We are Living in a Material World; Save it with Knit and a Purl

Fibre Crafts and Sustainability | Lucy Schultz

The Complex Systems of Fibre-Making and the Environment

Somewhere, there is a sweater. Hand-knit from local wool, dyed with onion skins, and passed down through generations. Its cuffs are worn thin, one button hangs loose, and a single skipped stitch marks the moment the knitter’s hand faltered. You could say it’s imperfect. Or you could say it’s alive, a record of choices.

Fibre work like this is often mistaken for just a hobby, a slow pastime unsuited to modern life. Yet spinning, weaving, and knitting are among humanity’s oldest and most intricate material knowledge systems. They are not simply ways to make fabric; they form a fibre-based epistemology, inseparable from ecology, engineering, and culture. As with any complex adaptive system, fibre knowledge cannot be understood by isolating its parts. The value of a hand-made garment is not reducible to the tools or fibres that created it. Rather, it emerges from the tacit knowledge exchanged between hands, intergenerational teaching, and the environmental contexts in which those materials are grown and gathered.

Historically, these systems were everywhere. They set agricultural calendars with sheep shorn in spring [1] and mapped famous trade routes such as the Silk Road, defining global relationships [2]. They bound cultures through skill-sharing, producing textiles that were slow, intentional, and embedded in place. Every thread was part of a feedback system where material, environment, and culture co-evolved.

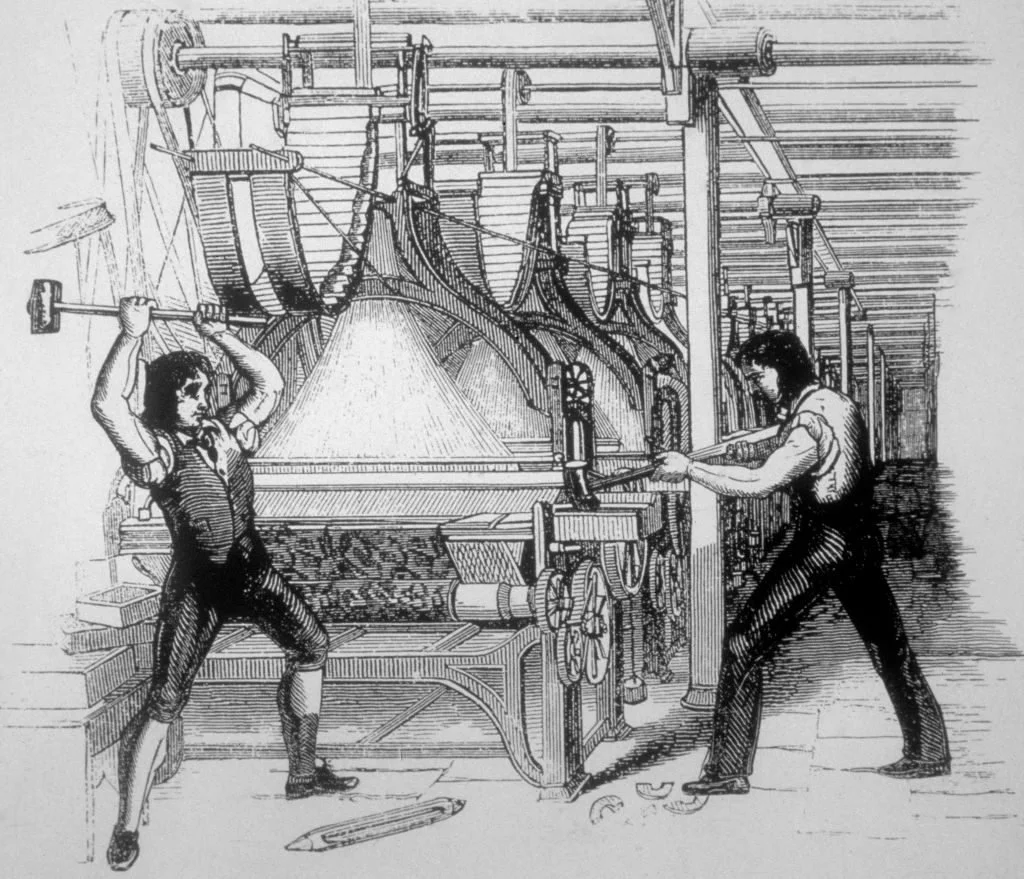

In 1826, the power loom was introduced, leaving half the weaving workforce unemployed while those still at work earned in a week what once had been a day’s pay [3]. Hunger and protest were inevitable, and the riots reflected not just anger at machines, but grief at the destruction of an entire way of life. Fibre knowledge, which had long balanced ecology, skill, and labour, was being subordinated to the speed of industrial capitalism. The loom itself was not the enemy, it was the severing of people from the land that had once fed and clothed them. The introduction of the power-loom shows that what we now call “fast fashion” did not appear overnight, rather it was built on centuries of displacing material cultures.

Machines now spin yarn faster than hands can move, factories replace workshops, and synthetic fibres untether textiles from their landscapes. Fast fashion is not only a material disruption but also a cultural amnesia. It produces clothes that are rootless, lifeless, designed to be worn briefly, then discarded. The crisis is not only waste or emissions, but the erasure of a worldview that once valued limits, reciprocity, and care. To grasp what has been lost, and what could be regained, we must recognise fibre skills not as hobbies, but as living systems whose logic still matters. They offer more than sustainable alternatives: they invite us to rethink our entire relationship with material culture. This article draws on systems thinking, historical examples, and ecological reflection to suggest that complexity is not only found in data but also in the soft systems we wear, pass down, and might once again use to guide our response to the climate crisis.

Fibre Skills as Complex Knowledge Systems

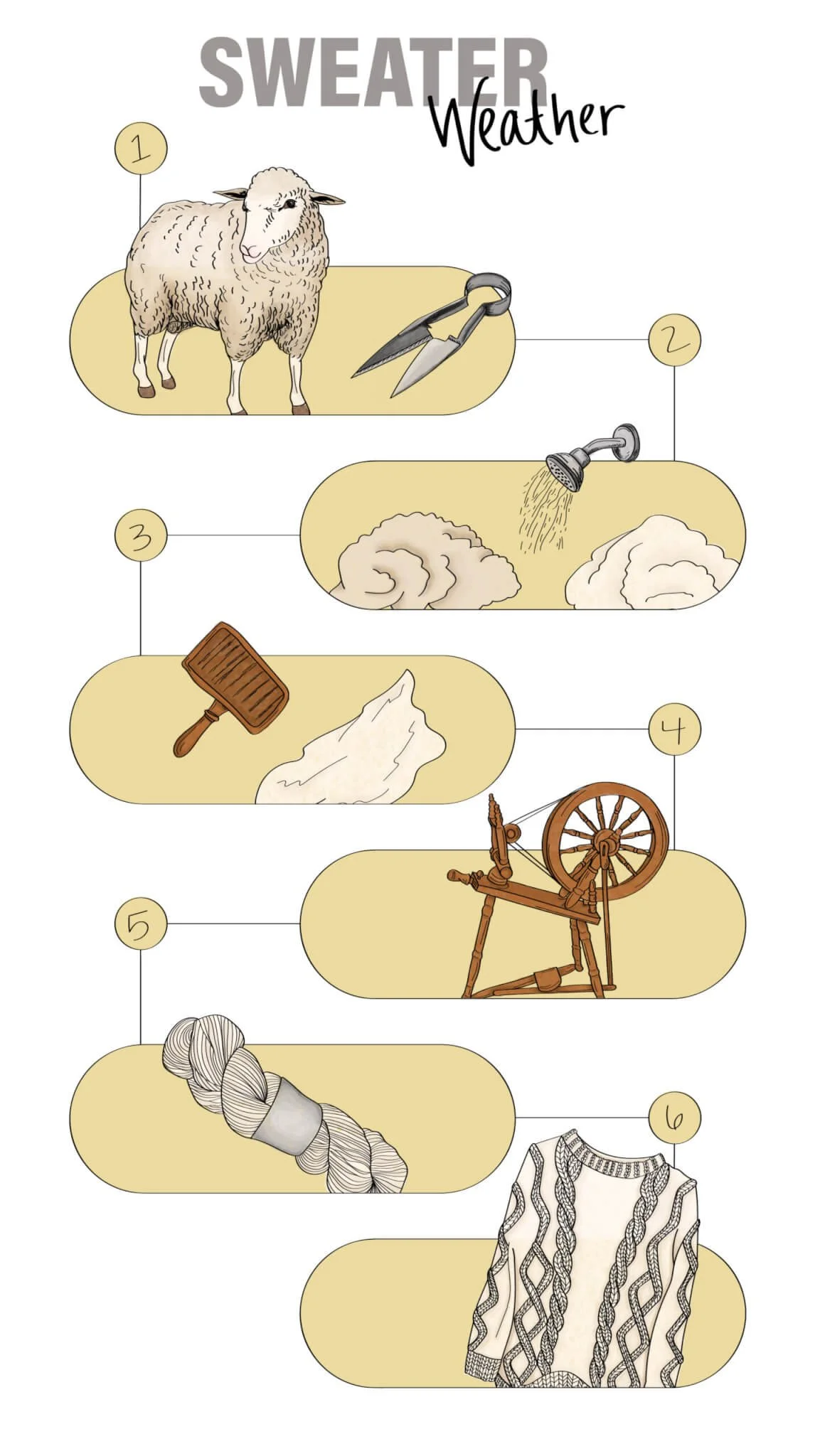

Fibre does not become a garment by accident. It emerges through a choreography of observation, intuition, and refinement. The process begins with raw fibre, a greasy fleece, or fibrous harakeke/flax. Each type requires a different approach, cleaning, separating, and preparing in ways specific to its structure and environment.

Spinning then transforms fibre into yarn, but even here there is no fixed formula. Springy merino, slippery alpaca, and wiry hemp each behave differently in the hand [5]. The spinner must judge how much twist will hold the fibres together without stiffness, and how to balance strength with softness. These decisions are not written instructions but tacit knowledge learned through repetition, failure, and feedback between hand and material. Yarn, once made, remains a system in flux. It stretches, contracts, and curls in response to tension, humidity, and temperature [5]. This is why swatching and blocking are not formalities but predictive experiments, like a litmus test of how the final product will be. Every choice, from fibre type to stitch pattern, is a variable. Adjust one, and the outcome shifts. A knitted sock that doesn’t quite fit is not just a mistake, but a demonstration of the system’s complexity and sensitivity to small changes—the butterfly effect of fibre work.

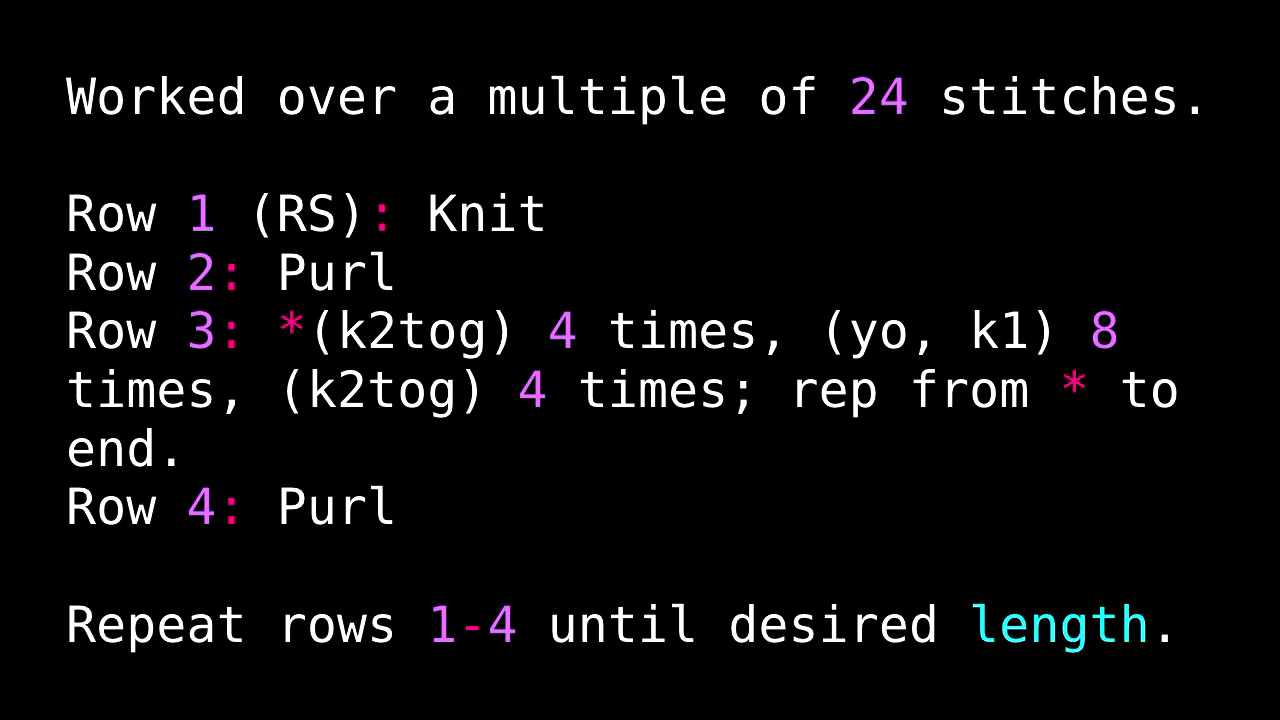

Each decision is experimental; each experiment reshapes the system. These are feedback loops made tangible, subtleties no machine can fully replicate. Scientists might call this sensitivity to initial conditions. Fibre artists call it the feel of it. Then comes another layer of complexity: the pattern. To the untrained eye, a knitting pattern might appear as an encrypted message: K2, M1R, YO, P2. To a practised knitter, it is fluent syntax, a compact language that encodes spatial logic and structural intention. Each symbol is a command; each row is a line of code. The knitter holds multiple layers of abstraction at once: the pattern on the page, the stitches in hand, and the imagined garment that will eventually emerge. This capacity to work with layers of knowledge and predictions simultaneously is a defining feature of this complex system.

Figure 2: A step-by-step illustration of traditional wool processing, from shearing and washing the fleece, to carding, spinning, and finally producing yarn. [6]

Fibre Knowledge Distribution

A pattern is transmissible across hands and generations. For most of history, this knowledge lived in bodies, gatherings, and in unrecorded practice [8]. Skills were passed on through apprenticeship and whānau.

In Aotearoa, Māori whatu (finger-weaving) demonstrates complex systems thinking in action. It carries whakapapa, seasonal rhythms, and tikanga as relational knowledge systems of environmental and cultural care. The harvesting of harakeke follows strict ecological guidelines (e.g., leaving the central shoot, or rito, intact to sustain the plant), demonstrating built-in feedback loops between human use and environmental regeneration [9]. Whatu is not just an art form, then, but an adaptive system of cultural resilience.

Across the world in Shetland, the islands’ hardy sheep and their exceptionally soft, fine wool gave rise to lace knitting as an expression of survival, trade, and identity in a harsh climate [11]. Such traditions are epistemologies in their own right, grounded in land, language, and responsibility, and shaped by distributed systems of kinship and ecology. Today, that transmission continues not just through local communities, but across digital platforms like Ravelry, where millions of knitters, spinners, and weavers exchange patterns, offer advice, and adapt designs in real time [12]. These are not just hobbyist forums, but are decentralised systems of collective intelligence. A single uploaded pattern can evolve and proliferate into hundreds of variations. What emerges is something that exceeds any single contribution.

Yet even as these knowledge systems evolve, they do so under increasing pressure. The conditions that once sustained fibre art, such as time, care, attention, and ecological connection, are being steadily eroded by the forces of speed, scale, and disposability

Figure 5: Visualisation showing the release of microplastic fibres from synthetic clothing during everyday household washing. [16]

Figure 1: An 1810s engraving of the Luddite movement, where skilled weavers resisted the industrial power loom and the collapse of their livelihoods [4].

Figure 4: A harakeke/flax plant, central to Māori weaving traditions. Harvesting follows strict ecological tikanga to ensure the plant’s regeneration and survival. [10]

System Under Threat: Fashion’s Ecological Collapse

Beneath every piece of fabric we touch lies a system older than any industry, one that once connected human hands, natural resources, and community. For most of history, textiles were woven directly into the land’s cycles where sheep grazed nearby, and where rivers cleaned and softened the fibre. This intimacy with materials meant people understood their value. Now, that connection is gone.

In its place stands an industry that hides exploitation behind fluorescent shopfronts and seasonal trends. Synthetic fibres now dominate the global market. Polyester, nylon, and acrylic— derived from fossil fuels—account for more than 60% of textiles produced worldwide [13]. These try to mimic wool or silk at a fraction of the cost, but every wash releases millions of microplastics into waterways. A single polyester fleece jacket can shed over 250,000 synthetic microfibres per wash cycle, infiltrating food chains from plankton to humans [14]. Landfills swell with discarded garments, less than 1% of which are recycled back into textiles [15].

When we view this from a complex systems perspective, we see that fast fashion is a tightly coupled, opaque global network with dangerous feedback loops: overproduction drives overconsumption, which drives waste, which demands more production. Every $5 T-shirt or “last chance” sale contributes to this harm, but the system is designed to obscure it, hiding the true cost behind a price tag [17].

The cultural costs mirror the ecological collapse. When garments are produced to be worn seven times on average before disposal, repair skills become irrelevant [18]. Knitting, mending, and weaving, once intergenerational knowledge, are given the status of hobbies rather than powerful knowledge. This cultural amnesia is precisely what allows the cycle to accelerate: without memory of slower, place-rooted systems, we become passive consumers in a disposable world. The collapse is not sudden but a slow unravelling, thread by thread. Just as ecological tipping points are reached when feedback loops break, cultural tipping points are reached when knowledge ceases to be lived. To sever slowness from fibre is to sever resilience itself.

What This Complex System Can Teach Us

And yet, the knowledge survives. It flows through rural co-ops, urban knitting circles, and massive digital platforms like Ravelry. Here, as in oral tradition, knowledge is cumulative and alive.

This complex system that blends digital and traditional practice could be a lifeline, but only if we recognise it for what it is: a resilient, decentralised, open-source model of material culture—one that contrasts sharply with the top-down, disposable logic of fast fashion. Reconnecting with textiles is not about romanticising the past or rejecting all modern production. It is about regaining agency. Learning to knit, weave, or sew is an act of resistance, a way to step out of the passive role of consumer and into an active relationship with materials.

It is about understanding the true cost of what we wear and refusing to participate blindly in a system that depletes the world it draws from. Relearning these ways of working is not nostalgic; it is strategic. By recognising fibre technology as a model of complex adaptive systems, we gain tools to rethink sustainability and education. By integrating fibre crafts into climate education as living models of interconnected systems, and by supporting repair workshops and local hubs of renewal, we can reframe textiles not just as products, but as catalysts for resilient local economies and cultural regeneration. At stake is agency. To knit or weave today is not just to make a garment but to reassert participation in material culture, and is an act of rebellion. It is to resist being a passive consumer in a system that thrives on opacity. A hand-knit sweater cannot be “fast” or “disposable”. It demands attention, repair, and relationship. That slowness is itself a radical intervention into a culture of speed.

Conclusion: Reweaving the Future

The article began with a sweater. Imperfect, hand-made, alive with the choices of its maker. Revisited now, it is more than an heirloom. It is evidence of a worldview that once linked fibre to field, craft to ecology, making to memory. If this knowledge unravels completely, we lose more than skills. We lose a model of how to live within limits, how to embed care and reciprocity in material culture, how to see complexity as something to work with rather than eliminate. The ecological crisis of fashion is not simply that we produce too much, but that we have forgotten how to produce wisely.

Yet the threads remain. From ancestral weaving traditions to global digital communities of knitters, fibre knowledge persists as a decentralised, adaptive network. As systems theory reminds us, resilience lies not in erasing complexity but in engaging with it: feedback loops, distributed intelligence, and adaptive practices are precisely what allow systems to survive change. Fibre arts teach us that sustainable systems are not just about “green” materials or recycling; they are about how we think, adapt, and stay in relationship with our resources.

In a culture that prizes speed and abstraction, these slow, intricate ways of knowing can feel radical. They remind us that complexity is not an obstacle to be simplified away, but a richness to be worked with. If we keep it, teach it, value it, and adapt it, we gain more than garments. We gain a living model for how to repair the rupture between human culture and the living world. And we will find, in each twist of fibre and each imperfect stitch, a thread leading us back. So resist that $5 shirt, rebel against the latest trend, rage against the machine, and learn to knit!

Figure 3: A presentation slide exploring parallels between knitting patterns and computer code, highlighting fibre craft as a system of logic and design. [7]

[1] R. Hartman. “The Medieval Agricultural Year.” Strange Horizons. Feb. 12. 2001. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: http:// strangehorizons.com/wordpress/non-fiction/articles/the-medievalagricultural-year/.

[2] R. Kurin. “The Silk Road: Connecting People And Cultures.” Smithsonian Folklife Festival. Accessed: 17th. August, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://festival.si.edu/2002/the-silk-road/the-silk-roadconnecting-peoples-and-cultures/smithsonian.

[3] Weavers Uprising Bicentennial Committee. “History of the 1826 uprising,” Weavers Uprising, 2024. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.weavers-uprising.org.uk/uprisinghistory/

[4] BBC History Revealed. “Your guide to the Luddite movement.” History Extra. May 11, 2020. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.historyextra.com/period/industrial-revolution/whowere-luddites-facts-what-happened/.

[5] K. Crane. “A Closer Look At Natural Fibers & Materials.” Design Pool. May 25, 2020. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.designpoolpatterns.com/a-look-at-natural-fibersmaterials/.

[6] E. E. Ambrose and L. Coghlan. “Untangling Indiana’s wool industry: A snapshot of Hoosier sheep farming.” Purdue University. Dec. 20, 2020. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https:// ag.purdue.edu/news/2020/12/untangling-indianas-wool-industry. html.

[7] K. Howard. “Knit One, Compute One.” Open Transcripts. Jan. 16, 2017. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: http:// opentranscripts.org/transcript/knit-one-compute-one/.

[8] C. E. S. Ebert, M. E. Harlow, L. Bjerregaard, and E. B. A. Strand, Traditional Textile Craft – an Intangible Cultural Heritage? Copenhagen, Denmark: Centre for Textile Research, 2016. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://ctr. hum.ku.dk/conferences/2014/E-Book_ Traditional_textile_crafts.pdf.

[9] N. Swarbrick. “Flax And Flax Working.” Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Mar. 1, 2009. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://teara.govt. nz/en/flax-and-flax-working.

[10] Christchurch City Libraries Ngā Kete Wānanga o Ōtautahi. “Harakeke.” christchurchcitylibraries.com. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/ harakeke/.

[11] E. Gordon. “The Story Of How Shetland Wool Became World Famous.” Shetland. org. Sept. 21, 2023. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https:// www.shetland.org/blog/story-shetlandwool-textiles.

[12] Ravelry. “About Ravelry.” ravelry.com. Accessed: 17th. August, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ravelry.com/about.

[13] K. Horvath. “Most Of Our Clothes Are Made From Fossil Fuels: Here’s Why That’s A Problem.” PIRG. Feb. 12, 2024. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://pirg.org/articles/most-of-ourclothes-are-made-from-fossil-fuelsheres-why-thats-a-problem/.

[14] C. O’Loughlin, “The impact of activewear/ swimwear laundering: Investigating microplastic-fibre emissions from recycled and non-recycled synthetic textiles,” J. Home Econ. Inst. Aust., vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 2–12, Jan. 2018. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https:// search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/ ielapa.107251401188651.

[15] T. Wagaw and K. M. Babu, “Textile Waste Recycling: A Need for a Stringent Paradigm Shift,” AATCC J. Res., vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 376–385, Nov.–Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1177/24723444231188342.

[16] S. H. Akyildiz et al., “Release of microplastic fibers from synthetic textiles during household washing,” Environ. Pollut., vol.357, p. 124455, Sept. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124455. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/ pii/S0269749124011692.

[17] L. Tonti. “It’s The Industry’s Dirty Secret: Why Fashion’s Oversupply Problem Is An Environmental Disaster.” The Guardian. Jan. 18, 2024. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www. theguardian.com/fashion/2024/jan/18/its-the-industrys-dirtysecret-why-fashions-oversupply-problem-is-an-environmentaldisaster.

[18] M. Igini. “10 Concerning Fast Fashion Waste Statistics.” Earth.org. Aug. 21, 2023. Accessed: 17th. August, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://earth.org/statistics-about-fast-fashion-waste/.

Lucy is a biology student at the University of Auckland specialising in biochemistry and molecular biology. Alongside her scientific studies, she is deeply engaged in fibre technologies and communities, blending a passion for making with an interest in the molecular and cultural systems that shape everyday life.