Experiences with Kauri Ecosystems

Kauri and Ecosystem Processes | Mitchell Keys

The Summer Research Scholarship Project “SCI118: Ecosystem Processes in Kauri Forests” involved field trips out to Huapai and the Waitakere Ranges on sampling campaigns. On these trips many different samples were collected, such as soil, fine roots, loose litter, and more. Following these field trips the laboratory work included analysis on the various samples that were collected, which involved cleaning roots for image analysis and processing soil. On top of this, the project also involved a dendrochronology conference, along with some vineyard sampling in Blenheim.

Introduction

My Summer Research Scholarship was granted for project SCI118: Ecosystem processes in kauri forests. Supervising this project was Professor Luitgard Schwendenmann from the School of Environment, whose work primarily focuses on the cycling of carbon, nutrients and water in the soil-plant-atmosphere system [1]. Through this research I also had the opportunity to work with current PhD and master’s students under Luitgard, all of whom were researching different aspects of kauri trees and their ecosystems.

Due to the differences between each of these studies, there were multiple field sites involved which were visited over the research period. These included the uninfected (in relation to kauri dieback) Huapai Scientific Reserve, The Cascades, Piha, and Huia sites of the Waitakere Ranges. At the three Waitakere sites, two sub-areas of each site were used for sample collection, with one being referred to as “upper” and the other “lower”. This resulted in six sites to visit across the Waitakere Ranges: Cascades Upper, Cascades Lower, Piha Upper, and more. The significance of two different sub-sites at each location was because one of them was found to be infected with kauri dieback, whereas the other was not. This allowed for the collection of samples which could then be used to compare impacts of the disease. As a huge fan of the natural beauty here in Aotearoa New Zealand, these field trips have been such an amazing experience for me to get outdoors and see what the Auckland region has to offer. From the flat forest path lined with large kauri trees at Huapai, to the steep slopes of the Cascades, over to the dense kauri and ponga forests of Piha (Figure 1), the sites visited on this field trip provided some wonderful views of Tāmaki Makaurau’s forested landscapes.

Field Trips

My experience on this project began in late October when I was invited to attend a sampling field trip to the Huapai site. After loading all of our gear (such as backpacks, a soil auger with accompanying spatula, and some lunch) into one of the School of Environment vehicles, our group for the day drove off to the Huapai Scientific Reserve. Upon arrival at the site, I was in awe at the majesty of the kauri trees present, some of which stood towering over the surrounding canopy. While Luitgard and master’s student Lilly were busy collecting tree cores for dendrochronological studies, my work for the day involved collecting soil samples of staggered depths with PhD student Melanesia. This soil was collected at each of the seven trees used in this study, and up to a depth of 110cm where possible. On the second day of this field trip, instead of pulling up soil, tree climbers were hired to ascend the kauri trees and remove larger branches for us on the ground to process into smaller pieces. This involved the cutting of a section of branch and separation of the bark from the woody tissue which was bagged separately, the removal and bagging of smaller twigs which were also stripped of their bark, and the removal and collection of leaves.

Over the course of the summer scholarship, most of the field work I was involved in was out at the Waitakere Ranges across the six different sites mentioned previously. These sites required a much longer hike out to reach them, however the view of the surrounding landscape was incredible. At these sites, there were three separate sampling campaigns which I was a part of; these were for soil and root cores, soil auger samples, and loose litter collection.

The first of these campaigns that I was involved with was the soil and root core (Figure 2) collection for root analysis. Three soil cores were originally placed in each corner of the six Waitakere Ranges plots back in 2022 and were all filled with peat and sand in the bottom half, and only peat in the top half. Of these three cores, one was placed under the canopy of a kauri tree, one directly under the dripline (where the majority of water coming off the canopy lands), and one under a broadleaf (non-kauri tree) for comparison. Over the last three years, roots have been able to grow through the mesh casing of the cores. When we collected these cores, we would cut around them in the ground with a knife, ensuring that any roots which had grown into the core would remain in there once the core was pulled out of the ground. These cores were then separately bagged up and taken to the lab for processing.

The next campaign to the Waitakere Ranges that I was involved in was collecting soil auger samples which were to be used in soil pH, nutrient, and particle size analysis. On these trips (where possible) a few centimetres of organic top-layer soil were collected at each corner of every site, along with three 10cm deep samples of mineral soil. These were all bagged and sent back for processing. On the final sampling campaign to the Waitakere Ranges, loose litter was collected from litter traps which had previously been set up in four rows (labelled A, B, C, and D) of five across each site. Over time, leaves and twigs from the overlying canopy will fall into these traps, ready for collection. On these trips, a brush and shovel was used to scoop up all the loose litter present in the traps and transfer it to labelled paper bags, ready to send back to the lab.

Figure 2: One of the soil and root cores which were collected from the Waitakere Ranges. (M. Keys, 2024)

Laboratory Work

Following each field trip, processing work back in the laboratory was required so that the samples were ready for analysis. This was different for each of the samples, which allowed me to try out many of the different processing techniques used in the School of Environment. The first of which I was involved in was the soil and root cores. For these samples, the cores were carefully cut open and separated into two bowls representing the two halves of the core: peat, and peat + sand. From here, each half was washed through a two millimetre, one millimetre, and 250μm sieve. This resulted in four tin pots from each half sample: roots, and three sizes of peat/peat + sand (two millimetre, one millimetre, and 250μm). Following this, the peat samples were placed into the laboratory ovens at 40°C to remove all moisture and were then weighed. The root samples were placed into a laboratory fridge before being cleaned of excess peat and scanned under high resolution and separated by species (kauri and non-kauri) for future analysis.

When the soil auger samples were returned to the lab, they were also placed into 40°C ovens to remove all moisture. Once dry, the soil was removed and ground down into two sample sizes, two millimetre and 125μm, using a mortar and pestle. These samples were then weighed depending on the type of soil; organic layer soil was weighed to four grams and five grams for pH and nutrient analysis respectively, whereas mineral layer soil was weighed to 10g, 10g and five grams for particle size, pH, and nutrient analysis respectively.

Dendrochronology Experience

I was also invited to attend the 2025 New Zealand and Australia Dendrochronology Conference, as it was all set up and put into motion by Associate Professor Gretel Boswijk from the School of Environment, alongside Professor Luitgard Schwendenmann. Speaking at this conference were academics and students discussing their research around dendrochronology, something which I am extremely interested in but at the time had not had much practice with. There were many different topics being covered across the two day conference, ranging from climate reconstruction to ecology and archaeology! Being able to discuss these topics and be involved with these conversations was a great experience. Following the conference, I was invited to be a part of a dendrochronological study in the laboratory; the tree core samples collected back in my first field trip to Huapai needed processing and analysis. Two five millimetre wide cores had been taken horizontally from the seven trees at Huapai, with one from the north and one from the south side. To process these cores so that the growth rings were visible, I took them to the Earth Science Processing Lab and spent a day sanding the cores down so that they had a smooth and clean finish, perfect for analysing under a microscope.

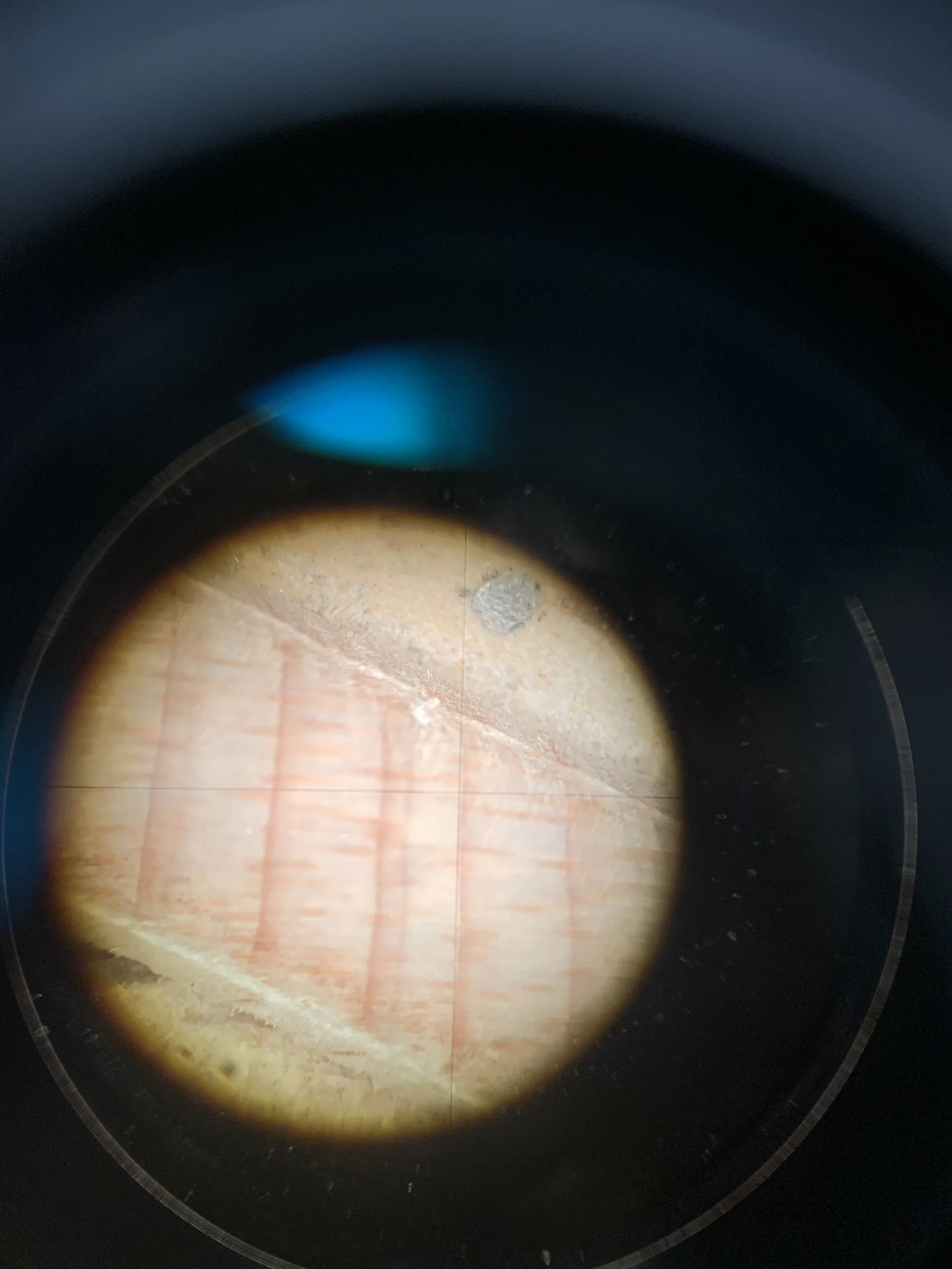

Back in the dendrochronology lab there is a microscope + track setup which moves the core slowly under the eyepiece, allowing for accurate measurement of ring size (Figure 3). Once this is completed for the northern and southern cores, a graph showing the width of each ring is given, allowing for interpretation of its growth. These graphs are able to be overlaid, and if all has gone well we would expect to see the trend of growth being similar between the cores. If there are issues present, such as false rings being counted when they shouldn’t be, there is an analysis stage of working back through the core and graph (from the most recent ring backwards in time) to iron out any issues. Once this graph is complete, it can be overlaid with other previous graphs made of kauri trees from the Huapai Scientific Reserve, both confirming the accuracy of the newer samples and reinforcing the trend of all the cores.

Blenheim Trip

The final piece of my research was in Blenheim, helping out on a project for Dr. Itxaso Ruiz, a post-doctoral research fellow from Spain. This research was focussed on vineyards (Figure 4), and the depth from which grape vines draw their water up from the soil. This field trip took place over six days, with collection from vineyards across the Blenheim area. This research was supported by Plant and Food Research, who were involved in helping us around the vineyards and providing equipment. On these field trips my main role was collecting soil auger samples to a depth of 130cm. On the first day we were working in a vineyard situated on recent fluvial typical loam/silt, and so the 130cm was relatively easy to dig to. However, on subsequent days this was not the case, as the soil types became much harder to dig into, resulting in Plant and Food Research providing us with an automatic auger to dig the final samples. While still down in Blenheim, we went for a drive around the Marlborough Sounds, which provided stunning scenery. The final part of the research that I was involved in was the processing of the grapes collected in Blenheim. Once back in the lab, the grapes (which had been drying for one week at 85°C) were run through a milling machine into one millimetre powder, ready for analysis.

Figure 3: The view down a microscope onto one of the kauri cores collected at Huapai. (M. Keys, 2025)

Figure 4: The view over the vineyards when flying into Blenheim Airport. (M. Keys, 2025)

Conclusion

In conclusion, I had a wonderful time over the break as a Summer Research student and would definitely recommend applying for it to anyone reading this article! It was great being able to learn outside of the lecture theatre and really see how research goes on out in the field or in the laboratory, and to be involved in some really interesting on-going projects! Working with such a wide variety of people all focussing on a specific branch of this topic provided a great chance for me to get a taste of what this area of research has to offer, inspiring my own up-and-coming master’s thesis!

Figure 1: The forest at Piha Lower. Kauri trees and ponga (silver fern) are present. A green loose litter collection bin is visible too. (M. Keys, 2024)

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Professor Luitgard Schwendenmann, my supervisor behind this summer project, for organising and putting everything covered here into motion, and for having me on board over the summer. I would like to thank Dr. Itxaso, PhD students Melanesia and Siqi, master’s students Lilly and Keming, and everyone involved in our larger research group for inviting me to help with work on your projects and teaching me everything there is surrounding your branches of kauri research. I would also like to thank Associate Professor Gretel Boswijk and master’s student Em for teaching me the ropes around dendrochronology, through the conference and laboratory.

[1] L. Schwendenmann. “Research Interests”. University of Auckland Profiles. https://profiles.auckland. ac.nz/l-schwendenmann/grantsB. Sozen, Deniz Conkar, and J. V. Veenvliet, “Carnegie in 4D? Stemcell-based models of human embryo development,” Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, vol. 131, pp. 44–57, Nov. 2022, doi: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2022.05.023.“

Mitchell has just completed a Bachelor’s Degree in Environmental Science, and is beginning a Masters of Environmental Science this year. He is originally from Northland, but has been studying in Auckland. He loves the beautiful landscape in Aotearoa, and loves doing anything that gets him out there.