Are we flushing our privacy down the drain? The ethics of wastewater-based epidemiology

Wastewater-based Epidemiology and Ethics | Mackay Price

A succinct summary of 6,000 years of sewage, sanitation, and its surveillance

For much of human history, waste has been seen as the antithesis of health. Ancient Mesopotamian texts reference Šulak, a toilet demon responsible for various diseases. Fittingly, the name Šulak is derived from the phrase ‘dirty hands’ [1]. While sewage may no longer be described in such aetiological terms, human waste still poses a major health risk; approximately one million people die each year from waterborne diseases [2].

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that for as long as humans have built permanent settlements, they have devised ways to remove waste as efficiently as possible. From rudimentary toilets in Ancient Mesopotamia some 6,000 years ago, to the underground sewers of the Roman Empire, and later, the labyrinthine sewer networks of 19th-century Europe, the development of civilisation can be traced through its sewage infrastructure. The systematic connection of people to pipes has laid the foundation for wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE).

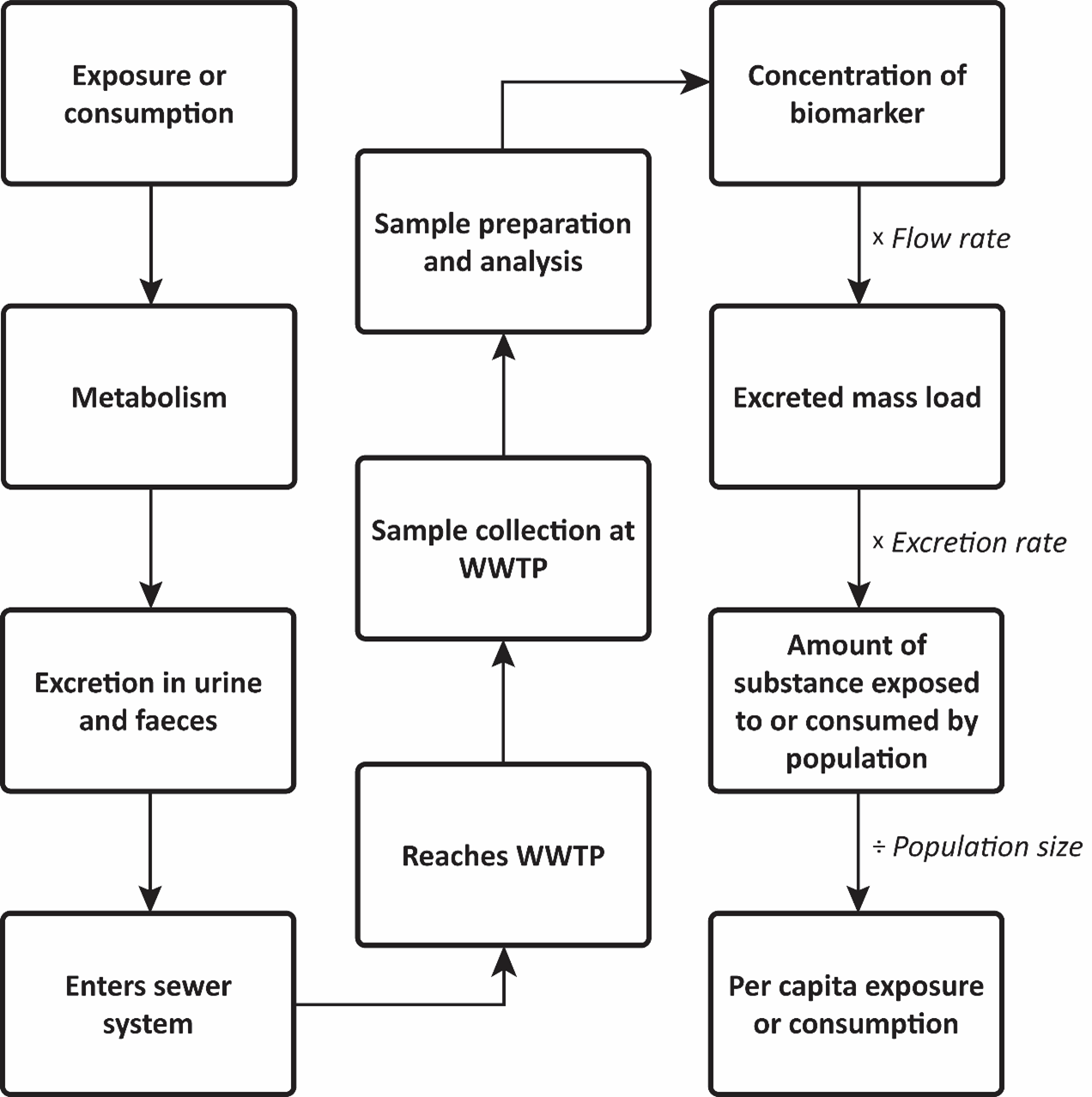

WBE is conceptually simple, yet methodologically complex [Fig. 1]. Throughout the day, people are exposed to a range of substances. Some voluntarily, like food and pharmaceuticals, and others involuntarily, like pollutants and pathogens. Once exposed, these substances are metabolised in the body and excreted through urine and faeces, which then enter the wastewater system. By collecting and analysing wastewater samples, scientists can detect small chemical and biological markers of human health and behaviour, known as biomarkers. By factoring in excretion rates, dosages, and the number of people connected to a wastewater network, per capita levels of exposure or consumption can be estimated across a population.

What began in the early 2000s as a small-scale effort to monitor illicit drug use in a handful of European cities has since grown into a global undertaking. Government agencies around the world now use WBE to track the spread of infectious diseases like COVID-19 [3]. SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) can appear in wastewater days or weeks before the presentation of clinical cases [4]. Consequently, WBE can provide public health authorities with a crucial early warning of potential community transmission. A smaller number of government agencies have turned to WBE to monitor illicit drug consumption. In Aotearoa, for example, New Zealand Police have been routinely monitoring wastewater across the motu since 2019 for methamphetamine, cocaine, and MDMA (sometimes called ecstasy) [5]. Chances are that your wastewater has been collected and analysed by the New Zealand Police.

WBE is clearly no longer just an academic curiosity. WBE findings can have tangible implications for how public health and individual behaviour are understood, managed, and enforced. Clear ethical implications therefore exist surrounding how the data are collected, protected, and acted upon. In this article, I explore some of the ethical risks stemming from the growing involvement of public and private institutions in WBE performance.

Figure 2: Schematic map of a wastewater catchment. Differently shaded areas represent discrete sub-catchments or neighbourhoods that can be individually sampled.

The common practice by academic and government institutions to protect group-level privacy for small sites has been to anonymise the name and location of sampling sites [16]. However, such an approach has not always been appropriate for COVID-19 surveillance, given the importance of fully informing the public about the presence of COVID-19 in the community so that they can act appropriately.

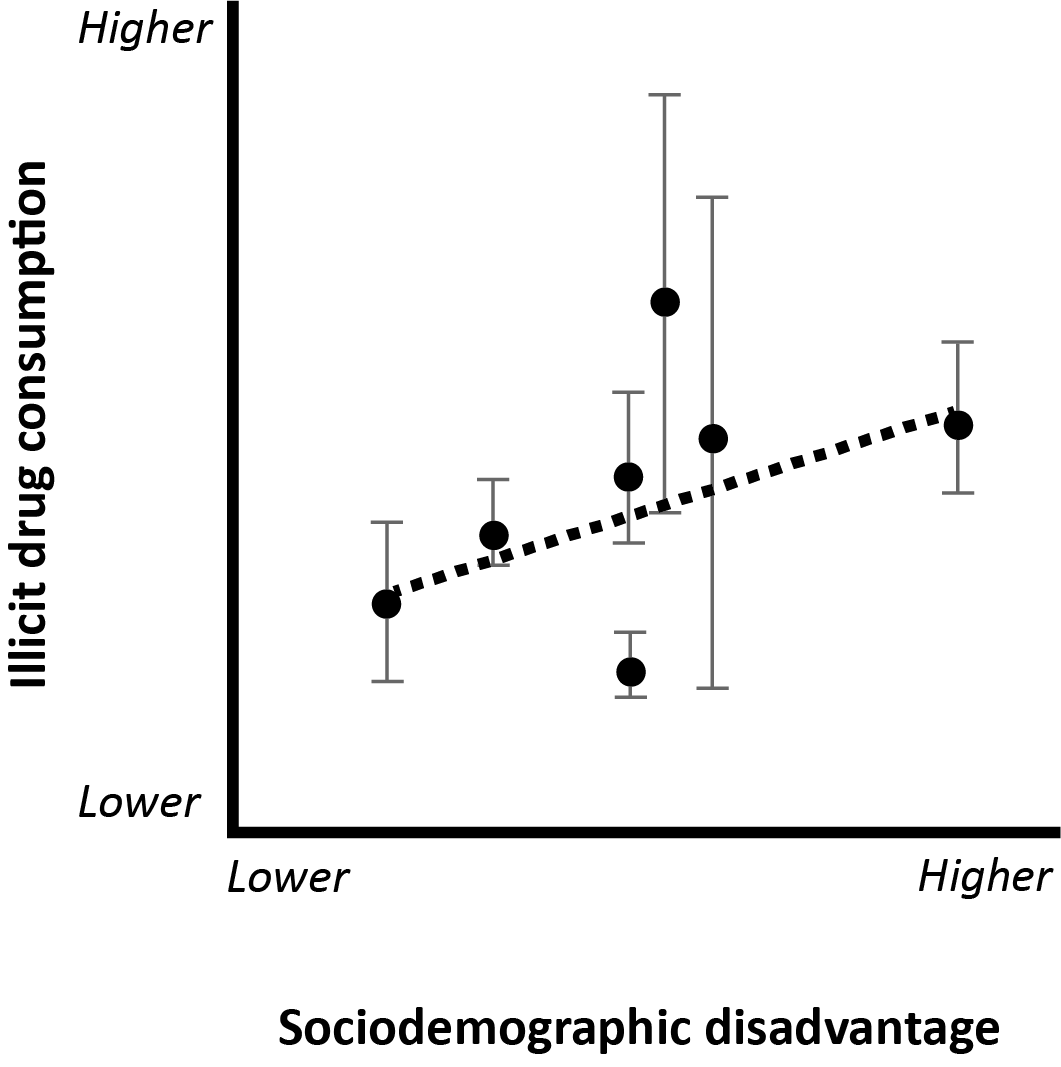

Compounding the issue of group-level privacy and harms is the growing trend of WBE studies combining wastewater data alongside sociodemographic information. These studies typically correlate drug consumption rates or levels of infectious disease (measured via WBE) with the average sociodemographic characteristics of individuals within the wastewater catchments [Fig. 3]. This is often done to identify sociodemographic disparities or to contextualise differences in wastewater data between communities. Although researchers have been careful to phrase such findings as correlations, and not causations, the presentation of wastewater data alongside sociodemographic information can inadvertently fuel damaging narratives that individuals characterised by various sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., ethnicity, poverty, etc.) are responsible for stigmatised behaviours and/or poor health [17].

If wastewater data are presented alongside and associated with sociodemographic information, then the anonymisation of sampling locations matters little. This is because group-level harms can ultimately affect all members of such groups [19]. This is not a hypothetical problem. For example, in August 2021, announcements from the government that over 50% of new COVID-19 cases in Tāmaki Makaurau were of Pacific ethnicity were followed by multiple reports of vitriolic racism directed at Samoan communities and, more broadly, South Auckland [20]. High-profile reporting of wastewater data alongside sociodemographic information in WBE studies could fuel similar narratives.

Figure 3: Correlation between illicit drug consumption and sociodemographic disadvantage measured across seven wastewater treatment plants in Aotearoa. Black dots represent the mean illicit drug consumption for each site. Grey bars represent the minimum and maximum consumption. The dotted line is the trend line. Data adapted from Price et al. [18].

Uncertain funding provides ideal conditions for privatisation

Funding for WBE has been historically uncertain and transient, which has paved the way for greater involvement of private institutions. The COVID-19 pandemic witnessed significant funding allocated to research institutions and public health agencies to monitor the spread of the virus via WBE. However, as government agencies around the world have declared an end to the emergency phase of COVID-19, funding for these programmes has become uncertain. For example, the United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Wastewater Surveillance System is only funded until 2025, creating significant funding gaps [21]. Closer to home in Aotearoa and Australia, WBE programmes for drug use are funded through criminal confiscations and so are perhaps more insulated from the tumult of public health funding. However, cuts to science funding and subsequent reallocation to ‘commercially-focused science’ announced by Aotearoa’s current coalition government show that such certainty is far from guaranteed [22].

In response to funding insecurity (and, more generally, austerity measures reducing public health funding), public health authorities are increasingly turning to private companies to establish, maintain, or expand existing WBE programs [12]. Most commonly, private companies are contracted to collect or analyse wastewater samples. However, a growing number of for-profit biotechnology private companies, like Biobot Analytics, offer full-service WBE, ranging from wastewater sample collection and analysis through to data interpretation and providing recommendations to stakeholders. The growing involvement of private institutions is reshaping the landscape of WBE and with it the potential nature and scale of ethical risks it poses.

Private companies have signalled an eagerness to move sampling ‘up the pipe’

Private institutions have marketed their services to conduct WBE at discrete spatial scales, which can perpetuate the stigmatisation of vulnerable communities and fuel punitive responses. Interest in conducting WBE at small spatial scales is nothing new. As discussed, academic and public health authorities experimented with sampling wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 at small spatial scales. Interestingly, public institutions have approached small-scale sampling for illicit drugs with a considerable degree of hesitancy. This is for good reason. Sampling at these spatial scales is pragmatically challenging, such as the difficulty of installing sampling devices within small sewer pipes. This hesitancy likely also reflects an appreciation of the clear ethical risks that these small-scale investigations pose.

In contrast, however, some private institutions have recognised small spatial scale sampling as a market opportunity. One anonymous biotechnology scientist interviewed and presented in Arefin et al. said this of WBE: “You look at a population…you don’t really know where it comes from. This is exactly the pinpoint that [our private biotechnology firm] is offering. I think that getting the right…picture of sources and places, and to zoom in for specific locations can really assist in this decision-making process” [12, p. 12]. Indeed, some prisons have contracted private companies to sample their wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 [23]. Biobot Analytics also analysed opioid consumption patterns in small (~7,000 people) neighbourhoods in Detroit [24].

As discussed, the highly localised nature of these applications can stigmatise communities and infringe on individual privacy. Of particular concern is where small-scale WBE applications could inform punitive law enforcement practices in prisons, immigration detention centres, and airports. In the current U.S. political climate, it is not difficult to see how WBE performed at immigration detention centres could fuel and reinforce anti-migrant rhetoric espoused by Donald Trump. Detections of infectious disease markers in wastewater (i.e., monkeypox, hepatitis, or other novel viruses) at detention centres could provide the ammunition for authorities to turn away asylum seekers and other migrants. This is not some hypothetical Orwellian future. During the COVID-19 pandemic, under Title 42 of U.S. Code § 265, the Trump administration used the perceived threat of communicable disease as justification to expel asylum seekers and other migrants arriving at U.S. borders without prior authorisation [25]. Although Title 42 is no longer in effect, Trump’s administration has indicated a keen desire to reinvoke this authority, with White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller citing “severe strains of the flu, tuberculosis, scabies, other respiratory illnesses like R.S.V. and so on, or just a general issue of mass migration being a public health threat and conveying a variety of communicable diseases” [26]. It is not difficult to see how privately driven WBE conducted at these politically charged sites could lead to such futures.

Conclusion

WBE is clearly not free from ethical risks, and the growing involvement of private companies with an aptitude to move sampling ‘up the pipe’ may exacerbate many of these issues and raise new concerns surrounding how such data are used.

In response to these concerns, some have advocated for community-based WBE models, where those who are the subject of surveillance have meaningful input into the decision-making process at all stages of WBE, ranging from what questions WBE is seeking to achieve, who retains ownership of the data, and, importantly, how the data will be used [27]. In a similar vein, Indigenous data sovereignty has emerged as a lens to reconsider how data collected on historically overly surveyed communities can remain under the stewardship of such individuals & communities [13].

Regardless of what the future of WBE looks like, be it dominated by public or private institutions (or more likely a mixture of the two), to begin to develop the ethical infrastructure to govern these applications, the fundamental questions we need to ask are “Who decides what we monitor?” and “For whose benefit are these data used?”

Figure 1: Conceptual flow chart of the methodological steps in WBE.

Consent is not required for WBE

Consent is the cornerstone of contemporary research and medical practice. Before participating in a study or undergoing treatment, individuals must be informed of the potential risks and harms and be given the opportunity to freely decline.

However, informed consent is not required in WBE. The logic is that because material is not taken directly from individuals, they remain anonymous and therefore unlikely to be exposed to potential harms [6]. As a result, institutional ethics approval is typically neither sought nor required in WBE. Furthermore, from a practical perspective, obtaining informed consent from all individuals within a wastewater catchment area (potentially hundreds of thousands of people) is simply unfeasible.

Notions of ownership are inherently linked to consent. People generally have a right to control how their data are used. A loss or relinquishment of ownership may remove the need to obtain consent for such information to be collected. Legal precedent has reinforced the idea that bodily materials, once discarded, are no longer the property of the individual. This is best exemplified by the 1990 landmark case Moore v. Regents of the University of California, in which the Supreme Court of California ruled that discarded bodily tissue does not remain the property of the individual [7]. The implication for WBE is that once you flush the toilet, you arguably relinquish the rights to what was flushed. Consequently, wastewater utilities companies are largely responsible for granting permission to perform WBE, not the individual communities they serve.

The hidden nature of sewage infrastructure further reinforces this perspective. In his book, History of Shit, French psychoanalyst Dominique Laporte argues that the development of modern sewers further transformed urine and faeces into something of ill-value, foreign to the body and, therefore, something in need of removal [8]. Today, this ‘flush-and-forget’ mentality surrounding waste underpins the socially uncontested practice of wastewater sampling [9].

The lack of consent in WBE heightens ethical risks

The lack of consent required for WBE raises several concerns. Academic and government institutions rely on a social licence to conduct WBE— namely, public trust and acceptance. If communities feel monitored without their input or fear potential harms, they may withdraw their support. A lack of meaningful consultation with those under surveillance may undermine support for WBE and trust in those conducting it. Furthermore, the lack of formal guidelines to obtain informed consent and institutional ethical oversight may open the door to abuse by academic, state, and private interests. As Boyd and Crawford remind us, “Just because it is accessible does not make it ethical” [10, p. 671].

Gauging and responding to community values is tricky

The lack of consent required for WBE means that there are limited opportunities for those under surveillance to voice their concerns. In response to these issues, some have suggested that WBE practitioners should try to “ensure that their work engages with and is cognisant of community concerns and values” [11, p. 7]. While laudable, defining a ‘community’ is messy. Wastewater catchments are largely fixed in place, but people are not. Workers, tourists, and students flow in and out of wastewater catchments, and so the people physically present within a community can change. Beyond the pragmatics of determining who comprises a community is the fundamental question of whose values are considered [12]. Marginalised and minority voices are more likely to be excluded from conversations about community values. This is problematic as different groups may view the risks of WBE in very different ways. For example, communities historically subjected to state surveillance, such as Indigenous communities or ethnic minorities, may have particular or heightened concerns regarding the risks of WBE, rooted in historical and lived experiences [13].

Stigmatisation of small, marginalised communities—the elephant in the sewer

WBE has typically been considered a ‘low-risk’ form of surveillance because wastewater sampling has historically been conducted at wastewater treatment plants (which can serve hundreds of thousands of people). As such, findings theoretically cannot be tied back to individuals or even specific neighbourhoods. However, growing application of WBE at small spatial scales exacerbates the risk of stigmatisation.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we witnessed interest in targeted WBE in high-risk areas such as discrete neighbourhoods, universities, hospitals, and travel hubs to identify infection clusters [Fig. 2], [14]. The development of small passive samplers (which require less space than traditional automated samplers) is only making surveillance at these small scales more feasible [15]. The ethical risks at this scale are clear. If the findings of WBE can be tied back to specific communities, neighbourhoods, or buildings, this can perpetuate discrimination and stigmatisation.

[1] A. R. George, “On Babylonian lavatories and sewers,” IRAQ, vol. 77, pp. 75–106, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1017/irq.2015.9.

[2] World Health Organization. “Drinking Water.” who.int. https://www. who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water (accessed July 7, 2025).

[3] C. C. Naughton et al., “Show us the data: global COVID-19 wastewater monitoring efforts, equity, and gaps,” FEMS Microbes, vol. 4, pp. 1-8, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1093/femsmc/xtad003.

[4] M. Kumar et al., “Lead time of early warning by wastewater surveillance for COVID-19: Geographical variations and impacting factors,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 441, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.135936.

[5] New Zealand Police, “National drugs in wastewater testing programme – 2024 Annual Overview.” police.govt.nz. https://www. police.govt.nz/about-us/publication/national-drugs-wastewatertesting-programme-2024-annual-overview (accessed July 7, 2025).

[6] W. Hall et al., “An analysis of ethical issues in using wastewater analysis to monitor illicit drug use,” Addiction, vol. 107, no. 10, pp. 1767–1773, Mar. 2012, doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03887.x.

[7] Moore v. Regents of the University of California, 51 Cal. 3d 120, 793 P.2d 479, 1990. Available: https://www.courtlistener.com/ opinion/2608931/moore-v-regents-of-university-of-california/.

[8] D. Laporte, History of Shit, R. el-Khoury and N. Benabid, Transl., Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2000.

[9] T. Scassa, P. Robinson, and R. Mosoff, “The Datafication of Wastewater: Legal, Ethical and Civic Considerations,” Tech. Reg., vol. 2022, pp. 23–35, Feb. 2022, doi: 10.71265/aa9cwm40.

[10] D. Boyd and K. Crawford, “Critical questions for big data: Provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon,” Inf. Commun. Soc., vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 662–679, May 2012, doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

[11] Canadian Water Network, “Ethics and communications guidance for wastewater surveillance to inform public health decision-making about COVID-19,” cwn-rce.c. https://cwn-rce.ca/wp-content/ uploads/COVID19-Wastewater-CoalitionEthics-and-Communications-Guidancev4-Sept-2020.pdf (accessed July 7, 2025).

[12] M. R. Arefin and C. Prouse, “Urban political ecologies of sewage surveillance: Creating vital and valuable public health data from wastewater,” Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr., Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1111/tran.12732.

[13] D. Cormack and T. Kukutai, “Indigenous peoples, data, and the coloniality of surveillance,” in New Perspectives in Critical Data Studies: The Ambivalences of Data Power, A. Hepp, J. Jarke, and L. Kramp, Eds., Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030- 96180-0_6.

[14] D. Schmiege et al., “Small-scale wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) for infectious diseases and antibiotic resistance: A scoping review,” Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health., vol. 259, June 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2024.114379.

[15] R. Verhagen et al., “Exploring drug consumption patterns across varying levels of remoteness in Australia,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 903, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166163.

[16] J. P. Prichard et al. “SCORE ethical research guidelines for sewage epidemiology.” Sewage Analysis Core group Europe. https://www.euda.europa.eu/drugslibrary/ethical-research-guidelineswastewater-based-epidemiology-andrelated-fields_en (accessed July 7, 2025).

[17] M. Price and S. Trowsdale, “The ethics of wastewater surveillance for public health,” J. hydrol., N. Z., vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 59–75, 2022. Available: https://www.hydrologynz. org.nz/journal/volume-61-2022.

[18] M. Price et al., “Spatial, temporal and socioeconomic patterns of illicit drug use in New Zealand assessed using wastewater-based epidemiology timed to coincide with the census,” N. Z. Med. J., vol. 134, no. 1537, pp. 11–26, June 2021. Available: https://nzmj.org.nz/journal/ vol-134-no-1537/spatial-temporal-andsocioeconomic-patterns-of-illicit-druguse-in-new-zealand-assessed-usingwastewater-based-epidemiology-time.

[19] B. D. Mittelstadt and L. Floridi, Eds. The Ethics of Biomedical Big Data, 1st ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2016, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319- 33525-4.

[20] E. Pickering-Martin. “Here we go again: Covid and racism.” E-Tangata. https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/here-we-go-againcovid-and-racism/ (accessed July 7, 2025).

[21] T. Ibitoye and N. Bristol. “Pandemic Center Brief: National Wastewater Surveillance.” Brown University School of Public Health. https:// pandemics.sph.brown.edu/news/2025-01-23/wastewater-brief (accessed July 7, 2025).

[22] A. Gillies. “Science sector sounds alarm over funding shake-up.” RNZ. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/thedetail/563225/science-sectorsounds-alarm-over-funding-shake-up (accessed June 2025).

[23] WaterWorld. “Oklahoma prisons pilot rapid-test wastewater monitoring for Covid-19.” waterworld.com. https://www.waterworld. com/drinking-water-treatment/potable-water-quality/pressrelease/14207731/oklahoma-prisons-pilot-rapid-test-wastewatermonitoring-for-covid-19 (accessed July 2025).

[24] N. Endo et al., “Rapid assessment of opioid exposure and treatment in cities through robotic collection and chemical analysis of wastewater,” J. Med. Toxicol., vol. 16, pp. 195–203, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1007/ s13181-019-00756-5.

[25] D. N. Obinna, “Title 42 and the power to exclude: Asylum seekers and the denial of entry into the United States,” Politics Policy, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 508–523, June 2023, doi: 10.1111/polp.12542.

[26] C. Savage, M. Haberman, and J. Swan. “Sweeping raids, giant camps and mass deportations: Inside Trump’s 2025 immigration plans,” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/11/us/politics/ trump-2025-immigration-agenda.html.

[27] T. Sabo-Attwood, D. A. Bowes, and J. H. Bisesi, “Integrating community perspectives to enhance the utility of wastewater-based epidemiology for addressing substance use in the United States,” Curr. Opin. Psychiatry, May 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/ yco.0000000000001016.

Mackay is a fourth-year PhD student who is interested in using wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) to measure and understand public health. Mackay’s PhD research focusses on refining the methodologies underpinning WBE.