Think Fast, Choose Faster: The Neuroscience of Decision-Making

Neuroscience and Decision-Making | Aariana Rao

Decision-making is driven by neural mechanisms involving key structures such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, striatum, and dopaminergic pathways. The interaction between cognitive and emotional systems is examined, particularly in the context of stress, which affects executive function and decision control. Additionally, the influence of reward processing and the brain’s reward circuitry on decision-making is discussed, highlighting how motivation, emotion, and cognition converge to guide behavior. Insights into how past experiences and emotional responses shape decision-making are also considered, offering a comprehensive understanding of the biological foundations of human behavior.

Unraveling the Science of Decision-Making

Every action a person takes, whether trivial or life-changing, is driven by a complex network of neural pathways that underpin the process of decision-making. From the routines that shape daily life to the choices that alter the course of an individual’s future, human existence is fundamentally defined by the decisions made, both consciously and unconsciously. Neuroscientific research suggests that decision-making is not governed by logic alone, but is profoundly influenced by factors such as emotions and stress. A deeper understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying decision-making offers valuable insight into the biological foundations of human behaviour.

Decision-making is a complex, high-level cognitive function shaped by feedback from past experiences and environmental context. In the 1960s, Ward Edwards outlined three essential features of decision-making: (1) it involves a series of actions taken over time to achieve a goal, (2) these actions are interdependent, and (3) both the environment and the outcomes of these actions continuously change [1, 2]. From a biological perspective, these processes are largely encompassed by the perception-action (PA) cycle - the continuous flow of information regulating a person’s interaction with, and adaptation to, their environment [3].

On a structural level, decision-making engages several key brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), amygdala, and striatum of the basal ganglia [4-6]. The PFC is vital for higher-order executive functions, including planning, judgement, and behavioural regulation. Historical insight into its role came from the famous case of Phineas Gage, a rail worker who survived a severe brain injury when an iron rod passed through the front of his brain. However, this injury only affected his personality and behaviour, not other higher-order functions such as memory and motor skills. Thus, this incident highlighted the importance of the ventral and medial parts of the PFC in behavioural control and decision-making [7-10]. Subsequent research has consistently demonstrated that damage to the PFC results in poor judgement, impulsivity, socially inappropriate behaviour, and chronically poor decision-making [7, 11-14].

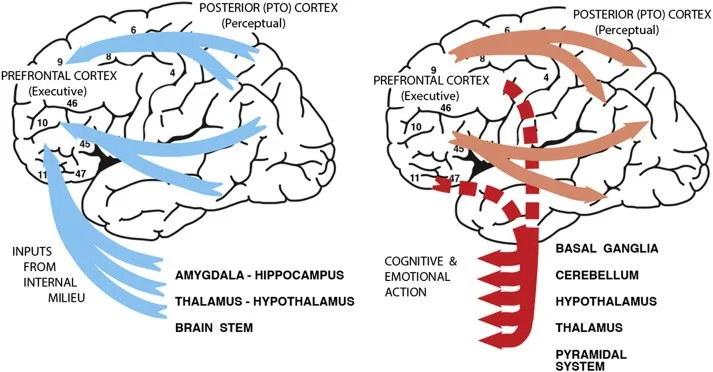

Figure 2: A visualisation of the major cerebral sources of input (blue) and targets of output (red) in the cognitive and emotional perception-action cycles. Subcortical inputs from the internal milieu predominantly enter the orbital prefrontal cortex. The interaction between the prefrontal cortex, subcortical structures, and feedback from internal and external environments constitutes the emotional perception-action cycle, which operates alongside the cognitive cycle depicted in Figure 1 [3].

Figure 2 illustrates how subcortical inputs from the internal milieu - the internal environment of bodily fluids regulating cellular function - enter the PFC via limbic structures. It is involved in evaluating and responding to both internal and external stimuli. These inputs typically converge in the orbital PFC and the connections form the emotional PA cycle, which parallels the cognitive PA cycle [3]. These two cycles continuously interact, with emotional information modulating cognitive processing and vice versa. The emotional PA cycle incorporates structures including the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, and ventral striatum, which are essential for evaluating the value and motivational significance of current and anticipated stimuli [3-6].

The Amygdala: Emotions and Decision-Making

The amygdala, located in the medial temporal lobe, plays a central role in emotional regulation and processing. It comprises two distinct functional and anatomical components, extensively interconnected with both cortical and subcortical regions, enabling it to influence diverse neural systems [17, 18]. One of its key functions involves associating stimuli with emotional value. This is particularly relevant for decision-making, as the amygdala triggers autonomic responses to emotionally salient stimuli, including monetary rewards and punishments. Individuals with amygdala dysfunction function lack these autonomic responses, impairing their ability to use somatic markers that typically guide future decisions [17]. Early evidence for the amygdala’s role emerged in the context of fear, through its critical involvement in Pavlovian aversive conditioning. The basolateral amygdala, receiving afferent input from the sensory cortical areas, is essential for forming cue-outcome associations. In parallel to this, the central nucleus mediates conditioned responses via projections to midbrain and brainstem autonomic centres. The basolateral amygdala is thought to encode these associations and relay information to the central nucleus, which then initiates the appropriate behaviour and physiological responses [17, 19, 20].

Beyond aversive learning, the amygdala is a crucial component of emotional decision-making, triggering somatic states in response to primary inducers - stimuli directly experienced as pleasurable or aversive. The coupling between primary inducers and the amygdala occurs through subcortical structures such as the hypothalamus, which initiate corresponding autonomic and emotional responses [17]. In contrast, secondary inducers are stimuli generated through the recall or imagination of emotionally significant events. The ventromedial PFC is responsible for eliciting somatic responses to these secondary inducers, integrating emotional information with contextual input from memory-based systems including the dorsolateral PFC and hippocampus [17]. These structures provide essential context about the stimulus and its anticipated emotional outcome. The ventromedial PFC also connects to effector regions that induce somatic states. During decision-making, somatic responses triggered by either primary or secondary inducers generate ascending feedback signals, contributing to the conscious experience of emotion. These somatic markers subsequently bias decisions via motor effector structures such as the striatum of the basal ganglia and the anterior cingulate cortex of the PFC [17].

In addition to its role in aversive learning, the amygdala is essential for appetitive learning - a form of associative learning in which a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a rewarding or pleasant experience, promoting approach-related behaviours [21]. The central and basolateral nuclei are thought to function either in parallel or sequentially to support distinct aspects of learning. Specifically, the central nucleus mediates general, preparatory conditioning, while the basolateral nuclei contribute to value-specific conditioning [22]. Damage to the amygdala in humans is consistently associated with impaired decision-making, particularly in contexts involving risk and uncertainty. Lesions disrupt outcome representations within the ventromedial PFC, an area responsible for learning action-outcome contingencies during instrumental learning. The amygdala-medial PFC pathway is considered a critical route through which stimulus-specific outcome information is integrated with higher-order, goal-directed actions [17].

The Striatum: Motivation, Reward and Action

Economic decision-making involves selecting the most advantageous course of action by weighing the relative costs and benefits of multiple competing alternatives. This form of decision-making requires a neural system capable of several critical functions: (1) forming associations between specific actions and the anticipated value of their outcomes, (2) selecting actions while simultaneously inhibiting those deemed less favourable, and (3) dynamically adjusting behaviour in response to changing outcome values or environmental demands [23]. These processes rely on a widely distributed neural network involving cortical, limbic, and midbrain structures, with efferent projections from these regions converging in the striatum of the basal ganglia, positioning it as a central hub for integrating motivational, cognitive, and motor information [23].

The striatum serves as the primary input nucleus of the basal ganglia and forms part of multiple parallel cortico-subcortical loops. It receives glutamatergic inputs from the cortex and thalamus, alongside dense dopaminergic innervation from midbrain neurons. Through this, the striatum relays processed information back to the cortex via the thalamus, positioning it as a key integrative structure for learning and decision-making [23, 24].

Within the striatum, decision-making is mediated by two main output pathways, the direct and indirect pathways, both of which contain medium spiny neurons (MSNs). The MSNs of the direct pathway express D1-family dopamine receptors and inhibit the main output nuclei of the basal ganglia - the internal globus pallidus and substantia nigra pars reticulata - thereby promoting action initiation [24]. In contrast, MSNs of the indirect pathway express D2-family dopamine receptors, which ultimately increase basal ganglia output, suppressing competing or inappropriate actions. Classically, these pathways regulate behaviour by oppositely modulating the firing rates of basal ganglia output nuclei: activation of the direct pathway leads to disinhibition of brainstem motor structures and thalamic projections to the motor cortex, facilitating movement, while activation of the indirect pathway enhances inhibition, suppressing action execution [24].

This functional opposition extends to decision-making processes. Striatal subregions, including the dorsomedial and ventral striatum, which receive input from the PFC, differentially influence value-based decisions, while regions such as the tail of the striatum, which receive input from the sensory cortex, contribute to perceptual decisions [24]. Importantly, the dorsomedial and dorsolateral striatum have distinct roles in striatal-mediated learning. Lesions to the dorsomedial striatum impair goal-directed instrumental conditioning, while lesions to the dorsolateral striatum disrupt habit formation, indicating their respective involvement in the acquisition and consolidation phases of skill and action learning [23].

The striatum also plays a critical role in modulating goal-directed behavior through reward and aversion learning. The direct and indirect pathways contribute to the acquisition of rewarding stimuli and the avoidance of aversive stimuli, respectively. Optogenetic studies have demonstrated that the activation of direct pathway neurons within the nucleus accumbens (NAc) induces persistent reinforcement, whereas stimulation of indirect pathway neurons is sufficient to produce sustained avoidance behaviours [23, 25]. The reward-facilitating effects of the direct pathway are dependent on dopamine D1-receptor activation within the NAc, while inactivation of D2-receptors within the indirect pathway underlies passive avoidance learning [23, 26]. These findings highlight the centrality of striatal circuits in value-based decision-making, linking motivational and cognitive inputs to action selection.

Stress and Decision-Making: Emotional Influences on Choice

While delineating the neural pathways involved in decision-making provides valuable context for understanding the biological foundations of choice, it is equally important to examine how these systems are influenced by real-world factors, such as stress [27]. Stress is theorised as an adaptive evolutionary response shaped by natural selection to enhance an organism’s ability to cope with situations requiring immediate action of defence. When confronted with potential danger, the sympathetic nervous system triggers a fight-or-flight response, initiating protective responses that improve survival in adverse conditions and mitigate the harmful effects of environmental threats [27].

In contemporary contexts, however, stress is more frequently elicited by persistent, lower-intensity demands such as academic pressure, social obligations, and daily inconveniences. Under these conditions, stress can lead individuals to revert to intuitive, autonomic decision-making processes, favouring premature, habitual, or emotionally charged choices over deliberate, goal-directed actions [27]. This occurs because stress impairs PFC functions responsible for working memory, attention regulation, and cognitive flexibility, shifting decision control from a thoughtful, ‘top-down’ prefrontal system to a reactive, ‘bottom-up’ mode dominated by the amygdala and related subcortical structures [27].

Acute stress activates the locus coeruleus in the brainstem, resulting in the rapid release of norepinephrine. This enhances environmental scanning, heightens vigilance, and improves the detection of unexpected or potentially threatening stimuli [28]. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that humans exhibit increased amygdala activity immediately following stress induction, alongside enhanced functional connectivity with regions of the salience network - a system involved in autonomic-neuroendocrine control, visceral perception, and attentional regulation. As a result, stress biases individuals toward well-learned habits and routines, facilitating rapid, reflexive responses while conserving limited cognitive resources under conditions of high demand [28].

This neurochemical shift is primarily driven by increased levels of norepinephrine and dopamine, which disrupt PFC activity and enhance amygdala processing. Consequently, flexible, goal-directed decision-making is replaced by more rigid, stimulus-bound responses during initial stress reactions [28]. Once a stressor resolves, executive control processes are typically re-engaged, emotional reactivity subsides, and higher-order cognitive functions are restored. However, when sympathetic activation persists or is maladaptively regulated, it can impair an individual’s capacity to exert cognitive control over the emotional aspects of decision-making. In such cases, stress not only influences immediate behaviour but may also alter the way experiences are encoded into memory, changing the perceived significance of events and potentially shaping future decision-making strategies [28].

Dopamine and Dopaminergic Signalling: The Reward System

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter essential for regulating the brain’s reward circuitry, motivational control, and goal-directed behavior, as well as being associated with mechanisms underlying addiction and dependence. The primary sources of dopamine within the brain are the dopamine-producing neurons of the ventral midbrain, located in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) [29]. These neurons form the basis of three major dopaminergic pathways in the central nervous system: the nigrostriatal, mesolimbic, and mesocortical circuits. Among these, the mesolimbic system, often referred to as the brain’s reward pathway, encompasses interconnected brain regions responsible for processing both the physiological and cognitive aspects of reward [29, 30].

The mesolimbic pathway originates in the VTA and projects dopaminergic signals to several key brain areas, including the PFC, NAc, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, and hippocampus. Within this system, dopamine modulates distinct functions across several structures: it supports learning and memory in the hippocampus, while in the NAc or ventral striatum, it governs reward valuation, motivational drive, and the perception of pleasure [29-31]. Meanwhile, the mesocortical pathway primarily influences higher-order cognitive processing, such as decision-making, action selection, and future planning. Disruptions to dopaminergic transmission within this pathway have been associated with motivational impairments, which can be easily mistaken as apathy or laziness [29, 31]. Dopamine release via the NAc is typically triggered by the anticipation or experience of a rewarding stimulus, contributing to reinforcement learning. Additionally, the dorsal striatum plays a crucial role in selecting actions, initiating decision processes, and regulating habitual behaviours [29, 31, 32].

Research has shown that dopamine neurons responsible for encoding motivational value project to the brain regions involved in evaluating outcomes, guiding approach and avoidance behaviours, and facilitating-value based learning. Specifically, projections from the ventromedial SNpc and VTA target the ventromedial PFC, particularly the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) [29]. The OFC has consistently been implicated in value coding, through functional neuroimaging studies and electrophysiological recordings. It is thought to contribute to the evaluation of choice options, the encoding of expected outcomes, and the continual updating of these expectations through learning. Furthermore, the OFC plays a key role in processing negative prediction errors - the discrepancy between expected and actual outcome - which are particularly salient to value-coding dopamine neurons during learning [29].

The medial regions of the dopaminergic midbrain also project to the ventral striatum, including the NAc shell. Experimental evidence indicates that this region encodes the motivational value of sensory rewards, such as taste stimuli, with dopamine release into the NAc shell exerting strong reinforcing effects [29]. Conversely, a reduction in dopamine within this area has been associated with aversive responses. Importantly, distinct subregions of the NAc shell appear to specialise in controlling either appetitive or aversive behaviours, both of which depend on dopaminergic input. It is proposed that value-related signals are spatially restricted within these subregions, contributing to the precise modulation of motivational behaviours [29].

In addition, dopamine neurons originating in the SNpc extend projections to the dorsal striatum, suggesting that this region receives dopaminergic signals encoding both motivational value and the salience of stimuli [29]. These value-coding dopamine neurons are thought to deliver instructive signals to striatal circuits involved in value learning and the development of stimulus-response habits. Activation of these neurons engages the direct pathway, promoting behaviours aimed at obtaining rewards, while pauses in their activity engage the indirect pathway, facilitating the learning of avoidance behaviours in response to negative outcomes [29].

Procrastination: Self-Control Failures in Decision-Making

One particularly relatable manifestation of these neural and motivational trade-offs is procrastination. Procrastination, a behaviour familiar to many, involves the voluntary delay of an intended task despite knowing that postponement is likely to result in negative future consequences [33, 34]. This tendency often stems from the brain’s bias towards immediate gratification. When confronted with tasks perceived as effortful, tedious, or aversive, individuals frequently rely on reward-based motivators to sustain engagement. These behaviours momentarily activate the brain’s reward system, reducing avoidance tendencies by associating task completion with a pleasurable outcome [33, 34].

Research suggests that procrastination reflects a breakdown in self-regulatory processes, where individuals struggle to resist immediate temptations at the expense of long-term goals [33, 34]. Those with lower self-control capacity are more likely to favour short-term rewards, deferring tasks that require sustained effort and delaying actions that would serve future outcomes. The temporal decision model, a theoretical framework describing how individuals make choices involving outcomes at different points in time, interprets procrastination as a motivational conflict between avoidance and goal pursuit. Here, task aversiveness fuels avoidance behaviour, while anticipated incentives encourage task initiation and persistence [33, 34].

In contemporary settings, this dynamic is evident in students offering themselves small rewards - such as a sweet treat, time on social media, an episode of Netflix, or an online shopping break - to offset the discomfort of completing demanding tasks, a process linked to dopamine release within the mesolimbic reward system [33, 34]. Other commonly used motivators include messaging friends, watching YouTube clips, or going for a coffee run. Ultimately, procrastination arises from an interaction between failures of self-control and motivational trade-offs, driven by the brain’s sensitivity to immediate rewards and its tendency to devalue delayed benefits [33, 34].

Conclusion

Decision-making is shaped by a dynamic interplay between multiple brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, striatum, and dopaminergic midbrain pathways, each contributing to the evaluation, selection, and execution of actions. While these neural systems provide the biological framework for rational choice and goal-directed behaviour, they are continuously modulated by real-world factors such as stress, emotion, and habit. Stress impairs prefrontal control, favouring rapid, emotionally driven decisions, while the brain’s reward systems bias individuals toward immediate gratification, often at the expense of long-term goals. This is particularly evident in behaviours like procrastination, where motivational trade-offs and self-control failures lead to task avoidance in favour of shortterm rewards. Small incentives - such as a sweet treat, social media break, or other pleasurable activities - temporarily activate the brain’s mesolimbic reward system, offsetting task aversiveness and encouraging action. Importantly, while these mechanisms can drive unhelpful patterns of avoidance and impulsivity, the brain’s neuroplasticity offers opportunities to reshape decision-making processes over time. Through strategies that strengthen executive control, manage stress, and consciously reframe reward structures, individuals can retrain their cognitive and motivational systems, promoting more adaptive, deliberate, and goal-aligned behaviours.

Glossary

Appetitive stimulus: A stimulus that is pleasant or desirable, typically approached in decision-making.

Aversive stimulus: A stimulus that is unpleasant or undesirable, typically avoided in decision-making. Basolateral: Located at the base and side of a structure or the brain.

Dorsal: Refers to the back or upper side of a structure or the brain.

Dorsolateral: Located towards the back and sides of a structure or the brain.

Dorsomedial: Located towards the back and middle of a structure or the brain.

Instrumental learning: A type of associative learning where voluntary behaviors are shaped by their consequences, also known as operant conditioning.

Lateral: Away from the midline, towards the outer sides of a structure or the brain.

Medial: Towards the midline of a structure or the brain.

Salient, salience: The quality of a stimulus that makes it stand out or capture attention, relative to other stimuli and the surrounding environment.

Somatic markers: Physiological signals generated in response to emotional experiences that help guide decisionmaking by marking certain outcomes as positive or negative.

Ventral: Refers to the front or underside of a structure or the brain.

Ventromedial: Located towards the front and middle of a structure or the brain.

Glossary

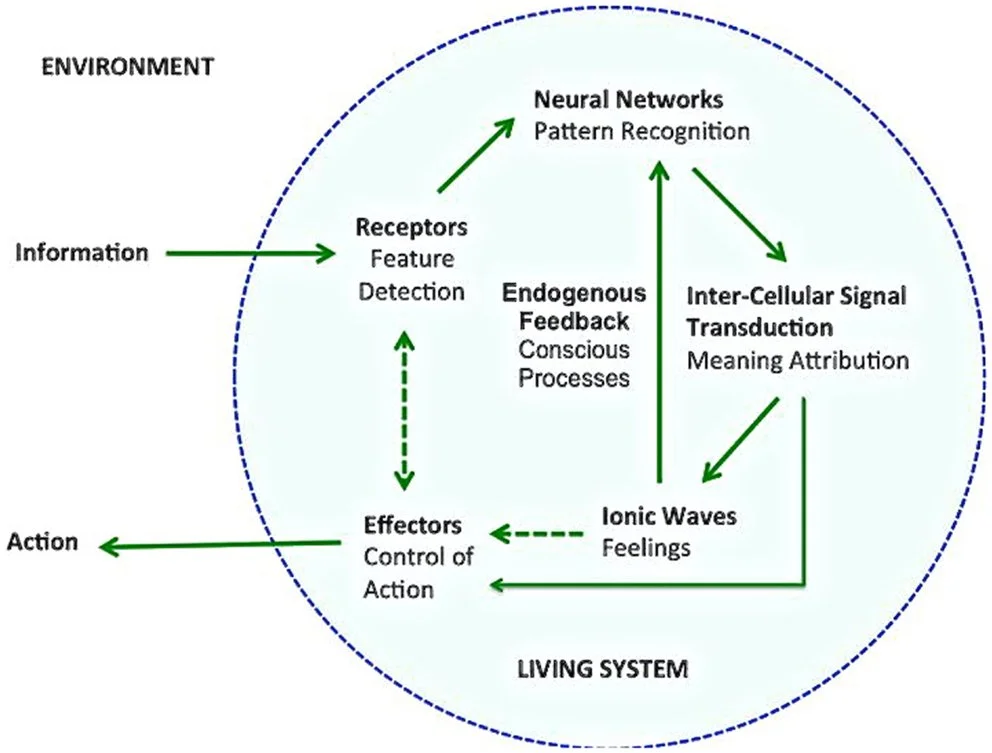

Figure 1: A diagrammatic representation of mental functioning in relation to the perception-action cycle. External information is detected, prompting a call for action. An internal process of conscious and unconscious information processing, including pattern recognition, follows. This leads to a behavioural response, the outcome of which (e.g. feelings, consequences, and benefits) is relayed back to the brain to inform future decisions [15].

The Perception-Action Cycle: Bridging Thought and Action

The PA cycle describes a circular exchange of information between an individual and their environment. As illustrated in Figure 1, environmental stimuli are detected by receptors, and this connection carries internal feedback from the receptors to effectors [3, 15]. Feedback travels via long fibre connections from the frontal cortex to the posterior cortex, gradually shifting emphasis from executive function to sensory processing. This enables anticipated feedback, which operates on the PA cycle before an action is carried out, preparing the sensory and motor systems for action and its potential consequences [3, 15].

The PFC plays a crucial role in integrating, coordinating, and directing the PA cycle. In this cycle, perception encompasses (1) the memory and knowledge that transforms sensation into perception, (2) the biological drivers influencing a person’s behaviour, and (3) the outcomes of previous decisions [3]. The mechanisms underpinning the PA cycle are involuntary and largely involve the hypothalamus and autonomic nervous system. At lower levels, the cycle governs automatic reactions such as defensive reflexes. At higher cognitive levels, these actions include decisions informed by probabilistic predictions drawn from experience, where individuals assess past outcomes and anticipated consequences to guide present choices [3]. This enables individuals to interpret visual and environmental stimuli that inform basic decision-making processes, such as distinguishing edible from inedible food, or automatically adjusting one’s grip on a coffee mug versus a wine glass [16].

[1] S. Prezenski, A. Brechmann, S. Wolff, and N. Russwinkel, “A cognitive modeling approach to strategy formation in dynamic decision making,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 8, no. AUG, 2017, doi: 10.3389/ fpsyg.2017.01335.

[2] W. Edwards, “Dynamic Decision Theory and Probabilistic Information Processings,” Human Factors: The Journal of Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, vol. 4, no. 2, 1962, doi: 10.1177/001872086200400201.

[3] J. M. Fuster, “Prefrontal cortex in decisionmaking: The perception-action cycle,” in Decision Neuroscience: An Integrative Perspective, 2017. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12- 805308-9.00008-7.

[4] Z. J. Guo, J. Chen, S. Liu, Y. Li, B. Sun, and Z. Gao, “Brain areas activated by uncertain reward-based decision-making in healthy volunteers,” Neural Regeneration Research, vol. 8, no. 35, 2013, doi: 10.3969/j. issn.1673-5374.2013.35.009.

[5] S. S. Moghadam, F. S. Khodadad, and V. Khazaeinezhad, “Review paper: An algorithmic model of decision making in the human brain,” Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 10, no. 5. 2019. doi: 10.32598/bcn.9.10.395.

[6] M. H. Rosenbloom, J. D. Schmahmann, and B. H. Price, “The functional neuroanatomy of decision-making,” Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, vol. 24, no. 3, 2012, doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11060139.

[7] S. W. Kennerley and M. E. Walton, “Decision making and reward in frontal cortex: Complementary evidence from neurophysiological and neuropsychological studies,” Behavioral Neuroscience, vol. 125, no. 3, 2011, doi: 10.1037/a0023575.

[8] S. Funahashi, “Prefrontal contribution to decision-making under free-choice conditions,” Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 11, no. JUL. 2017. doi: 10.3389/ fnins.2017.00431.

[9] A. García-Molina, “Phineas Gage and the enigma of the prefrontal cortex,” Neurología (English Edition), vol. 27, no. 6, 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2010.03.002.

[10] K. O’Driscoll and J. P. Leach, “‘No longer Gage’: an iron bar through the head,” BMJ, vol. 317, no. 7174, 1998, doi: 10.1136/ bmj.317.7174.1673a.

[11] M.-M. Mesulam, “Behavioral Neuroanatomy Large-Scale Networks, Association Cortex, Frontal Syndromes, the Limbic System, and Hemispheric Specializations,” in Principles of Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology,2023. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780195134759.003.0001.

[12] P. S. Goldman‐Rakic, “Circuitry of Primate Prefrontal Cortex and Regulation of Behavior by Representational Memory,” in Comprehensive Physiology, 1987. doi: 10.1002/cphy.cp010509.

[13] S. Funahashi, “Neuronal mechanisms of executive control by the prefrontal cortex,” Neuroscience Research, vol. 39, no. 2, 2001, doi: 10.1016/S0168-0102(00)00224-8.

[14] S. Funahashi and J. M. Andreau, “Prefrontal cortex and neural mechanisms of executive function,” Journal of Physiology Paris, vol. 107, no. 6, 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2013.05.001.

[15] A. Pereira, R. P. dos Santos, and R. F. Barros, “The calcium wave model of the perception-action cycle: Evidence from semantic relevance in memory experiments,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 4, no. MAY. 2013. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00252.

[16] P. Kirkland, G. di Caterina, J. Soraghan, and G. Matich, “Perception Understanding Action: Adding Understanding to the Perception Action Cycle With Spiking Segmentation,” Frontiers in Neurorobotics, vol. 14, 2020, doi: 10.3389/fnbot.2020.568319.

[17] R. Gupta, T. R. Koscik, A. Bechara, and D. Tranel, “The amygdala and decision-making,” Neuropsychologia, vol. 49, no. 4, 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.09.029.

[18] B. Seymour and R. Dolan, “Emotion, Decision Making, and the Amygdala,” Neuron, vol. 58, no. 5. 2008. doi: 10.1016/j. neuron.2008.05.020.

[19] LeDoux, “The amygdala and emotion: a view through fear,” in The Amygdala, 2023. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198505013.003.0007.

[20] B. S. Kapp, P. J. Whalen, W. F. Supple, and J. P. Pascoe, “Amygdaloid contributions to conditioned arousal and sensory information processing.,” in The Amygdala: Neurobiological Aspects of Emotion, Memory, and Mental Dysfunction., 1992.

[21] M. G. Baxter and E. A. Murray, “The amygdala and reward,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 3, no. 7. 2002. doi: 10.1038/nrn875.

[22] B. W. Balleine and S. Killcross, “Parallel incentive processing: an integrated view of amygdala function,” Trends in Neurosciences, vol. 29, no. 5. 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.002.

[23] T. Macpherson, M. Morita, and T. Hikida, “Striatal direct and indirect pathways control decision-making behavior,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 5, no. NOV. 2014. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01301.

[24] Cox and I. B. Witten, “Striatal circuits for reward learning and decisionmaking,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 20, no. 8. 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0189-2.

[25] A. v. Kravitz, L. D. Tye, and A. C. Kreitzer, “Distinct roles for direct and indirect pathway striatal neurons in reinforcement,” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 15, no. 6, 2012, doi: 10.1038/nn.3100.

[26] T. Hikida et al., “Pathway-specific modulation of nucleus accumbens inreward and aversive behavior via selective transmitter receptors,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 110, no. 1, 2013, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220358110.

[27] R. Yu, “Stress potentiates decision biases: A stress induced deliberation-to-intuition (SIDI) model,” Neurobiology of Stress, vol. 3. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2015.12.006.

[28] L. F. Sarmiento, P. Lopes da Cunha, S. Tabares, G. Tafet, and A. Gouveia Jr, “Decision-making under stress: A psychological and neurobiological integrative model,” Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, vol. 38, p. 100766, Jul. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2024.100766.

[29] E. S. Bromberg-Martin, M. Matsumoto, and O. Hikosaka, “Dopamine in Motivational Control: Rewarding, Aversive, and Alerting,” Neuron, vol. 68, no. 5. 2010. doi: 10.1016/j. neuron.2010.11.022.

[30] R. G. Lewis, E. Florio, D. Punzo, and E. Borrelli, “The Brain’s Reward System in Health and Disease,” in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol. 1344, 2021. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030- 81147-1_4.

[31] L. Speranza, U. di Porzio, D. Viggiano, A. de Donato, and F. Volpicelli, “Dopamine: The neuromodulator of long-term synaptic plasticity, reward and movement control,” Cells, vol. 10, no. 4. 2021. doi: 10.3390/ cells10040735.

[32] D. Woitalla et al., “Role of dopamine agonists in Parkinson’s disease therapy,” Journal of Neural Transmission, vol. 130, no. 6. 2023. doi: 10.1007/s00702-023- 02647-0.

[33] K. Gao, R. Zhang, T. Xu, F. Zhou, and T. Feng, “The effect of conscientiousness on procrastination: The interaction between the self-control and motivation neural pathways,” Human Brain Mapping, vol. 42, no. 6, 2021, doi: 10.1002/hbm.25333.

[34] P. Steel, “The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 133, no. 1. 2007. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65.

Aariana is doing her Masters in Biomedical Science this year. She’s passionate about neuroscience, neuropsychology, and exploring how brain biology shapes human behaviour. Outside of university, she can usually be found curled up with a good book.