Seas of Opportunity: Marine Protected Areas for People and the Planet

Marine Protected Areas and Conservation | UoA Marine Science Society

Introduction

Marine protected areas (MPAs) play a critical role in conserving marine ecosystems, preserving biodiversity, and reducing anthropogenic effects. MPAs are a widely used marine conservation tool, which may offer full or partial protection from direct human impacts such as fishing, habitat degradation, and pollution [1], [2]. Over time, the implementation and use of MPAs has adapted, with varying levels of protection, management strategies, and conservation objectives depending on the location, including the use of Indigenous knowledge [3]. The term MPAs can be used quite broadly and may have different definitions across the world, with this article focusing on MPAs in the context of Aotearoa New Zealand. MPAs refer to any form of marine protection, including but not limited to rāhui, mataitai, and marine reserves.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, marine reserves (also known as type 1 MPAs) provide the highest level of marine protection, with a full no-take policy. The oldest marine reserve in Aotearoa, having recently turned 50 years old, is the Cape Rodney-Okakari Point Marine Reserve (Goat Island). Also known as Te Hāwere-a-Maki, it is located adjacent to the Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland Leigh Marine Laboratory and was established to preserve marine life for scientific study [3]. Since establishment, the marine reserve has offered many benefits associated with conservation, education, recreation and management, the fisheries sector, tourism, and coastal planning [4].

MPAs have many impacts on the ecosystem, affecting both wildlife and humans who rely on the moana for the air we breathe, kai, recreation, and climate regulation. This article outlines what MPAs do in a broader perspective in relation to their history and legislation and the ecological and fisheries perspectives, as well as their social, anthropogenic impact.

Legislation

The Marine Reserves Act 1971 [5] outlines Aotearoa New Zealand’s MPA policy to protect our unique marine biodiversity. This legislation aims to create a network of MPAs that represent the variety of marine habitats and ecosystems that can be found within our waters [5], [6].

There are two types of protected areas, marine reserves and MPAs, each having rules related to fishing activities within their boundaries (‘no-take’ areas versus those that allow but restrict fishing). Under the Marine Reserve Act, each MPA was created to maintain or facilitate the recovery of marine areas to support trophic linkages between ecological areas with unique species composition. The classification system for determining MPAs has evolved as science has informed policy. The Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy 2020 [7] contains marine and coastal guidance for selecting MPAs. The first strategy is representativeness, or the selection of areas that represent one or more marine habitats and ecosystem types that are unique to Aotearoa New Zealand. The second is rarity, emphasising the national or international importance of a distinct marine habitat or ecosystem. These areas are typically classified as marine reserves rather than MPAs [5], [7].

Ecological Benefits

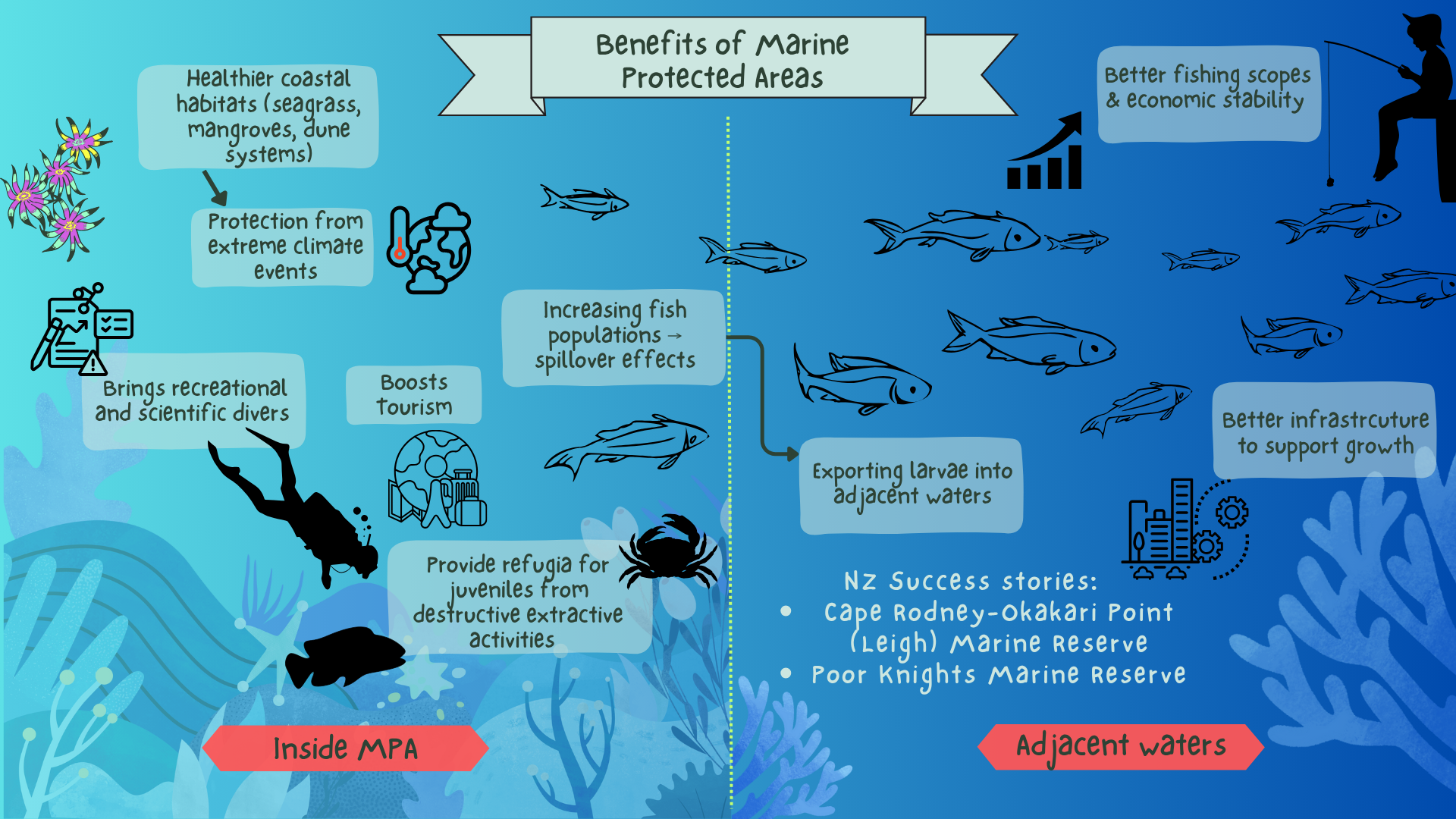

MPAs play a critical role in restoring the marine environment, enhancing biodiversity and species abundance, and promoting the growth of larger, more mature, and fecund (greater reproductive output) individuals within reserve boundaries. They also work to protect critical breeding habitats and vulnerable ecosystems, as well as support ecosystem services that contribute to the overall functioning and resilience of ecological communities.

MPAs reduce or entirely eliminate human disturbance, creating legally protected refuges where fauna and flora can recover, reproduce, and thrive undisturbed. After the Leigh Marine Reserve was established in 1975, the abundance of previously exploited (commercially and recreationally) and keystone species such as snapper (Pagrus auratus) reportedly increased up to 27 times, with rock lobster (Jasus edwardsii) increasing up to five times inside the reserve boundaries [8], [9]. Further increases included butterfish (Odax pullus), John Dory (Zeus faber), banded wrasse (Notolabrus fucicola), parore (Girella tricuspidata), blue cod (Parapercis colias), and silver drummer (Kyphosus sydenyanus)—all of which are commercially and/ or recreationally valuable [10]. Due to the absence of and protection from harmful human activities (namely fishing), MPAs cultivate distinct and biodiverse community assemblages that can be more resilient to external pressures (e.g. climate change) and support ecosystem complexity. MPAs also promote higher species abundances and trophic links compared to adjacent fished areas, reflecting the natural state of marine ecosystems prior to human interference [8], [10], [11].

By increasing survival rates, MPAs also support life history characteristics such as growth and reproduction. Species within reserve boundaries can grow larger and thus increase their reproductive output with less or no fishing pressure. This allows species to live longer, grow larger, and reach sexual maturity [12]. For example, snapper within the Leigh Marine Reserve were found to be 5.75 to 8.70 times larger in size and produce up to 19 times more eggs than snapper in adjacent fishable areas [13], [14], [15]. Additionally, snapper within MPAs are believed to produce higher-quality eggs due to having a broader diet that better supports reproductive activity; adults are larger and can therefore exploit a range of different-sized prey otherwise unavailable to smaller individuals [16], [17]. For example, only large mature adult snapper are capable of cracking open and consuming kina (Evechinus chloroticus) due to their larger and stronger jaws [18]. MPAs therefore support stock stabilisation and recruitment, providing sanctuaries for larger species more targeted by fishing activity to breed, produce spawning biomass, and balance the ecosystem by regulating prey densities.

MPAs can enhance ecosystem services (the benefits we receive directly or indirectly from the environment), inviting reflection on our intrinsic connection to nature [11], [19]. Ecosystem services are broadly classified into three main categories: provisioning, regulating, and cultural. Provisioning services, such as food or raw materials (e.g. seaweed, algae), are obtained from ecosystems, while regulating services are the benefits derived from the regulation of natural ecosystem processes. This can contribute to collective ecosystem function, such as nutrient recycling. Lastly, cultural services are the non-material benefits provided by ecosystems, from spiritual heritage to leisure and recreation [20]. MPAs enhance ecosystem services, as the protection of vulnerable and ecologically or culturally valued ecosystems (determined by iwi and the Department of Conservation) promotes their recovery and revitalisation, leading to a cascade of positive impacts. For example, MPAs contribute to food provisioning by creating spill-over effects, whereby juvenile fish—lacking swimming ability—drift with ocean currents to far beyond the protective bounds of their MPA natal site [21]. This passive movement of juveniles restores fisheries in areas fishable to the public and industry by enhancing local recruitment, with 11% of juvenile snapper up to 40 km away from the Leigh Marine Reserve found to be the offspring of its spawning adults [21]. MPAs are also recognised for the regulating services they provide, chief among them climate and nutrient regulation (carbon sequestration), greater water quality and clarity, and increased productivity and habitat provisioning, all of which can be provided by seaweed and kelp forests. Following the establishment of the Leigh Marine Reserve, kelp forest habitats regenerated, providing habitats and nurseries for juveniles, as well as protection from predators within the three dimensional structures [22]. Notably, reserve productivity increased by a significant 60%, as kelp forests absorb and fix atmospheric carbon via photosynthesis, creating organic compounds/energy and fuelling the productivity that feeds into the wider marine environment [23].

While recreational and commercial fisheries may contest MPA enforcement due to relying on natural resources to support their livelihood, MPAs can directly and indirectly enhance the productivity and catch of fisheries. They do this by protecting critical juvenile nursery habitats; supporting stock stability, recovery, and growth; and providing spillover effects into adjacent fishable areas.

Economic Perspectives

Inshore marine environments often become contested spaces when MPAs are proposed near productive or commercially valuable fisheries. In some cases, protection is designated in previously unfished areas, limiting conservation benefits in ecosystems more vulnerable to exploitation [24], [25]. Many commercial fishers argue that existing regulatory frameworks, under the Quota Management System [26] and the Fisheries Act 1996 [27], already provide adequate environmental protection [28], [29]. However, MPAs can enhance fish stock productivity by fostering the accumulation of mature biomass, which may spill over into adjacent fishing zones through density-dependent movements of adult fish and larvae [30], [31].

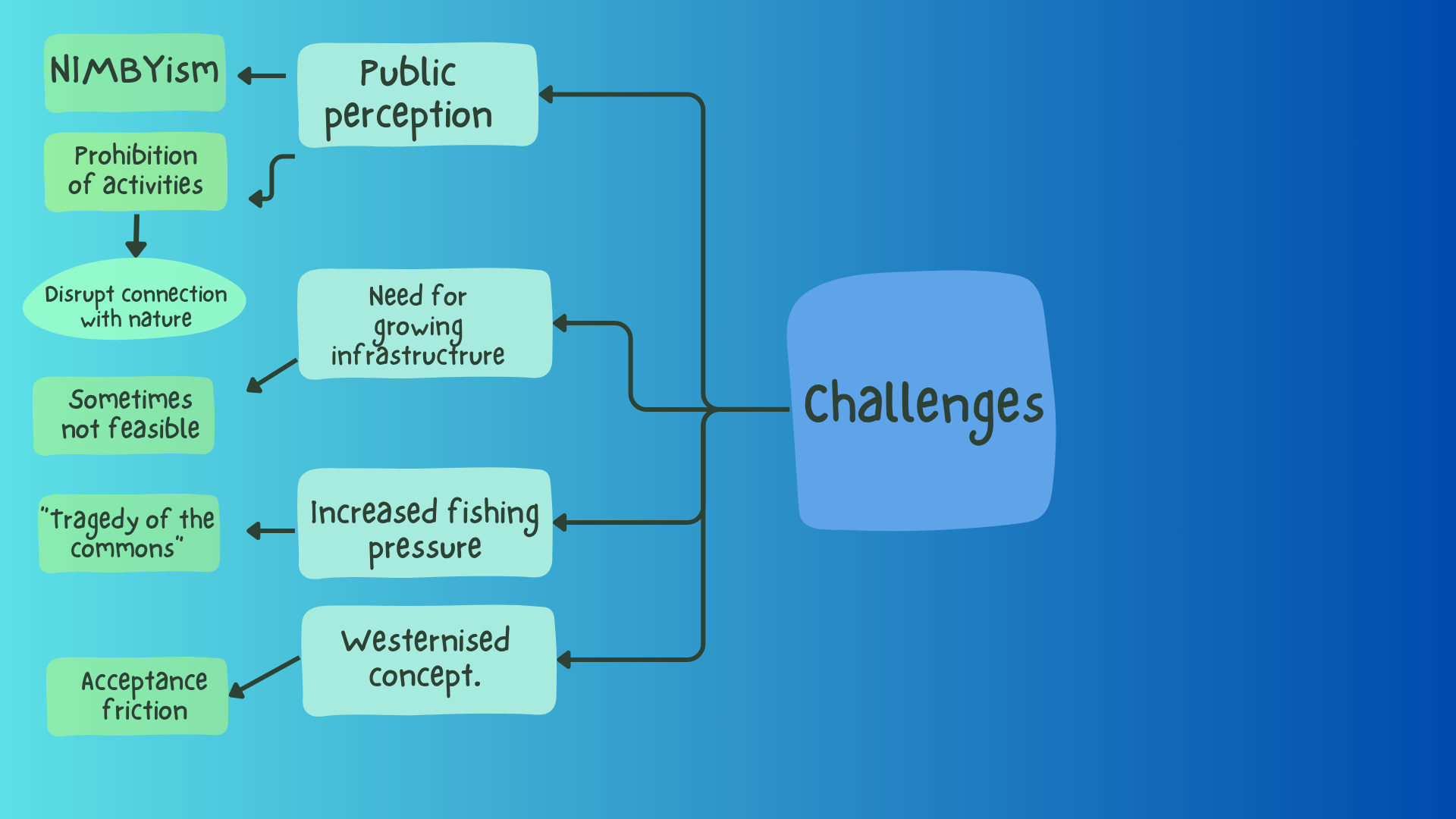

Although spillover effects have been associated with an increased catch per unit effort (CPUE), the benefits are not always sustained. In Aotearoa New Zealand, MPA implementation has sometimes triggered a rebound effect, where an influx of new vessels increases fishing pressure around reserve boundaries, driven by expectations of high productivity [25]. This intensified effort, further heightened by competition among fishers, reflects the classic “tragedy of the commons” where individual fishers maximise landings of limited fish stocks in an open access fishing ground without regard to long-term consequences [32]. Such pressure can undermine conservation objectives, preventing the wide-scale preservation of natural life history traits and degrading benthic habitats through trawling and gear contact [25], [33], [34].

Snapper fisheries illustrate how biological and legal intricacies can undermine MPA effectiveness. Highly valued both commercially and recreationally, snapper are vulnerable due to the narrow gap between size at reproductive maturity (20–30 cm) and legal catch size, which ranges from 25 cm to 30 cm depending on the quota management area. This allows stocks to be harvested before contributing significantly to population recruitment [28], [35], [36], [37]. Furthermore, misalignment between fisheries management and marine protection legislation may limit the potential for MPAs to enhance stock resilience in such species [29], [35].

Ultimately, the impact of MPAs on fisheries is shaped by a complex interplay of biological traits, the distribution of fish over space, regulatory frameworks, and fisher behaviour. While MPAs offer potential conservation and fishery benefits, their success ultimately depends on integrated management that accounts for both human impacts and ecosystem dynamics.

Social Perspectives

Despite most people agreeing with the concept of MPAs, initial public perceptions of specific proposals are often quite low [38]. While locals hardly contend with the scientific evidence that reserves provide wonderful long-term boosts to ecological systems, NIMBYism (Not In My Back Yard) is strong. Many people have compelling connections to the ocean for recreational and sustenance fishing. With MPAs prohibiting such activities, people can fear that their connection will be severed and essential rights will be lost [4]. Existing MPAs in New Zealand have attracted significant tourism, often for recreation and diving, as visitors wish to experience the beautiful, pristine, and ‘untouched’ conditions MPAs have created [4]. However, this influx of people and tourists places a larger demand on existing infrastructure, such as roads, carparks, or docks, for easy access. In some cases, it isn’t feasible to make these upgrades.

However, most MPAs have demonstrated that people embrace them once their benefits become clear, and often become a source of pride for local communities. For example, the Cape Rodney-Okakari Point Marine Reserve (Goat Island) garnered a lot of local support once marine life returned to the seashore and defensiveness whenever poachers attempted to fish in the reserve [4], [39]. This shows that MPAs can lead to a greater understanding and awareness of why protecting our marine environments is so important, as well as positively influencing public attitudes.

There can also be a lot of confusion about what is and isn’t allowed in a reserve, or the misconception that partial-take reserves are better for fishing, which attracts more fishers. Enforcement thus becomes an issue, and the rules are often complex and can lead to accidental non-compliance. Therefore, many New Zealand MPAs opt for full no-take to avoid confusion [38]. Poor Knights, one of New Zealand’s most popular marine reserves for diving, was implemented as a partial-take reserve in 1981, allowing certain fishing under complex rules [40]. However, by 1997 the Minister of Conservation announced it would no longer allow recreational fishing, following decreasing public support for fishing and an increased recognition that the primary purpose of the reserve was to protect the marine ecosystem.

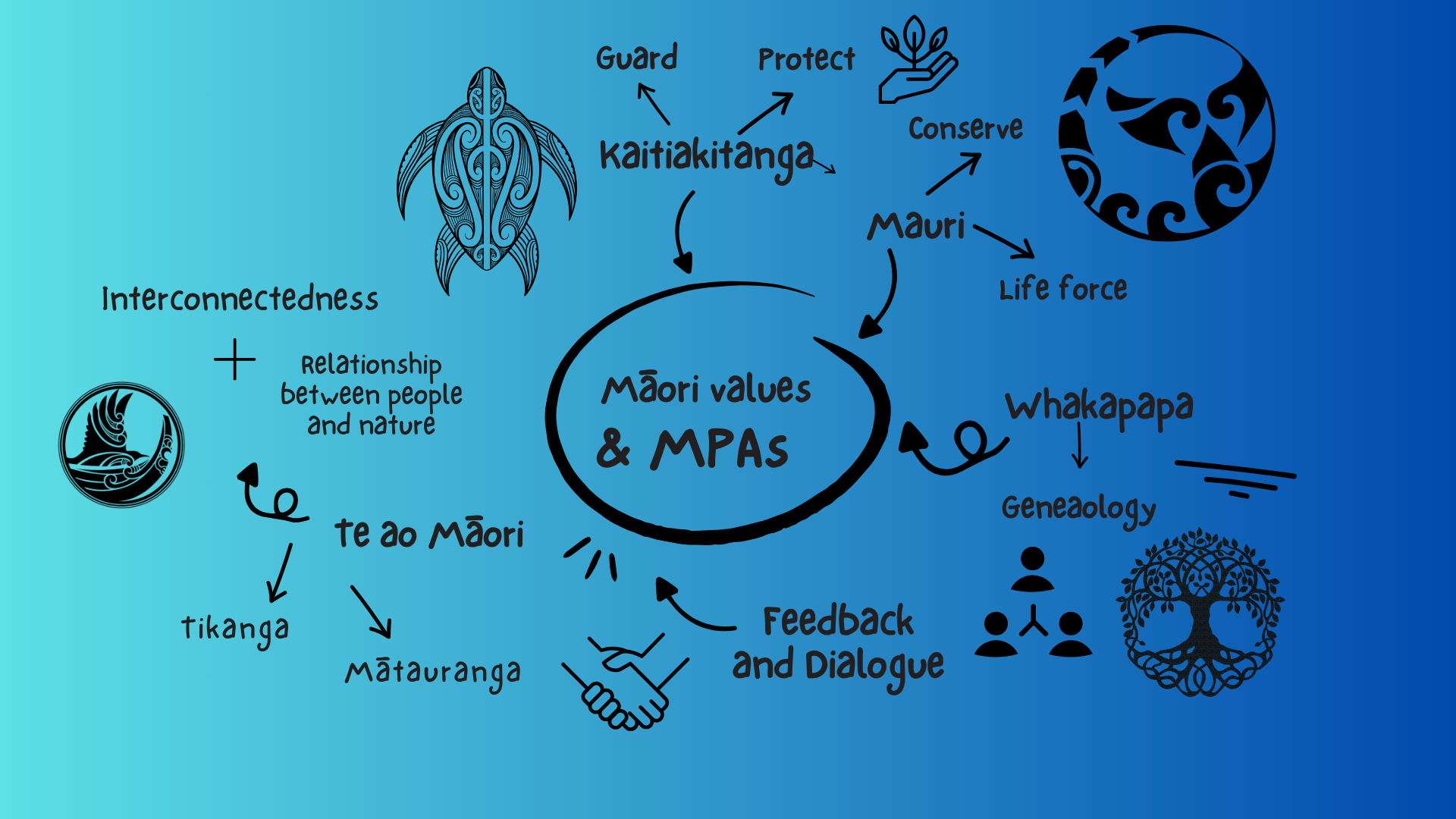

Māori have similar mixed opinions to the establishment of MPAs. Some iwi believe that MPAs will take away their customary fishing rights and that their inflexible nature is impractical when compared with their knowledge and practices of fisheries management, such as taiapure. Others believe that MPAs will be beneficial to science, recreational users, and marine life into the future [4]. Indigenous opinions and inputs are crucial when designing a successful MPA. Integrating mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge systems) into MPAs ensures that we uphold our obligations to Te Tiriti o Waitangi through inclusive co-management and design [4]. Te ao Māori is a more holistic and interconnected worldview compared to the traditional Western science through which MPAs are largely informed. Incorporating values and principles such as kaitiakitanga (environmental guardianship), mauri (life force), and whakapapa (genealogy and interconnectedness) into the design of MPAs helps us to acquire a better understanding of the ocean area being considered for a protected area, as well as aiding in decision-making and enhancing Māori whakapapa to the ocean.

Why MPAs?

MPAs are an essential tool to protect our marine biodiversity and ecological integrity. The benefits and impacts from MPAs go beyond the localised area, as they provide ecological and fisheries benefits to their surroundings. These protected areas contribute to essential ecosystem services, bolster fisheries through spillover effects, and provide cultural, educational, and recreational value. However, MPAs exist within complex social, economic, and legislative landscapes. Some challenges persist, including public resistance, enforcement difficulties, and conflicts with existing fisheries frameworks. The success and formation of MPAs not only relies on science, but also on inclusive, transparent governance that integrates diverse values and knowledge, including te ao Māori. Ultimately, the future of our moana will rely on how we use and care for it.

Figure 2: Challenges faced by MPA developments.

Figure 3: Māori values weaved into creating MPAs.

Figure 1: Benefits of MPAs. Left: recreational, scientific, and environmental improvements within the MPA. Right: adjacent waters that benefit from MPA spillover effects.

[1] B. Halpern, S. Walbridge, K. Selkoe, C. Kappel, F. Micheli, C. D’Agrosa et al., “A Global Map of Human Impact on Marine Ecosystems,” Science, vol. 319, no. 5865, pp. 948-952, Feb. 2008, doi: https://doi. org/10.1126/science.1149345.

[2] H. Fox, M. Mascia, X. Basurto, A. Costa, L. Glew, D. Heinemann et al., “Reexamining the science of marine protected areas: linking knowledge to action,” Conserv. Lett., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-10, Nov. 2011, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755- 263X.2011.00207.x.

[3] K. Davies, A. Murchie, V. Kerr, and C. Lundquist, “The evolution of marine protected area planning in Aotearoa New Zealand: Reflections on participation and process,” Mar. Policy, vol. 93, pp. 113-127, Jul. 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. marpol.2018.03.025.

[4] B. Ballantine, “Fifty years on: Lessons from marine reserves in New Zealand and principles for a worldwide network,” Biol. Conserv., vol. 176, pp. 297-307, Aug. 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. biocon.2014.01.014.

[5] New Zealand, Parliament. Marine Reserves Act 1971. Accessed: June 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.legislation. govt.nz/act/public/1971/0015/latest/ whole.html.

[6] Department of Conservation and Ministry of Fisheries, Marine Protected Areas Classification, Protection Standard and Implementation Guidelines, Wellington, New Zealand, 2008. Accessed: June 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www. doc.govt.nz/Documents/conservation/ marine-and-coastal/marine-protectedareas/mpa-classification-protectionstandard.pdf.

[7] Department of Conservation. “Te Mana o Te Taiao - Aotearoa New Zealand biodiversity strategy 2020.” doc.govt. nz. Accessed: June 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.doc.govt.nz/ globalassets/documents/conservation/ biodiversity/anzbs-2020.pdf.

[8] R. Taylor, M. Anderson, D. Egli, and T. Willis, “Cape Rodney to Okakari Point Marine Reserve Fish Monitoring 2003: Final Report,” Univ. Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2003. Accessed: June 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.doc.govt.nz/documents/ conservation/marine-and-coastal/marine-protected-areas/report-onfish-monitoring.pdf.

[9] T. Haggitt, “Cape Rodney to Okakari Point Marine Reserve and Tawharanui Marine Park Lobster Monitoring Programme: 2009 Survey,” CASL, Warkworth, New Zealand, 2009. Accessed: June 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/ documents/conservation/marine-and-coastal/marine-protectedareas/crop-lobster-survey-2009.pdf.

[10] T. Haggitt, “Cape Rodney to Okakari Point Marine Reserve and Tawharanui Marine Park Reef Fish Monitoring: UVC Survey Autumn 2011,” CASL, Warkworth, New Zealand, 2011. Accessed: June 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.doc.govt.nz/Documents/ conservation/marine-and-coastal/marine-protected-areas/croptawharanui-reef-fish-survey-aug-2011.pdf.

[11] C. Marcos, D. Diaz, K. Fietz, A. Forcada, A. Ford, J.A. Garcia-Charton et al., “Reviewing the ecosystem services, societal goods, and benefits of marine protected areas,” Front. Mar. Sci., vol. 8, pp. 1-37, June 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.613819.

[12] R. Rowley, “Impacts of marine reserves on fisheries,” DOC, Wellington, New Zealand, no. 51, 1993. Accessed: June 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.doc.govt.nz/documents/science-andtechnical/SR51.pdf.

[13] Z. Qu, S. Thrush, D. Parsons, and N. Lewis, “Economic valuation of the snapper recruitment effect from a well-established temperate no-take marine reserve on adjacent fisheries,” Mar. Policy, vol. 134, p. 104792, Dec. 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104792.

[14] R. Babock, S. Kelly, N. Shears, J. Walker, and T. Willis, “Changes in community structure in temperate marine reserves,” Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., vol. 189, pp. 125-134, Nov. 1999, doi: https://doi.org/10.3354/ meps189125.

[15] T. Willis, R. Millar, and R. Babcock, “Protection of exploited fish in temperate regions: high density and biomass of snapper Pagrus auratus (Sparidae) in northern New Zealand marine reserves,” J. Appl. Ecol., vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 214-227, Apr. 2003, doi: https://doi. org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00775.x.

[16] F. Scharf, F. Juanes, and R. Rountree, “Predator size-prey size relationship of marine fish predators: interspecific variation and effects of ontogeny and body size on trophic-niche breadth,” Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., vol. 208, pp. 229-248, Dec. 2000, doi: https://doi. org/10.3354/meps208229.

[17] L. Modica, A. Bozzano, and F. Velasco, “The influence of body size on the foraging behaviour of European hake after settlement to the bottom,” J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol., vol. 444, pp. 46-54, June 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2013.03.001.

[18] R. Cole and D. Keuskamp, “Indirect effects of protection from exploitation: patterns from populations of Evechinus chloroticus (Echinoidea) in northeastern New Zealand,” Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., vol. 173, pp. 215-226, Nov. 1998, doi: https://doi.org/10.3354/ meps173215.

[19] C. Liquete, C. Piroddi, E. Drakou, L. Gurney, S. Katsanevakis, A. Charef et al., “Current status and future prospects for the assessment of marine and coastal ecosystem services: a systematic review,” PLoS. One, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 1-15, July 2013, doi: https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067737.

[20] H. Kotula, “Valuing forest ecosystem services in New Zealand,” Motu, Wellington, New Zealand, Rep. 22-11, 2022. Accessed: June 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https:// motu-www.motu.org.nz/wpapers/22_11. pdf.

[21] A. Port, J. Montgomery, A. Smith, A. Croucher, I. McLeod, and S. Lavery, “Temperate marine protected area provides recruitment subsidies to local fisheries,” Proc. R. Soc., vol. 284, no. 1865, pp. 1-9, Oct. 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1300.

[22] I. Nagelkerken, M. Grol, and P. Mumby, “Effects of marine reserves versus nursery habitat availability on structure of reef fish communities,” PLoS. One, vol. 7, no. 6, p. 36906, June 2012, doi: https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036906.

[23] R. Babcock, “Leigh marine laboratory contributions to marine conservation,” N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 360- 373, Aug, 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080 /00288330.2013.810160.

[24] R. Langton, D. A. Stirling, P. Boulcott, and P. J. Wright, “Are MPAs effective in removing fishing pressure from benthic species and habitats?,” Biol. Conserv., vol. 247, p. 108511, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. biocon.2020.108511.

[25] T. Lohrer et al., “Evidence of rebound effect in New Zealand MPAs: unintended consequences of spatial management measures,” Ocean Coast. Manag., vol. 239, p. 106595, 2023, doi: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106595.

[26] Ministry for Primary Industries, The Quota Management System, Wellington, New Zealand. [Online]. Available: https://www. mpi.govt.nz/fishing-aquaculture/fisheriesmanagement/quota-managementsystem/.

[27] New Zealand, Parliament. Fisheries Act 1996. Wellington, New Zealand. [Online]. Available: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/ act/public/1996/0088/latest/whole.html.

[28] D. M. Kaplan, “Fish life histories and marine protected areas: an odd couple?,” Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., vol. 377, pp. 213–225, 2009, doi: https:// doi.org/10.3354/meps07825.

[29] R. Bess and R. Rallapudi, “Spatial conflicts in New Zealand fisheries: the rights of fishers and protection of the marine environment,” Mar. Policy, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 719–729, 2007, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. marpol.2006.12.009.

[30] G. J. Edgar et al., “Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features,” Nature, vol. 506, pp. 216–220, 2014. [31] S. Jennings, “Patterns and prediction of population recovery in marine reserves,” Rev. Fish Biol. Fish., vol. 10, pp. 209–231, 2000, doi: https:// doi.org/10.1038/nature13022.

[32] L. D. Barnett, “The tragedy of the commons,” Springer, 1982.

[33] S. F. Thrush and P. K. Dayton, “Disturbance to marine benthic habitats by trawling and dredging: implications for marine biodiversity,” Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst., vol. 33, pp. 449–473, 2002, doi: https://doi. org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.15051.

[34] D. Mouillot et al., “Global marine protected areas do not secure the evolutionary history of tropical corals and fishes,” Nat. Commun., vol. 7, p. 10359, 2016, doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10359.

[35] D. M. Parsons et al., “Risks of shifting baselines highlighted by anecdotal accounts of New Zealand’s snapper (Pagrus auratus) fishery,” N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 965–983, 2009, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330909510054.

[36] D. M. Parsons et al., “Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus): a review of life history and key vulnerabilities in New Zealand,” N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 256–283, 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0 0288330.2014.892013.

[37] M. P. Francis and N. W. Pankhurst, “Juvenile sex inversion in the New Zealand snapper Chrysophrys auratus (Bloch and Schneider, 1801) (Sparidae),” Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 625–631, 1988, doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/MF9880625.

[38] N. Taylor and B. Buckenham. “Social impacts of marine reserves in New Zealand,” Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand, 2003. [Online]. Available: https://www.doc.govt.nz/documents/ science-and-technical/sfc217.pdf .

[39] C. Howie. “Swimmers bust alleged poachers at Goat Island marine reserve in Leigh, North Auckland.” New Zealand Herald. Accessed May 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/ swimmers-bust-alleged-poachers-at-goat-island-marine-reserve-inleigh-north-auckland/IDO36PX6JVHAZB5EWFAF5EJX2M/ .

[40] G. R. Harmsworth and S. Awatere. “Indigenous Maori knowledge and perspectives of ecosystems,” in Ecosystem Services in New Zealand : Conditions and Trends, J. R. Dymond, Ed., Lincoln, New Zealand: Manaaki Whenua Press, 2013, pp. 274–286. [Online]. Available: https://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/assets/Discover-Our-Research/ Environment/Sustainable-society-policy/VMO/Indigenous_Maori_ knowledge_perspectives_ecosystems.pdf.

The UoA Marine Science Society is a university club bringing together students of many disciplines with a love for marine science and the ocean. They host a range of academic, social, and beach clean events where all are welcome throughout the year.