Maramataka of the Honey Bee

Maramataka and Honey Bees | Charles Watene

Maramataka (Māori lunar calendar) is an environmental indicator (tohu) that has been used for centuries by Māori to predict the most productive times to perform practices such as gathering kai moana (seafood) and working in the māra kai (garden). This project builds on the idea of a maramataka framework to aid in the decisions that beekeepers make on a daily basis. We evaluated five colonies over the summer of 2023 and 2024 with two minimally invasive assays, foraging activity and ‘runningness’ (speed that bees run on comb). There were also four assays conducted this summer to help reinforce and build a larger dataset that included undertaking and defensiveness. From this we observed the behaviours in order to identify patterns that align with the lunar cycle.

Figure 1: Still image of a brood frame immediately post disturbance in the Runningness assay.

The maramataka is the Māori lunar cycle and has been a key tohu (environmental indicator) for gardening and fishing for centuries. Each phase has different associated attributes and effects that correspond to behavioural patterns in plants and animals. For example, during te rākau-nui (the full moon) it is a bad day to fish for flounder as they are more light sensitive and can see you more easily.

Acts such as the ‘Tohunga Suppression Act 1907’ has led to the loss of knowledge in te ao Māori in relation to mātauranga such as maramataka. Since then, there has been a revitalization from 1975 and has led to more opportunities for relearning and uncovering the traditional frameworks from before early settlers. All of this is to say, when integrating and expanding on this previous knowledge, there is a level of respect and understanding to be made with acknowledgements to the tīpuna (ancestors).

Honey bees, Apis mellifera, are eusocial insects that are either queens or workers if female or drones if male. Workers make up the majority of the colony and change roles in the colony based on age; for example, they go from nursing workers to guarding workers to foraging over the course of their life [1]. When looking into the behaviour and personalities of colonies, this diversity in roles within the colony is important to keep in mind.

Honey bees first arrived in New Zealand around 1839 when the missionaries arrived and have since led to a booming honey industry with the great success of mānuka honey. During this time, Māori beekeepers began developing their own methodologies and observations around honey bees, and have their own specific tohu that they apply when beekeeping.

This project originated from a summer studentship in 2019/2020 when Social Scientist Waka Paul interviewed Māori beekeepers on ways of incorporating tohu with honey bees, and in his final report he created a maramataka for beekeeping in which he associated lunar phases with attributes such as gentleness, brood care and nectar foraging. The current scope of the project has been during the summers of 23/24 and 24/25, in which my team and I conducted behaviour assays on colonies in order to align patterns with the lunar cycle and observe if there are correlations between the maramataka calendar created by Waka.

Last summer at Plant and Food Research (PFR) Kirikiriroa-Hamilton, we observed 5 colonies with two insightful and unintrusive assays twice a week from November 2023 to April 2024 (accounting for factors such as weather and holidays).

‘Foraging activity’ and ‘Runningness’ were the two assays that we performed on the colonies. Foraging activity is assessed by taking four one-minute counts of the total number of worker bees returning to the hive, with and without pollen [2]. Bees that don’t have obvious collections of pollen may have been collecting water or nectar, or scouting for new resources. The numbers of non-pollen and pollen foragers, as well as the total, gives us insight into the status of the colony. These results can vary drastically from 0 to 60 pollen foragers, or 0 to 80, or even 100 non-pollen foragers in a one minute count.

Runningness was assessed by recording bees moving on the surface of a comb over a one-minute period before and after a standardized disturbance was applied. We calculated the average speed and distance moved of 10 bees before and after a standardised impact on a frame [2]. Runningness is an ideal metric for how reactive a colony can be when bumped into or moved to another site; an aspect of beekeeping that can be often overlooked.

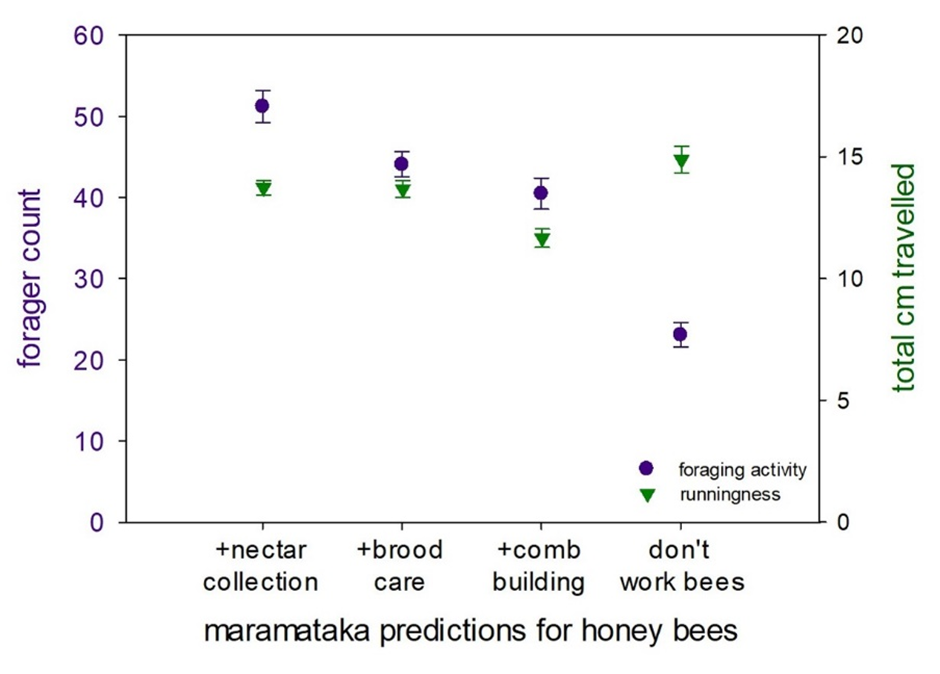

When aligning our results with the maramataka created by Waka, we found that days associated with tohu to not work with bees had lower foraging behaviour and higher distance and activity in the runniness assay. We also can see that foraging behaviour was at its highest on days that describe nectar collection. These results were significant, but there were also trends that appeared to go against the general prediction of days of the maramataka such as ‘alright’ and ‘ki te hoe’. In these frameworks there were non-significant trends such as pollen foraging being lowest on medium energy ‘alright’ days and high pollen foraging on the ‘ki te hoe’ waning days. In trials like this with so many variables and working with bees it can be hard to have significant data, which is what makes the correlations between our work and Waka’s framework so intriguing.

Figure 2: Results.

In terms of this current field season, 24/25, we are strengthening our foraging activity assay results with bi-weekly observations, but this time we put the runningness assay on hold and introduced two other non-intrusive assays: ‘Undertaking’ and ‘Defensiveness’ for our new cast of colonies. In addition, we also had five colonies in our apiary undergoing pollen sampling twice a week using pollen traps in the hopes of discovering more patterns with the lunar calendar.

Undertaking, or the necrophoresis in the honey bee colony, is how bees deal with the passing of fellow comrades [3]. This specialized task is taken up for workers at around the age of 12.5 days [3]. The undertaking assay involved a selection of 100 dead bees that were spray painted, frozen, and then deployed into the back of the colony for half an hour. From the half hour point, we counted the remaining painted bees and can get a percentage of cleaning over time in regard to the day of collection and also compared to the other colonies

Defensiveness of the colony can be done in a few ways and in the past has been mostly used to identify potential Africanised bees [4]. The method we use involves waving a faux-suede flag in front of the colony for one minute or until a bee stings the flag (if no bee has stung the flag at this point, we induce one to sting it); once there is a sting on the flag it is waved for an extra minute before being sealed away, and the number of additional stingers collected on the flag is counted [4]. Initial observations show that the propensity of the colonies to sting the flag varies between the different days.

The pollen traps we use have a 15% efficiency at collecting pollen, which gives us a great look into what they’re collecting and how it varies without depriving the colony of pollen. These traps are placed under the hive at the start of the week, on the second day we exclude the pollen data as the foraging is affected and each following day, the pollen is sampled and recorded until it is taken off for the weekend to reduce additional stress on the colonies. There is a new summer student this year working in and around this aspect of the process and looking into the changes in weight and colour variety in the pollen.

Overall, there are still a lot of variables at play, and more results to come. This is a really exciting and interesting area that I hope to explore and expand on with my team. Kua hua te marama (a cycle is completed). Watch this space.

[1] G. Mark, A. Boulton, T. Allport, D. Kerridge, and G. Potaka-Osborne, “‘Ko Au te Whenua, Ko te Whenua Ko Au: I Am the Land, and the Land Is Me’: Healer/Patient Views on the Role of Rongoā Māori (Traditional Māori Healing) in Healing the Land,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 14, p. 8547, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148547.

[2] A. Ahuriri- Driscoll, “HE KŌRERO WAIRUA: Indigenous Spiritual Inquiry in Rongoā Research,” MAI Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 33–44, May 2014, [Online]. Available: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/4e5aae1f-379a-4027-a863-fe43deeaf22e/content

[3] Rhys Jones, ‘Rongoā – medicinal use of plants’, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/rongoa-medicinal-use-of-plants (accessed 18 January 2025)

[4] “Demystifying Rongoā Māori: Traditional Māori Healing,” Best Practice Journal New Zealand, no. 13, pp. 32–36, May 2008, [Online]. Available: https://bpac.org.nz/bpj/2008/may/docs/bpj13_rongoa_pages_32-36. pdf

[5] J. Koea and G. Mark, “Is there a role for Rongoā Māori in public hospitals? The results of a hospital staff survey,” New Zealand Medical Journal, vol. 133, no. 1513, Art. no. ISSN 1175-8716, Apr. 2020, [Online]. Available: https://nzmj.org.nz/media/pages/journal/vol-133-no-1513/ is-there-a-role-for-rongoa-maori-in-public-hospitals-the-results-of-ahospital-staff-survey/ddf5d7c29e-1696474977/is-there-a-role-forrongoa-maori-in-public-hospitals-the-results-of-a-hospital-staff-survey.pdf

[6] Alan Ward. ‘Carroll, James’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https:// teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2c10/carroll-james (accessed 18 January 2025)

[7] M. Lis-Balchin, S. L. Hart, and S. G. Deans, “Pharmacological and antimicrobial studies on different tea-tree oils (Melaleuca alternifolia, Leptospermum scoparium or Manuka and Kunzea ericoides or Kanuka), originating in Australia and New Zealand,” Phytotherapy Research, vol. 14, no. 8, pp.623– 629, Jan. 2000, doi: 10.1002/1099- 1573(200012)14:8.

[8] E. Rabie, J. C. Serem, H. M. Oberholzer, A. R. M. Gaspar, and M. J. Bester, “How methylglyoxal kills bacteria: An ultrastructural study,” Ultrastructural Pathology, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 107–111, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.3109/01913123.2016.1154914.

[9] J. H. Koia and P. Shepherd, “The Potential of Anti-Diabetic Rākau Rongoā (Māori Herbal Medicine) to treat Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) Mate Huka: A review,” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 11, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00935.

[10] S. Chen, H. Jiang, X. Wu, and J. Fang, “Therapeutic effects of quercetin on inflammation, obesity, and type 2 diabetes,” Mediators of Inflammation, vol. 2016, pp. 1–5, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1155/2016/9340637.

[11] S. E. Hill, A. Yung, and M. Rademaker, “Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and antibiotic resistance in children with atopic dermatitis: A New Zealand experience,” Australasian Journal of Dermatology, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 27–31, Dec. 2010, doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00714.x.

[12] N. Shortt et al., “Efficacy of a 3% Kānuka oil cream for the treatment of moderate-to-severe eczema: A single blind randomised vehicle-controlled trial,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 51, p. 101561, Jul. 2

[13] B. Marques, C. Freeman, and L. Carter, “Adapting Traditional Healing Values and Beliefs into Therapeutic Cultural Environments for Health and Well-Being,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 426, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010426

[14] Ahuriri-Driscoll, Baker, Hepi, Hudson, Mika, and Tiakiwai, “The Future of Rongoā Māori: Wellbeing and Sustainability,” Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd & Ministry of Health, FW06113, Sep. 2008. Accessed: Jan. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/064fd078-d860- 4887-bf2f-87cdb2081321/content

[15] J. Koea, G. Mark, D. Kerridge, and A. Boulton, “Te Matahouroa: a feasibility trial combining Rongoā Māori and Western medicine in a surgical outpatient setting,” New Zealand Medical Journal, vol. 137, no. 1597, pp. 25–35, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.26635/6965.6417.

Charles is a Graduate from the University of Waikato who completed this research trial with PFR’s Bee Biology and Productivity Team last summer as a participant in Te Rito Summer Studentship. He has worked with bees in Ruakura for over two years. He is allergic to bees.