Mushrooms, Memory and Modernity: The Unseen Value of Scientific Collections

Collections Management and Mycology | Dylan Ramdin

Herbaria and similar scientific collections are some of our most overlooked and underappreciated scientific assets. In Aotearoa, New Zealand there are a number of Nationally Significant Collections and Databases (NSCDs) which hold preserved specimens of our native biodiversity and environmental taonga, both past and present, for use in research and study. One such collection that I had the privilege of getting to know over the summer of 2024-25 was The New Zealand Fungarium - Te Kohinga Hekaheka o Aotearoa, Plant Disease Division (PDD), which is operated by the Crown Research Institute Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research (MWLR). This collection and its accompanying digitized portal contains over 120,000 dried specimens and 3000 types representing the fungal diversity of NZ and other localities [1].

The specimens are carefully stored at 15 C° in archival packets and boxes in rows of lockers and sliding cabinets in a massive concrete PC2 vault facility, and serve a myriad of uses. One such use is as a research aid on plant pathology; providing physical specimens whose characters can still be examined decades after drying. This allows us to identify and study devastating plant pathogens such as those which cause Myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) and Kauri Dieback (Phytophthora agathidicida), or those which may pose a new risk to biosecurity.

More obvious is the Fungarium’s use as a repository and informal time-series of the fungal ecology of Aotearoa New Zealand; seeing which specimens are occurring where, as different substrates fall under examination over time. It is this role which might be interesting to most, enamoured as we have all become with toadstools and puffballs. Many of Aotearoa New Zealand’s charismatic mushroom forming genera, such as the bright blue Werewere-kokako (Entoloma hochsteterii), are stored, studied and described by the team at the PDD Fungarium in co-operation with overseas researchers and domestic experts both amateur and professional.

Along with the International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants (ICMP), the Fungarium also acts as a genetic resource to advance our understanding of systematics and phylogeny. The genomes of the specimens present can be sequenced, and made available to international researchers interested in the genetics and biochemistry of fungi. Even its role as a protective treasure chest is vital, preserving rare and notable specimens which the average person would only be very lucky to discover, or which no longer exist in the wild. It should be apparent the value that collections like this and others in Aotearoa New Zealand hold.

Despite that value, to outside observers herbaria (and fungaria) and other collections can seem anachronistic. Large and expensive physical artifacts much like a museum collection, but even less profitable. Indeed, the PDD Fungarium possesses many mementos of older days. 100-year-old specimens crowded in fading yellow packets, a wall of physical journal separates from the era when it was necessary to send to Wellington or England for the exact pages you needed, and boxes of research materials on metal shelves from decades ago that have not had eyes laid on them since they were first packed away. This air of age hangs heavy when considering the wider closure of so many collections across the world (over 100 in the USA alone since 1997), the most recent and one of the most significant of which being that of the Duke University herbarium, announced in 2024 [2], [3].

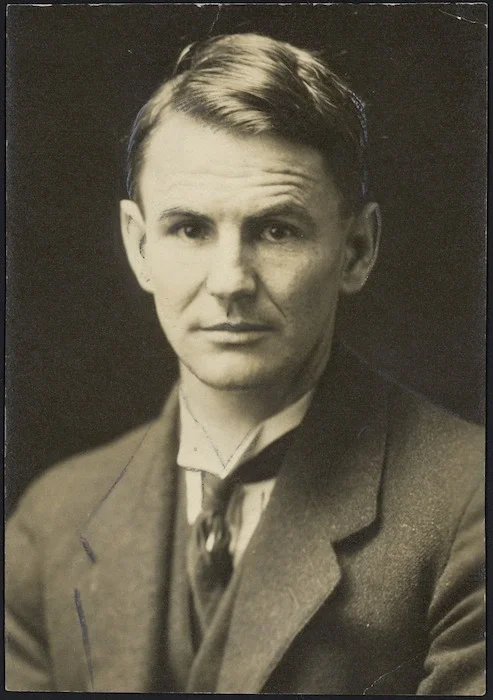

Figure 2: G.H. Cunningham, founder of the New Zealand Fungarium and the “Father of New zealand Mycology”. Attribution: Alexander Turnbull Library, Dominion Post Collection.

It can be hard to justify the cost, work and space of a collection like the PDD Fungarium. This is especially true when the organizations in which they reside press into even more expensive and “cutting-edge” forays with genetics and AI which might necessitate $60k DNA extraction robots to pursue (as is the case with MWLR). Science can often be pushed to neglect the past, either by its internal adherents enamored by new breakthroughs or by external pressures, to rationalize, produce and adapt. However, in addition to the tangible benefits of these collections I have listed above, I would also like to propose some less obvious and more esoteric benefits to collections that we as scientists would be wise to consider more seriously.

Within The Vault of the PDD Fungarium the tendency to tunnel vision on what might be on the horizon is muted. You are constantly interacting not only with specimens of the past (the oldest of which dates back to 1840), but also with the contexts which produced them. You see how the collection grows in relation to the interests and specialties of the people who tend them [1]. In that way the vault is an expression of how science is not unbiased and cold, but instead messy and warmed and directed by the passions and proclivities of its caretakers.

The PDD Fungarium has had four curators since its inception. Starting with Gordon Heriot Cunningham who began the collection as a personal herbarium while employed with the Department of Agriculture in 1918, and then formalized it when the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) was created in 1936[4]. Joan Dingley followed him, and from 1962 to 1976 played a massive role in dramatically expanding the fungarium and expanding knowledge of plant pathology to the public [5]. From 1976 to 2008, Eric McKenzie helped push the Fungarium to international standards especially through his and the rest of the PDD’s work in Pacific agriculture [6]. Since 2008, the Fungarium has been curated by Mahajabeen Padamsee, under whom the push to modernize, digitize and begin the heavy work of sequencing specimens has taken place alongside flagship projects like “Beyond Myrtle Rust” [8].

Each of these mycologists also had clear focuses, reflected in the accessions that bear their collector titles and the species that hold them as descriptive authorities. Cunningham with his polypores (bracket fungi), Dingley with her ascomycetes (sac fungi) and hypocreales, and both McKenzie and Padamsee with rust fungi and puccinia. In addition to the curators, the Fungarium has played host to numerous experts in their particular genera. This includes Greta Stevenson and Marie Taylor, two giants in NZ agarics, and even foreign mycological greats such as Egon Horak and Franz Petrak. To non-mycologists these names are utterly inconsequential, but specialists in the field can appreciate the acclaim. Herbaria as a scientific endeavor therefore have immense power as entities allowed to persist through long periods of time, while benefiting from the influence of such varied individuals.

Figure 3: The present team (and associated summer interns) of the New Zealand Fungarium, Plant Disease Division, and International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants. Attribution: Dr. PK Buchanan (2024).

Simultaneously, the PDD Fungarium also displays the ways in which science is constantly in dialogue with the context and conditions under which it operates. The PDD has been changed and challenged as it has passed hands over its lifespan, from Cunningham’s initial collection through the DSIR years and MWLR. Now, as a part of the coalition government’s reforms to the science system, The Fungarium will likely have a new steward in the form of whichever public research institution takes up the “bioeconomy” portfolio in the coming months and years. Each of these shifts has involved massive changes in priority and administration, not the least of which being an increasing shift in focus to a profit-incentive model with greater emphasis put on rationalisation and commercial applications. However, concomitant with that change has been an increased importance placed on the role of the Fungarium; with it going from being just a small segment of a centralized research institute to a major chunk of a smaller, disconnected organization with wider influence in biosecurity and bioindustrial projects. Nonetheless, these changes result in projects being dropped, people being reclassified and the work of good science being made more difficult through new financial pressures. There is a constant game of justification for the continued maintenance of these scientific collections, and a pattern of trying to convince present-minded (read: short-sighted) managerial and political appointments of their worth.

Despite this, there is continuity embodied by the institutional knowledge of its members and employees. People who have stood with the Fungarium and can remember how things used to be done whether good or bad; more or less efficient. Memory. People. He Tangata. As much as the PDD Fungarium and scientific collections are a preservation of our biota and fungal taonga it is also a repository of human interest. That human element is contained within the work of the Fungarium and the personalities of those who have contributed to it, both in an abstract sense and in the form of artifacts, specimens, notes and remnants left behind. Even more poignant is the way that among the blurring, indistinct names of taxa there are whole genera named in loving memory of the departed who, through their work at institutions dedicated to these collections, have made an indelible impact on the field. Dingleya, Rossbeevera, multiple genera with a species named ‘cunninghamii’. Collectors who spent their lives preserving these species for posterity and research, then being preserved in some form themselves. In that remembering, and the constant interplay between past and present, we can protect a hope that things have not always been as they are. All eras are as fleeting as fruiting bodies after the rainfall, and ironically, their preservation can help us to remember that.

Figure 1: The historic display case in the Vault of the New Zealand Fungarium. It contains several notable specimens often used in tours and demonstrations, as well as memorabilia dedicated to two previous curators GH Cunningham and Joan Dingley. Attribution: Manaaki Whenua - Landcare research.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to give thanks to my primary supervisors over the course of the Summer internship, Maj Padamsee and Adrienne Stanton who, in addition to granting ample work, were kind, patient and engaging tea-time companions. Thanks to Peter Johnston, Peter Buchanan, Duckchul Park and the whole team at the PDD fungarium and systematics team for sharing their ample passion for their areas of study and rich stories accumulated over long years of experience. And thanks to the whole team at MWLR Tamaki for allowing us interns to integrate so seamlessly into every day operations and special farewell lunches.

[1] Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. “About the NZ Fungarium.” landcareresearch.co.nz. Accessed: Feb 27th 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/tools-and-resources/ collections/new-zealand-fungarium-pdd-te-kohinga-hekaheka-oaotearoa/about-the-nz-fungarium/

[2] B. Deng. “Plant collections left in the cold by cuts.” Nature, vol. 523, no. 7558, p16. Jul. 2015, doi: 10.1038/523016a

[3] C. Zimmer, (Feb 21, 2024) “Duke Shuts Down Huge Plant Collection, Causing Scientific Uproar.” The New York Times. Feb. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/21/science/ duke-herbarium.html (Accessed: Jan 20th 2025)

[4] J. M. Dingley, “Cunningham, Gordon Herriot.” Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/ biographies/4c47/cunningham-gordonherriot (accessed 27 February 2025)

[5] K. Hannah, “Dingley, Joan Marjorie.” Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 2022. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https:// teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/6d7/ dingley-joan-marjorie

[6] M. Stadler, and K.D. Hyde, “Special issue dedicated to Dr Eric McKenzie to celebrate his 70th birthday.” Mycol Progress, vol. 16, pp. 269–270, Apr. 2017, doi: 0.1007/ s11557-017-1287-z

[7] Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research “Our People- Mahajabeen Padamsee.” landcareresearch.co.nz. Accessed: Feb. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www. landcareresearch.co.nz/about-us/ourpeople/mahajabeen-padamsee

Dylan is an aspiring academic and bodybuilder pursuing an honours in sociology, and is also a certified personal trainer. He has an interest in the social construction of science and biodiversity, and desires to synthesize social and ecological sciences to create better environmental systems and policies.