigenous cultural values and beliefs, and these labels nullify the indigenous ontological and epistemological foundations of traditional healing.

“Ko Au te Whenua, ko te Whenua Ko Au, I am the land and the land is me.”

The Importance of Rongoā Māori in Health Care

Rongoā Māori derives from mātauranga Māori and is part of a Māori worldview [1]. Within health, there have been countless articles and reports regarding the implementation of Rongoā Māori. However, it often reduces Rongoā Māori to merely herbal medicine treatments [1], even though it is also known as a way of life. This completely disregards its cultural significance and harms a beautiful aspect of a Māori worldview. In this article, we aim to introduce the importance of Rongoā Māori, what it is, and how it can benefit the future of Aotearoa’s healthcare system. “Nāu te rourou, nāku te rourou, ka ora ai te iwi: through your basket of knowledge and my basket of knowledge, the collective basket of knowledge will expand.

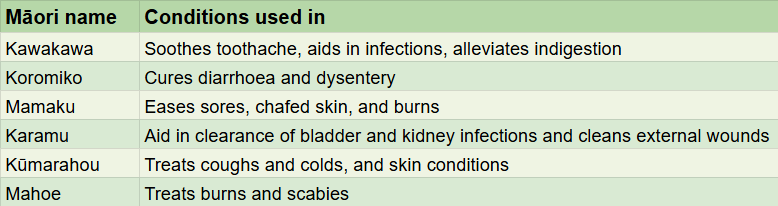

Table 1: Traditional Māori Herbs and their Uses (Made using information from [9]).

What is Rongoā Māori?

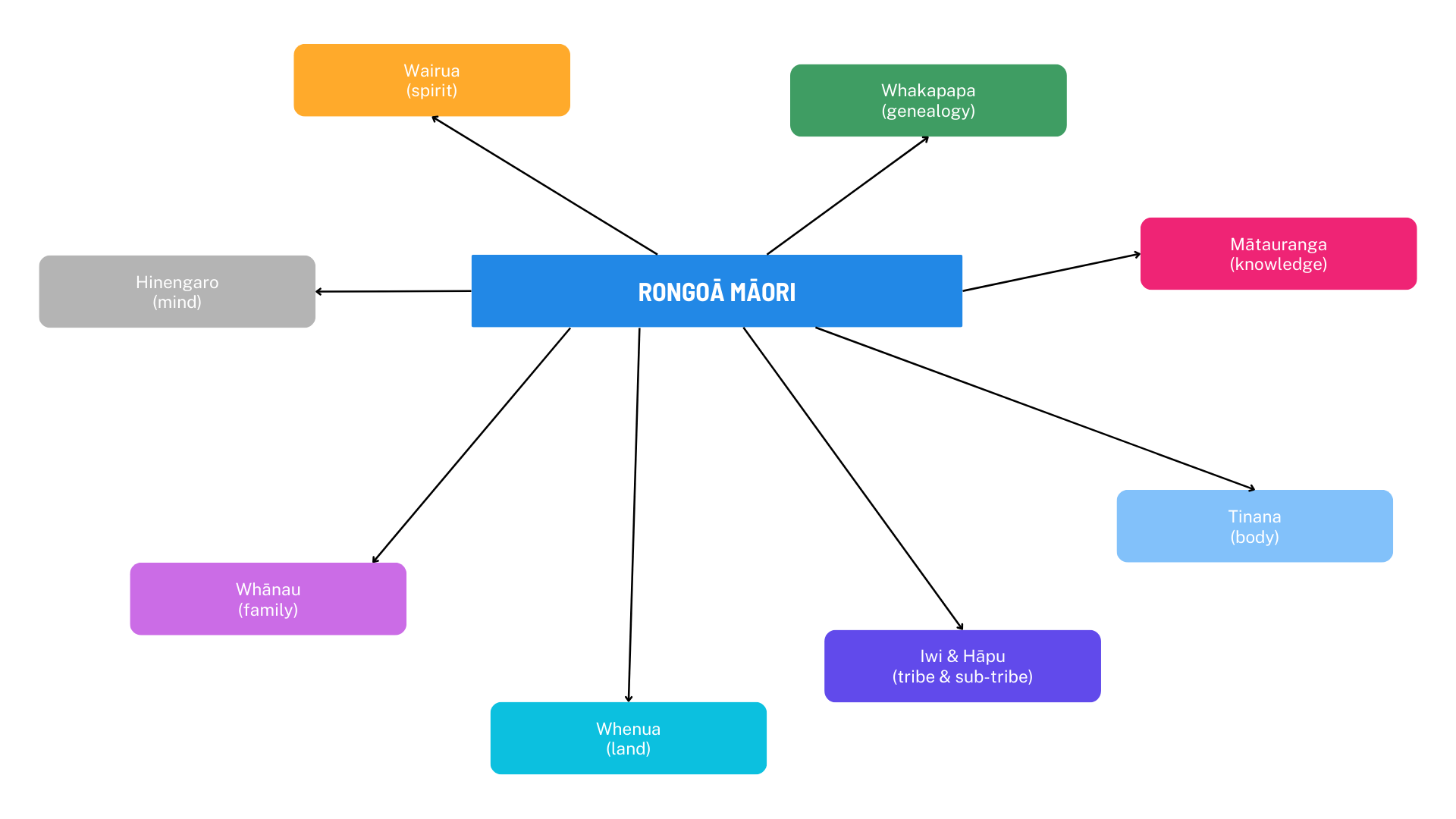

Rongoā Māori is a way of life that has been practised for centuries, encompassing ritenga and karakia (incantations and prayers), rongoā rākau (physical remedies from plant materials), mirimiri or romiromi (physical touch or massage), wai/huawai (use of water or streams) and matakite (sight or prophecy) [2]. The whenua (land) is a crucial component of Rongoā Māori as it focuses on the practice of reciprocity with Papatūānuku (earth mother). It is a taonga tuku iho (ancestral treasure) of intergenerational healing of the people and their cultural identity and connection to Māori worldview, alongside the protection of the whenua, spiritual interconnection, and mauri (life force) of all life [1]. The properties of Rongoā Māori go beyond the physical and chemical interventions that arise from herbal medicine, with the focal point being its strong emphasis on strengthening the connection of mauri, plant, and healer. Moreover, “ka ora te whenua, ka ora te tangata: when the land is healthy, the people are healthy” goes back to Rongoā Māori. This includes the sustainable use of the whenua and moana (sea), but also the protection and appropriate use of mātauranga Māori and te reo Māori [1]. Therefore, it is important that when discussing the implementation of Rongoā Māori into healthcare we do not reduce a complex modality to one aspect, as this disregards the cultural significance, way of life, and Māori worldview that all weave into what Rongoā Māori is.

Rongoā Māori in Healthcare Settings

In Aotearoa, Rongoā Māori in healthcare has a confronting history to uncover. It has faced challenges such as the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 which suppressed Rongoā Māori [3-4]. The Act was introduced by Māori MP James Carroll and passed in 1907 with the support of all four Māori MPs at the time, targeting self-appointed tohunga who lacked the training of traditional tohunga by Māori elders [3-4]. Influential Māori doctors at the time such as Māui Pōmare and Te Rangi Hīroa also supported the bill [3-4]. James Carroll and Māui Pōmare both had good intentions, as they had introduced and passed Acts that allowed Māori to buy back ancestral land and compensate iwi that had lost land within their communities, and they both played important roles in improving Māori living conditions, Māori public health, and Māori education [3, 6]. The Tohunga Suppression Act was passed with the intent to help protect Māori communities from being misled or defrauded by ineffective medicines and treatments that were deemed potentially harmful [3-4]. Furthermore, it was passed alongside the Quackery Prevention Act of 1908, which had the aim of preventing fraudulent and dishonest medical practices in general, as there were growing concerns about fraudulent medicine [4]. However, as with many bills and acts, the Tohunga Suppression Act produced unintended consequences. Although only a handful of tohunga were charged under the Tohunga Suppression Act, it led to the obscuring of traditional Māori healing due to the belief that practising it would lead to prosecution, which then led to the steep decline in Rongoā Māori practice [4]. In 1962, this harmful act was superseded by the Māori Welfare Act [5]. In modern day Aotearoa, Western medicine is the mainstream method of achieving health outcomes, while Rongoā Māori developed into a niche that is mostly sought after within the Māori community [4]. However, concerns are being raised in the modern healthcare context about how the Western-dominated medicine setting impacts the accesibility of heathcare for Māori, as well as how it may affect cultural identity and Māori well-being [5].

Rongoā Rākau is a branch of Rongoā Māori that focuses on healing through the use of herbs and the natural flora of Aotearoa New Zealand. These herbs can be applied to the healthcare setting and there are a myriad of traditional Rongoā Māori herbs that are evidenced to be effective in the treatments of health conditions. It has been well documented that natural flora endemic to New Zealand have been used in Māori health for centuries, if not millenia, and has been credited as the backbone of Māori healthcare before settlers introduced new diseases [3, 4, 6]. One of the most well known Rongoā Rākau herbs is Mānuka, or Leptospermum scoparium. Mānuka flowers can be made into tea, and its pollen is used to make Mānuka honey. Tea tree oil can also be extracted from the leaves and bark of the Mānuka tree, and studies have shown that it has antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antifungal effects on animal models [6]. Mānuka honey has also been shown to have antibacterial effects, particularly on gram-positive bacteria, due to the methylglyoxal compounds within the honey [7-8]. These methylglyoxal compounds disrupt the fimbriae and flagella of bacteria, preventing adhesion and motility respectively [8].

There are also Rongoā Māori herbal therapeutics that are potentially able to treat more modern diseases due to common active compounds that are shared with known drugs. An example of this is type II diabetes, where Māori and Pacific people are overrepresented in negative health outcomes. Herbs often used in Rongoā Māori have compounds that are known to alleviate the symptoms of diabetes. For example, Kūmarahou, a shrub tree endemic to New Zealand, has multiple compounds such as quercetin and saponin that alleviate diabetic symptoms via antioxidant activity [9]. Quercetin in particular has been shown to have anti-inflammatory characteristics in animal models in vivo, which is a common side effect of diabetes and obesity, but its effects on humans are yet to be elucidated [10].

Atopic Dermatitis also disproportionately impacts Māori and Pacific children, with an incidence rate of 45% compared to the general hospital catchment population of 35% and 12% for those under 15 years in Aotearoa [10]. Common treatment measures within Western medicine include antibiotics and advice on the use of diluted bleach baths with intermittent applications of mupirocin ointment [10]. However, treatment may often be ineffective with no improvement observed from antiseptics between patients colonised with Staphylococcus aureus [9]. As of now, the cure for atopic dermatitis remains unknown and topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors are prescribed as a maintenance therapy [11]. The nature of these, especially for young children, can often be irritating or potent with longterm use [10]. In Rongoā Māori, dermatitis is also treated through herbal means. A trial was conducted with 3% kānuka oil cream over a six week period with a control cream that had similar healing properties to kānuka oil, and it was concluded that kānuka oil did significantly better at improving the condition in comparison to the control cream [12].

Although Rongoā Rākau (herbal medicine) is often the main focus as treatment for ailments in Rongoā Māori, it is still important to recognise Rongoā Māori beyond herbal remedies. For Māori, health and well-being are inextricably interconnected with the health of the physical environment and emotional ties, which highlights the importance of maintaining balance and harmony with nature [13]. Mauri is believed to run through everything that connects us to our natural environment, and thus interactions with divine and ancestral beings connected to the natural realm help foster the diagnosis of an illness through the surrounding landscapes [13]. It is therefore essential that we recognise Rongoā Māori within the healthcare context as a way of life rather than solely focusing on singular aspects, or as complementary medicine. The spirituality within Rongoā Māori is not necessarily different from Western beliefs. Rather, it encapsulates a world of connections that flows within the concept of wholeness [13]. This spirituality allows the perspective of understanding that as humans we are only one small part of a far larger ecosystem, and that humanity must maintain the health of our surroundings and thus the natural equilibrium of all things [13]. As mentioned earlier, Rongoā Māori encompasses various treatment options and these all stem from a focus on treating the illness at the source, or preventative measures rather than simply trying to cure symptoms at their onset. This ensures that healing targets the mental, physical, and spiritual well-being of a patient to enable awareness around maintaining a healthy equilibrium [13]. Therefore, implementing Rongoā Māori into mainstream health must also consider the more holistic approaches to treatment and how that can coincide with biomedical interventions.

The Impact of Cultural Practices in Healthcare

The implementation of Rongoā Māori into mainstream healthcare is a challenging one. As of now, Rongoā Māori healing is practiced outside of mainstream healthcare, which is partially attributed to limited funding provided by the government [14]. Rongoā rākau is omitted from government funding as safety and quality concerns were not easily monitored, so protection for consumers and providers could not be guaranteed [14]. Thus, most Rongoā practitioners conduct Rongoā Māori independently of government and medical sectors in order to practise, protect, and preserve the cultural integrity of Rongoā Māori [14].

When discussing impacts of cultural practices in healthcare, their efficacy and effectiveness are often scrutinised. Rongoā Māori has a rich and lengthy history of beneficial utilisation, and was well developed before European contact [14]. Within Rongoā Māori was detailed knowledge of human anatomy and physiological principles, recognition of the healing properties of various plants, and a firm understanding of the mind being separate from the body [14]. However, in contrast to most medical knowledge, Rongoā knowledge and information were not documented by formal means but rather passed down from one generation to the next [14]. It can be noted that the efficacy in Rongoā Māori is highlighted by the retention of treatment that has addressed particular health conditions such as dermatitis with kawakawa, as noted over a period of time [14]. Thus, efficacy has been determined through practice rather than controlled research environments, which may become a limitation within Rongoā Māori in terms of accessing public funding and regulation for practice.

Therefore, in order to implement Rongoā Māori, a good way to measure efficacy is needed, and this can be done with three qualitative aims: the alleviation of spiritual, emotional, physical, or social distress; improved mental, spiritual, physical, and social well being; and lifestyle modifications, including achievement of balance, reviewing living patterns, consolidation of identity, and development of positive relationships [14]. Thus, efficacy can be measured through a Māori worldview that encapsulates Rongoā Māori as a whole.

A recent trial was conducted where interpersonal relationships between traditional healing and Western medical practitioners in Rongoā/medical collaboration were examined to draw conclusions around whether successful collaboration and implementation is feasible.

Table 2: Rongoā Māori as a Holistic Approach to Health (Made using information from [13]).

This trial was unique, as selected patients were both consulted with a Rongoā Māori healer and doctor with an increased consultation time of 45 minutes compared to the often quick 15 minute consultations common in Western medicine [15]. The trial concluded with feedback from the participants showing significant favour towards a more collaborative approach between Rongoā Māori and Western medicine, as it increased quality of care, enabled patients to have autonomy over health, and built rapport [15]. However, there are still challenges that impact the direct implementation of Rongoā Māori without proper funding and consideration, such as a lack of consultation time and training, lack of defining clear roles, fears relating to professional identity, and poor communication [15]. These all need to be clearly addressed and considered before taking steps to ensure implementation is done properly. Within this trial, an argument often arose against Rongoā Māori that it does not relate to all ethnicities [15]. However, the trial recruitment was open to non-Māori to demonstrate that Rongoā Māori has a role in health for all ethnicities, and the significant amount of positive responses from the trial support this notion [15]. The impact of Rongoā Māori in healthcare is important to consider, but it is equally critical to consider how a Rongoā Māori incorporation into healthcare should be done in full and equal partnership and in alignment with the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi [15].

Recommendations

Rongoā Māori incorporates a complex set of traditional cultural beliefs and practices which should not be brushed over when it comes to implementing it into mainstream health practice. Although this article has provided a broad introduction to Rongoā Māori and a few uses, it is important to understand that Rongoā Māori is a way of life and considering how it can be incorporated into a Western medical system must be considered carefully. Thus, further research is needed.

Additionally, it is crucial to acknowledge that Māori identification with the land reinforces cultural and social connection [4]. Rongoā Māori is interconnected with the land, and simply implementing Rongoā Māori within healthcare is therefore not enough. Other systemic factors must also be addressed, such as alienation from ancestral land due to the processes of colonisation [4]. Therefore, there must be active steps taken for Māori to reconnect with their lands and to care for them, which ties into supporting Rongoā Māori healing for the health and well-being of both people and land [4].

There is great positive finding in the trial that was regarding partnership and collaboration with Rongoā Māori and Western medicine. It is important to note that although both methods of healing contrast one another, through collaboration and partnership the efficiency and quality of care for patients can be significantly improved. Thus, we hope that there can be more research with integrated Rongoā Māori alongside mainstream health rather than keeping them independent from one another.

The importance of Rongoā Māori within healthcare is high, and we acknowledge the significance of implementing traditional values and beliefs with contemporary practices of healing, as well as how Rongoā Māori could potentially cause paradigm shifts in health. Once again, we would like to emphasise that Rongoā Māori is not just about healing; it is also a way of life that continues to uphold cultural values in indigenous healing in a society where health is dominated by a biomedical lens. Rongoā Māori is crucial to tangata whenua’s health, healing, and well-being, and it can also be transformed into a great healing journey for us all.

Itiiti rearea, teitei kahikatea ka taea

Although the rearea is small it can ascend the lofty heights of the Kahikatea tree.

[1] G. Mark, A. Boulton, T. Allport, D. Kerridge, and G. Potaka-Osborne, “‘Ko Au te Whenua, Ko te Whenua Ko Au: I Am the Land, and the Land Is Me’: Healer/Patient Views on the Role of Rongoā Māori (Traditional Māori Healing) in Healing the Land,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 14, p. 8547, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148547.

[2] A. Ahuriri- Driscoll, “HE KŌRERO WAIRUA: Indigenous Spiritual Inquiry in Rongoā Research,” MAI Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 33–44, May 2014, [Online]. Available: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/4e5aae1f-379a-4027-a863-fe43deeaf22e/content

[3] Rhys Jones, ‘Rongoā – medicinal use of plants’, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/rongoa-medicinal-use-of-plants (accessed 18 January 2025)

[4] “Demystifying Rongoā Māori: Traditional Māori Healing,” Best Practice Journal New Zealand, no. 13, pp. 32–36, May 2008, [Online]. Available: https://bpac.org.nz/bpj/2008/may/docs/bpj13_rongoa_pages_32-36. pdf

[5] J. Koea and G. Mark, “Is there a role for Rongoā Māori in public hospitals? The results of a hospital staff survey,” New Zealand Medical Journal, vol. 133, no. 1513, Art. no. ISSN 1175-8716, Apr. 2020, [Online]. Available: https://nzmj.org.nz/media/pages/journal/vol-133-no-1513/ is-there-a-role-for-rongoa-maori-in-public-hospitals-the-results-of-ahospital-staff-survey/ddf5d7c29e-1696474977/is-there-a-role-forrongoa-maori-in-public-hospitals-the-results-of-a-hospital-staff-survey.pdf

[6] Alan Ward. ‘Carroll, James’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https:// teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2c10/carroll-james (accessed 18 January 2025)

[7] M. Lis-Balchin, S. L. Hart, and S. G. Deans, “Pharmacological and antimicrobial studies on different tea-tree oils (Melaleuca alternifolia, Leptospermum scoparium or Manuka and Kunzea ericoides or Kanuka), originating in Australia and New Zealand,” Phytotherapy Research, vol. 14, no. 8, pp.623– 629, Jan. 2000, doi: 10.1002/1099- 1573(200012)14:8.

[8] E. Rabie, J. C. Serem, H. M. Oberholzer, A. R. M. Gaspar, and M. J. Bester, “How methylglyoxal kills bacteria: An ultrastructural study,” Ultrastructural Pathology, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 107–111, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.3109/01913123.2016.1154914.

[9] J. H. Koia and P. Shepherd, “The Potential of Anti-Diabetic Rākau Rongoā (Māori Herbal Medicine) to treat Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) Mate Huka: A review,” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 11, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00935.

[10] S. Chen, H. Jiang, X. Wu, and J. Fang, “Therapeutic effects of quercetin on inflammation, obesity, and type 2 diabetes,” Mediators of Inflammation, vol. 2016, pp. 1–5, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1155/2016/9340637.

[11] S. E. Hill, A. Yung, and M. Rademaker, “Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and antibiotic resistance in children with atopic dermatitis: A New Zealand experience,” Australasian Journal of Dermatology, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 27–31, Dec. 2010, doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00714.x.

[12] N. Shortt et al., “Efficacy of a 3% Kānuka oil cream for the treatment of moderate-to-severe eczema: A single blind randomised vehicle-controlled trial,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 51, p. 101561, Jul. 2

[13] B. Marques, C. Freeman, and L. Carter, “Adapting Traditional Healing Values and Beliefs into Therapeutic Cultural Environments for Health and Well-Being,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 426, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010426

[14] Ahuriri-Driscoll, Baker, Hepi, Hudson, Mika, and Tiakiwai, “The Future of Rongoā Māori: Wellbeing and Sustainability,” Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd & Ministry of Health, FW06113, Sep. 2008. Accessed: Jan. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/064fd078-d860- 4887-bf2f-87cdb2081321/content

[15] J. Koea, G. Mark, D. Kerridge, and A. Boulton, “Te Matahouroa: a feasibility trial combining Rongoā Māori and Western medicine in a surgical outpatient setting,” New Zealand Medical Journal, vol. 137, no. 1597, pp. 25–35, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.26635/6965.6417.

David is a third year medical and surgical student with diverse interests in research, law, and health. His research areas include cancer therapeutics and genetics, neuroscience, and medical school outcomes.

David Lu - MBChB

Ruth is a third year Health Science student with a passion for working towards achieving equity based healthcare. She hopes to continue to do research within health. Her research interests are pathology, indigenous health, equity and medical health outcomes.