Heat Shock Proteins: The Firefighters in Your Cells

Molecular and Cell Biology | David Lu

The heat shock response is one of the most conserved systems, existing in all known species. Heat shock proteins are chaperone molecules that help proteins fold into their native state. They exist in every body system and thus may be implicated in a variety of diseases. This article explains the importance of heat shock proteins, their function, and why they are implicated in many common diseases.

Overview

Protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is a fundamental equilibrium system in cells that must be carefully maintained for a cell to remain functional. Proteostasis involves (1) protein synthesis, (2) protein maintenance, and (3) protein degradation [1, 2]. Protein synthesis is concerned with producing the correct amount of protein for the cell to function, without having excess proteins that waste resources - this involves co-translational and post-translational modifications such as protein folding and signal targeting to determine whether they will be complete as a mature protein. Protein maintenance is concerned with the quality of the protein and whether the protein is folded, unfolded, misfolded, or aggregated - this affects the protein’s ability to function, and where the protein is targeted or localised to within or outside the cell. Protein degradation is when a protein is targeted for ubiquitination or for autophagy, usually to recycle the amino acids and remove dysfunctional proteins [1, 2, 3]. This article will focus mainly on the protein maintenance and protein degradation aspect of proteostasis, particularly on the Heat Shock Response, as it promotes protein maintenance and prevents degradation of healthy proteins that would have otherwise denatured under stress conditions.

The heat shock response is a physiological mechanism to protect proteins, and thereby cells from extreme conditions, and heat shock proteins (HSP) play a key part of this process. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are proteins produced by cells in response to stressors such as heat, UV radiation, infection, oxidative stress, and many more. They act as molecular chaperones for RNA and other proteins, helping them fold properly while also preventing their aggregation under stressful conditions [4, 5, 6]. With respect to proteins, structure is synonymous with function since the 3D structure causes specific bonds and interactions to be formed at specific regions of the protein, especially in enzyme proteins where substrates can bind at active sites [7, 8]. Therefore, misfolding and aggregation leads to the denaturation of proteins, meaning that their function is impaired as the RNA strands are misaligned, or the quaternary cofactors are in the incorrect position. Additionally, misfolding may cause new interactions to form between amino acids and relevant cofactors, leading to a gain of function within the protein, which may have toxic outcomes depending on how severe this newfound function is. If enough of the cellular components are malformed, the cell could be rendered defective and is marked for apoptosis, phagocytosis or degradation, resulting in cell death [7, 8]. Thus, heat shock proteins play an integral role in proteostasis and maintaining functional cellular processes. If the heat shock response is ineffective, it may lead to clinical complications as abnormal protein can lead to abnormal or loss of function, which may therefore cause disruptions to physiological systems in the body.

The Discovery of the Heat Shock Response

The heat shock response was first discovered in drosophila when chromosomes “puffed up” in response to various stresses [5, 9]. Researchers then explored this phenomenon among other organisms, which all seemed to show the same mechanism of action in response to stresses of various types. mRNA sequencing was carried out on these chromosomal puff sites and it was found that these encode genes that produce HSPs in vivo [5]. These HSPs were determined to protect proteins during extreme stress conditions. It was further discovered that priming cells with mild stress causes heat shock proteins to be expressed, enabling the cells to survive subsequent stresses that may be more extreme [6]. The genes for the heat shock proteins are some of the most conserved regions in the genome, along with the genes that encode ribosomes for translation [4, 5, 6, 10]. These genes have existed in archaebacteria from 3.5 billion years ago all the way to today, where all the currently existing species today still have this protein system. This is because they are essential to the survival of organisms, otherwise they would have been selected out by evolution [4 - 6].

Heat Shock Protein Transcription

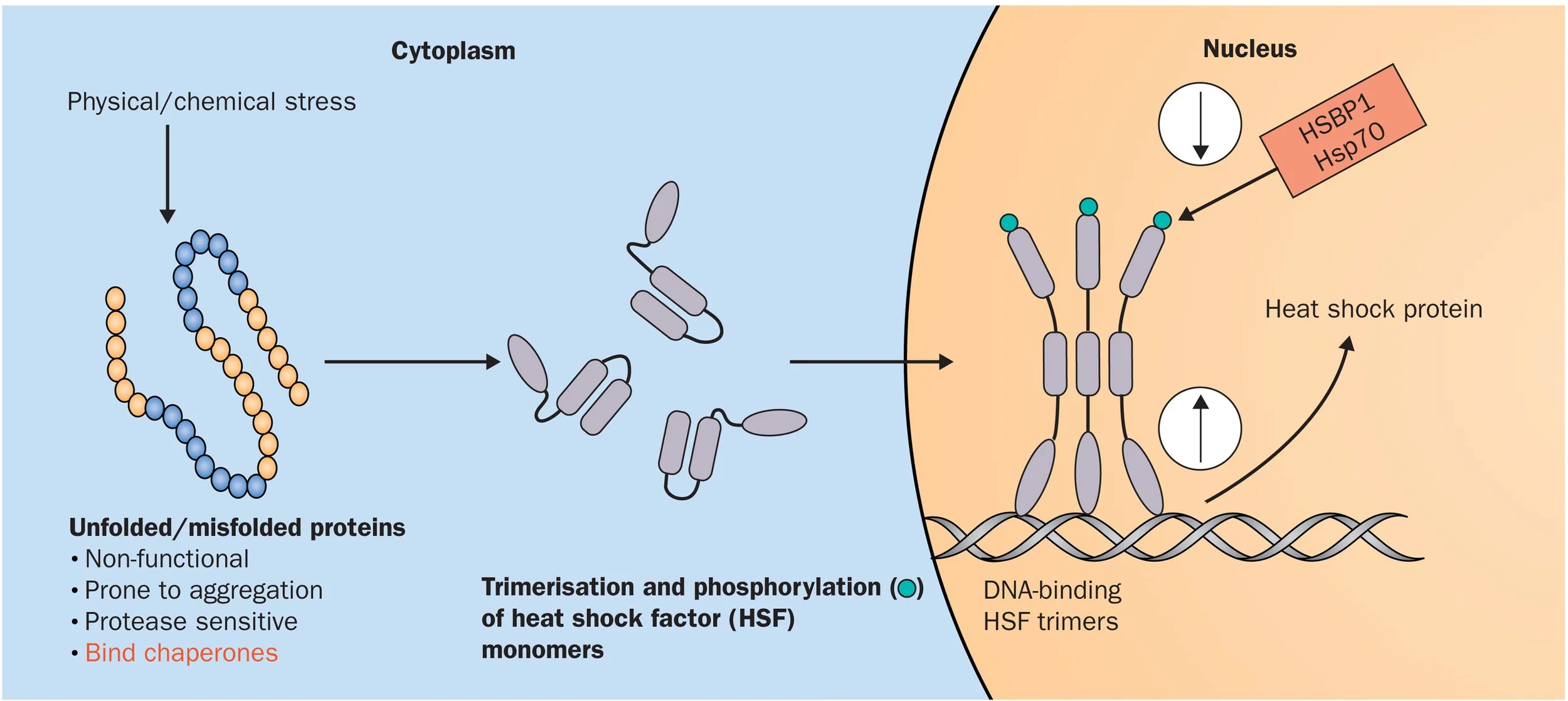

When a stressor is applied to the cell, transcription is initiated by heat shock factors (HSFs). Vertebrates have HSF1-4, and HSFX/Y each of which has various functions. For example, HSF1 responds to heat shock and elevated temperature, HSF2 is involved in differentiation of cells and the development of tissue and organs, and HSF3 is co-activated with HSF1 in response to chemical stress. These transcription factors are the first step of the heat shock response, and when activated, they oligomerize and translocate to the nucleus where they may activate transcription for the relevant heat shock proteins [6, 10, 11].

HSFs bind to the heat shock elements - specific DNA sequences at the promoter region of the target proteins, initiating transcription of the heat shock proteins [10, 11]. Once the heat shock proteins are translated and become mature proteins, they act as protein remodelers, allowing misfolded proteins to bind and refold into another conformation, or into their native conformation, rescuing their function [12]. The heat shock proteins have a substrate binding domain, and a nucleotide binding domain which specifically binds ATP/ADP. When the HSP is bound to ATP, the substrate binding domain is open and misfolded proteins may bind at this site. Once the protein is bound, the heat shock protein chaperone attempts to refold the bound protein. This may result in the protein refolding into its native state, or into another state, and once the ATP is hydrolysed to ADP, this refolded protein is released [13].

The Heat Shock Protein Family

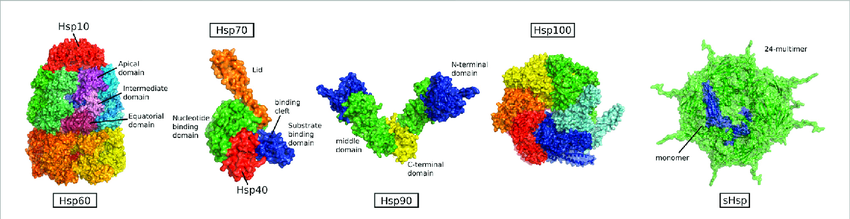

The heat shock proteins are a family of proteins that work in tandem to aid in protein folding. Some are always active while others are induced by stressors. The most studied heat shock proteins include Hsp40, Hsp60, Hsp70, and HSP90 with the numbers referring to their size in kilodaltons [6, 10, 11]. Each of these HSPs have a specific function within the Heat Shock Response system. HSP40 recruits and activates HSP70, acting as a co-chaperone for it while also being able to refold proteins itself. HSP60 assists in folding proteins and prevents aggregation of misfolded proteins. HSP70 is integral to proteostasis as it is the main HSP responsible for holding and refolding misfolded proteins. HSP70 is the most inducible HSP under stress but is also constitutively expressed meaning it is constantly refolding proteins. It exists in almost every cellular component including the nucleus, cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and is even secreted for extracellular functions. HSP90 inhibits aggregation of proteins and stabilises substrate proteins such as kinases and steroid receptors. HSP100 helps hold misfolded proteins and mitigates their effects in severe stress conditions [5, 6].

Conversely, heat shock protein underexpression contributes to neurodegenerative diseases. This is because heat shock proteins typically aid in the removal and prevention of protein aggregates and misfoldings, and many neurodegenerative diseases are caused by misfolded protein aggregates. An example of this is Alzheimer’s disease, which is a neurodegenerative disease affecting memory. The main characteristic of Alzheimer’s is the aggregation of tau and amyloid-beta plaques in neurons of the brain. Normally heat shock proteins, particularly HSP70, would help clear these misfolded proteins and maintain the normal physiological function of the neuron, but when they are underexpressed, they cannot clear the aggregated plaques fast enough [6, 15].

Interestingly, in cardiovascular disease, heat shock proteins may either be protective or harmful depending on what disease it is, and which heat shock protein is affected. In some cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction - which causes the death of cardiomyocytes - the heat shock proteins inhibit apoptosis which protects the heart. However, in atherosclerosis HSP60 may initiate the atherosclerotic pathogenesis. HSP60 is expressed on endothelial cells and if there is an infection, the human HSP may cross-react with bacterial HSPs leading to an inflammatory response and the dysfunction of blood vessels. This further accelerates the progression of the atherosclerotic plaque and may lead to an arterial occlusion [6].

Conclusion

Heat shock proteins are ubiquitous to all organisms and maintain the protein equilibrium and are vital to ensuring that cells are functioning correctly. This is further emphasised by the conserved nature of the heat shock protein superfamily genes and the heat shock response system. Due to their relevance in all physiological functions, they are often implicated in many diseases. Thus, future therapeutic targets and research for the dysfunction of heat shock proteins implicated in cancer, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular disease may be beneficial for the treatment of these conditions and lead to improved health outcomes.

Figure 1: Transcription Initiation by Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1) in Response to Stress. Stress causes proteins to misfold, causing HSFs to become activated. HSF1 binds to DNA in the nucleus of the cell to initiate transcription for Heat Shock Proteins [12].

Figure 2: The Heat Shock Proteins and their Domains. Proteins can bind to the functional domains of the heat shock proteins in the open state and attempt to refold with ATP bound. They are then released after ATP hydrolysis to ADP [14].

[1] Kurtishi, A., Rosen, B., Patil, K. S., Alves, G. W., & Møller, S. G. (2018). Cellular proteostasis in neurodegeneration. Molecular Neurobiology, 56(5), 3676–3689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1334-z

[2] Jayaraj, G. G., Hipp, M. S., & Hartl, F. U. (2019). Functional modules of the proteostasis network. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 12(1), a033951. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a033951

[3] Cooper, G. M. (2000). Protein degradation. The Cell - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9957/

[4] Tutar, L., & Tutar, Y. (2010). Heat Shock proteins; An overview. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 11(2), 216–222. https://doi. org/10.2174/138920110790909632

[5] Hu, C., Yang, J., Qi, Z., Wu, H., Wang, B., Zou, F., Mei, H., Liu, J., Wang, W., & Liu, Q. (2022). Heat shock proteins: Biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. MedComm, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.161

[6] Singh, M. K., Shin, Y., Ju, S., Han, S., Choe, W., Yoon, K., Kim, S. S., & Kang, I. (2024). Heat shock response and heat shock proteins: Current understanding and future opportunities in human diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(8), 4209. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms25084209

[7] Butreddy, A., Janga, K. Y., Ajjarapu, S., Sarabu, S., & Dudhipala, N. (2020). Instability of therapeutic proteins — An overview of stresses, stabilization mechanisms and analytical techniques involved in lyophilized proteins. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 167, 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijbiomac.2020.11.188

[8] Bhagavan, N., & Ha, C. (2015). Three-Dimensional structure of proteins and disorders of protein misfolding. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 31–51). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-416687-5.00004-x

[9] Ritossa, F. (1962). A new puffing pattern induced by temperature shock and DNP in Drosophila. Experientia, 18(12), 571-573.

[10] Vihervaara, A., & Sistonen, L. (2014). HSF1 at a glance. Journal of Cell Science, 127(2), 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.132605

[11] Åkerfelt, M., Morimoto, R. I., & Sistonen, L. (2010). Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development and lifespan. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 11(8), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nrm2938

[12] Pockley, A. G. (2003). Heat shock proteins as regulators of the immune response. The Lancet, 362(9382), 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0140-6736(03)14075-5

[13] Dubrez, L., Causse, S., Bonan, N. B., Dumétier, B., & Garrido, C. (2019). Heat-shock proteins: chaperoning DNA repair. Oncogene, 39(3), 516– 529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-019-1016-y

[14] Törner, R., Kupreichyk, T., Hoyer, W., & Boisbouvier, J. (2022). The role of heat shock proteins in preventing amyloid toxicity. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fmolb.2022.1045616

[15] Sharp, F. R., Massa, S. M., & Swanson, R. A. (1999). Heat-shock protein protection. Trends in Neurosciences, 22(3), 97– 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166- 2236(98)01392-7

David Lu is an MBChB III student who has a wide array of interests ranging from neuroscience to cancer biology to law and civics. In his spare time, he enjoys baking, playing video games, and hanging out with friends.