Entropy on Earth

Thermodynamics and Climate Change | Zoe Congalton

What is entropy?

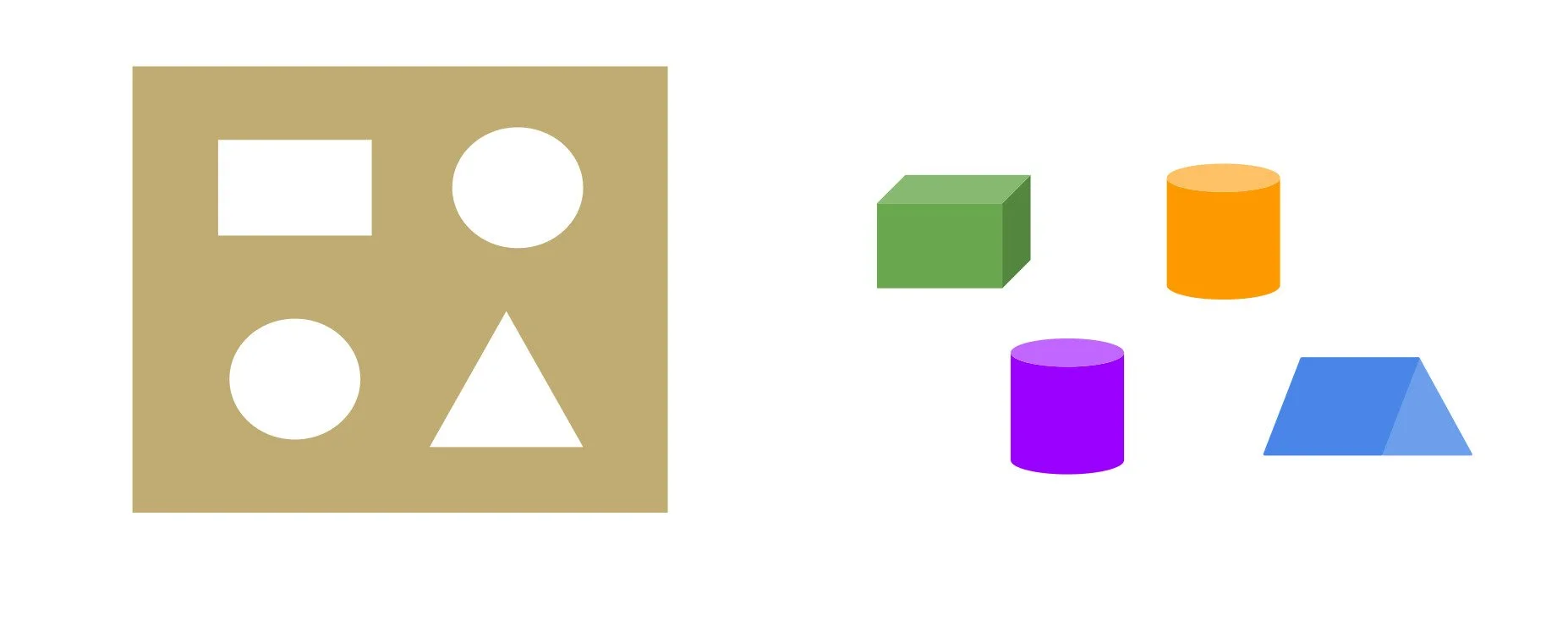

Some have never heard the word, while for others, the concept is foggy and misinformed. It doesn’t help us that entropy has three main definitions, each relevant and true in its own right. Let’s start on the smallest scale. Entropy is a measure of the number of microstates available to distribute energy, describing an overall macrostate [1]. The best way to understand this is with an analogy. Cast your mind back to your baby days, when you were playing with those wooden shape sorting toys. The wooden blocks here represent energy packets, and the slots are molecules.

Figure 1: Visualising a multiplicity of one.

In this state, every block has a designated slot; there is only one possible arrangement. We call this multiplicity one. What if we replaced the half circle with another circle?

Glossary

ATP: a molecule carrying chemical energy within a living organism, produced from metabolising food.

Denature: when a biological molecule loses its structure and breaks apart.

DNA: a double-stranded, long-chain molecule (polymer) containing genetic information in living organisms.

Equilibrium: the state at which change in the forward direction is equal to change in the reverse direction, so that there is no net change over time.

Infrared: electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength larger than visible light, about 800 nm to 1 mm.

Mechanical work: energy transfer resulting in things moving.

Multiplicity: the number of possible arrangements.

Photons: packets of light.

Quasi-equilibrium: changing slowly enough to be considered at equilibrium.

RNA: a single-stranded, long-chain molecule (polymer) containing genetic information in living organisms.

Spontaneous: occurring without continuous input of energy.

Surroundings: the rest of the universe.

System: a specific region of the universe being considered.

UV spectrum: the region of the electromagnetic spectrum with wavelengths smaller than visible light, about 10 nm to 400 nm.

Let’s see how many possible arrangements we’d have…

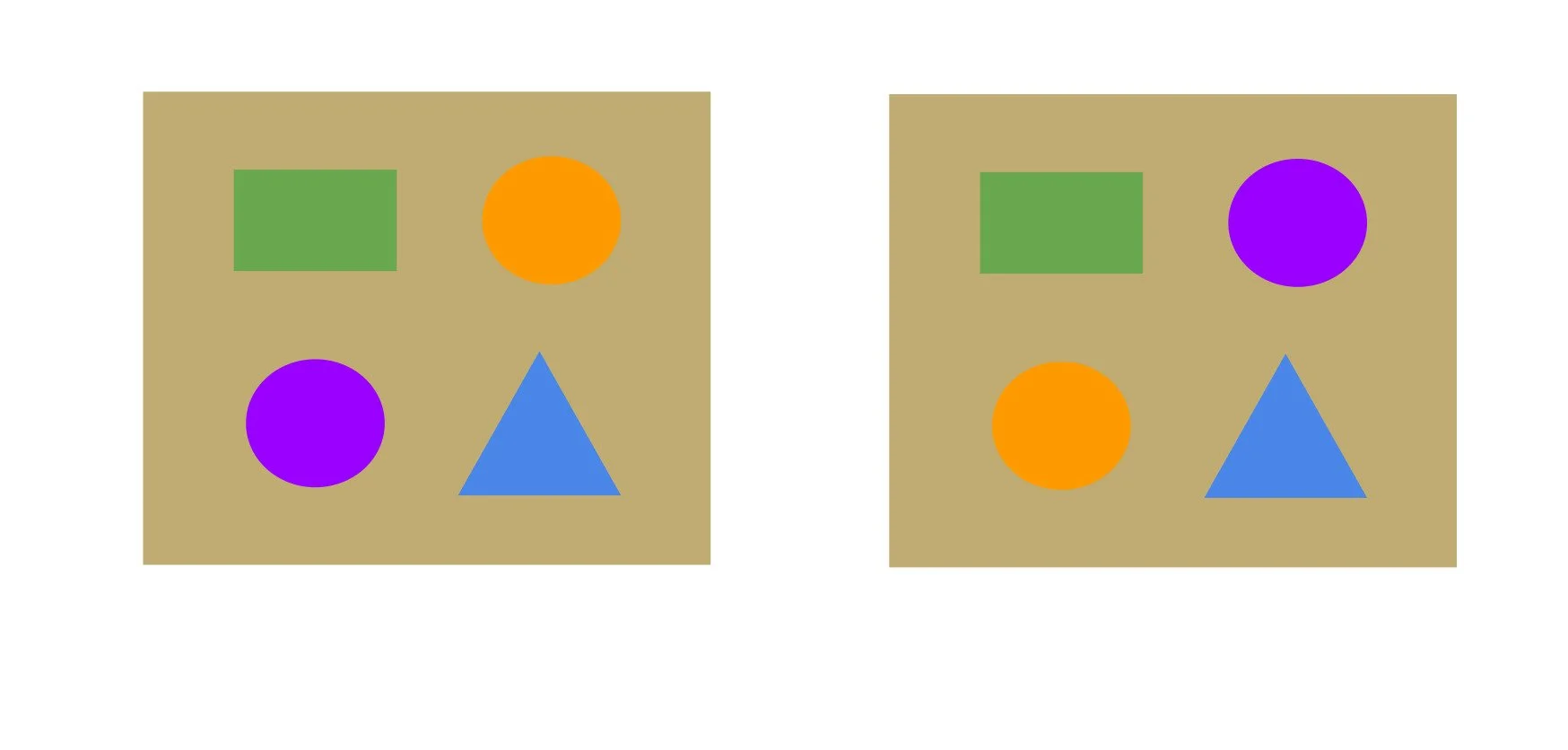

Figure 5: Visualising higher multiplicities (part 2)

Well, that escalated pretty quickly. We now have 4! (4×3×2×1) possible combinations, or 24 as pictured above. For an arrangement with W possible microstates, the equation S = k log W quantifies the entropy (S), where k is Boltzmann’s constant. This concept is what causes entropy to be misinterpreted as disorder. While more possible arrangements don’t inherently define disorder, we tend to associate the two in our consideration of entropy.

This also gives rise to the idea that entropy is the spread of energy. With more microstates to disperse the energy, it makes sense to think of it as more ‘spread out’. This will help later on when we apply entropy to the more complex exchanges on our planet.

To get a general idea of entropy in the world, let’s consider some examples of what increases entropy in our daily lives. Heating makes particles faster, allowing them to occupy more microstates and hence increases entropy. Gas expanding and filling free space, like letting air out of a balloon, increases entropy. Mixing liquids means each molecule has more possible arrangements, which, again, increases entropy.

Another definition of entropy is a measure of spontaneity. The second law Climate Change of thermodynamics states that: All spontaneous changes cause an increase in the entropy of the universe. That is, ∆Suniverse > 0, or change (∆) in entropy (S) is larger than 0 [2].

The universe is a big place, so we normally think about this in localised entropy changes, where we define a system and its surroundings and sum the entropy change of the two. Total entropy must increase. That’s why we can freeze water, which decreases the entropy of the system but increases it in the surroundings.

Finally, we come to the definition of entropy derived from the thermodynamic concept of heat engines. This was the first way entropy was ever considered, and how it got its name [3]. In thermodynamics, heat is a type of thermal energy that is transferred due to a difference in temperature. Typically, when this transfer occurs, the heat is dissipated in the surroundings. But what if the heat energy could be used to do mechanical work? This was a question Clausius asked himself in the 1800s. He tested this by operating a heat engine with a hot reservoir transferring heat energy into work and a cold reservoir to deposit the remainder. He found that at different temperatures, the work he could achieve varied for the same amount of heat transfer. From this discovery, he introduced entropy to keep track of the usefulness and defined it as ∆S = ∆Q/T for any process with a heat transfer of ∆Q at a temperature of T. This encourages us to consider entropy as a measure of energy available to do work. It also supports the idea that not only the quantity of energy transfer is important, but also the quality of energy delivered in that transaction.

So if the overall entropy of the universe must always increase, what does our future look like? Our understanding of thermodynamics reveals that as irreversible processes continue to occur, energy spreads out and becomes less usable over time. If things continue as they are, the second law predicts some eventual heat death of the universe as we know it. A scary thought, but it’s unlikely to come to fruition anytime soon. What is more worrying in the foreseeable future is the irreversible entropy increase on Earth. Let’s go back in time, trace our entropic steps, and consider the complex exchanges of entropy on Earth.

Earth as a heat engine

Four and a half billion years ago, the Earth emerged along with the rest of our solar system (another interesting entropy exchange we won’t get into today). Ever since, the sun has radiated down on Earth, delivering around 9,000,000,000,000 joules of energy every second [4]. An iPhone 16 is able to store around 60,000 joules of energy [5], so this is the equivalent of charging 150,000,000 iPhone 16s every second. Sounds too good to be true! It is. Most of the energy is radiated back into space. Does this ring any bells? It’s the same concept as the heat engine introduced earlier. The energy comes from a hot reservoir (the sun), does work (atmosphere and ocean circulation), and then the leftover is deposited into a cold reservoir (space). What’s crucial is the relation ∆S = ∆Q/T. Heat energy (Q) comes from the sun’s surface at a temperature of around 5,500°C, and around the same amount is radiated into space at an effective emission temperature below zero. So the energy we get from the sun is delivered in low-entropy, useful, high-quality packets (via photons of light), and the Earth emits energy as high-entropy, spread-out, infrared radiation.

Like all real heat engines, Earth isn’t perfectly efficient. You can imagine the operational parts of an engine all moving and creating friction. Wind, for example, creates this frictional dissipation, along with the movement of the oceans [6]. Another critical energy loss is through the water cycle.

Heating, evaporation, and mixing of water in the atmosphere are processes that increase entropy. Nonetheless, this cyclic gain and loss of heat was stable. It is ultimately what enabled the existence of liquid water, setting the stage for the origin of life on Earth.

Entropy of life

If we think about our view of entropy so far, the emergence of life on Earth is puzzling. How would such ordered structures spontaneously form? The unsatisfying answer is that we don’t know for sure. Life is reliant on the replication of complex DNA and RNA molecules, an intricate process involving decreasing entropy that will not happen spontaneously. Most life today uses molecules that provide usable energy, like ATP, to do so. This organised energy is consumed by enzymes in cellular processes such as replication. Life can therefore exist, as in order to do so, it creates a net increase of entropy in the universe.

A likely explanation is that RNA emerged because it increased entropy within the conditions present on Earth at the time [7]. The surface was hot, and the atmosphere was thick with sulfur dioxide clouds from volcanic eruptions. Sounds awful, I know, but the RNA loved it. It turns out the five nucleic acids that make up DNA and RNA—adenine, thymine, cytosine, guanine, and uracil—absorb in the UV spectrum. At the time, the only sunlight that could get through the thick atmosphere was a particular range in the UV spectrum, matching perfectly with the maximum absorption of the nucleic acids. When a molecule absorbs light, it is excited; it vibrates, rotates, and dissipates that energy, increasing entropy. As a result, these molecules are more likely to emerge spontaneously from natural chemical reactions.

The heat and UV also provided ideal conditions for reactions between small molecules to form longer chains, called polymerisation. Double-stranded polymers that had formed would not survive the hottest hours of the day, causing them to denature, sometimes cleaving in the middle to form two identical single strands. During the cool night, the cleaved halves would each go on to rebuild their double-stranded structure. This would lead to two copies of the original strand, the very first replication of DNA!

Entropy of evolution

At this stage, it is important that we review our understanding of entropy, not as disorder, but as a measure of microstates. Evolution is a phenomenon that has tripped up many, as it appears to violate the second law of thermodynamics. How can we have moved towards more intelligent and adapted life forms without decreasing entropy? Perhaps we need a clear definition of what Darwin proposed as evolution. It refers to the tendency of individuals to have more offspring when they are better able to survive and reproduce in the environment.

This causes certain features to be favoured over time. It’s how we humans—and the species we share our planet with—are here today. Although it may seem at first glance to violate the second law, the principle of evolution is not that life becomes more complex [8]. In fact, horses have evolved to have one toe from five, and ostriches have evolved two toes from four!

Human impact on entropy

Up until recently, Earth facilitated a slow biological evolution, gradually increasing in entropy, but sustainable enough for many more billions of years [9]. We can think of the early Earth as an entire system in quasi-equilibrium. Although there were many processes occurring, on a large scale, the state of the system was approximately constant. This ended with Homo sapiens. Early humans’ ability to control fire was the spark that ignited our ever-growing appetite for energy. Their developing ability to communicate and pass on knowledge ceased the slow biological evolution, unleashing an uncontrollable surge in energy production and use.

It is safe to say human evolution has significantly changed the conditions on Earth. Consumption of non-renewable fuels like petrol and coal disrupts the energy balance. These are forms of low entropy, stored energy we can extract from Earth. Burning them, for example, to power a car, causes the energy to be converted into dissipative thermal energy like heat and sound. By doing so, entropy is irreversibly increased. The quasi-equilibrium state the Earth was previously in, receiving energy from the sun and equally dissipating it into space, is sacrificed by this excessive consumption of stored energy.

Renewable energy, like wind and solar, uses only what the Earth previously sustained. It utilises the heat engine we inhabit to provide the energy we live off. It is a miraculous solution that may allow us to bask in the luxury of energy on demand, without spiralling Earth’s entropy out of control. Although this seems like a satisfactory conclusion, unless we can instantaneously switch to fully renewable energy and undo the transpiring consequences, we have a bit of an issue.

Chemical reactions at equilibrium follow a rule called Le Chatelier’s Principle, stating that any change in conditions will cause a system to shift its equilibrium, counteracting this change. It has been suggested that the Earth will act in this way, pushing back against the disruption we’ve caused. So far, we’ve been devastated by heat waves, wildfires, earthquakes, flooding, storms, tsunamis, and other natural disasters. This is predicted to be only the beginning [10]. It is a response of the system we occupy against the upset we inflicted on its sustainable entropy equilibrium. Personally, I’m not so keen on continuing the way we are to see what the Earth fires back next.

Figure 2: Visualising multiplicity of two (part 1)

Now we have two possible arrangements where the purple and orange circle slots are interchangeable. This is a multiplicity of two.

Figure 3: Visualising multiplicity of two (part 2)

What if all four were circles?

Figure 4: Visualising higher multiplicities (part 1)

[1] J. S. Martin, N. A. Smith, and C. D. Francis, “Removing the entropy from the definition of entropy: clarifying the relationship between evolution, entropy, and the second law of thermodynamics,” Evol.: Educ. Outreach, vol. 6, no. 1, Oct. 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1936- 6434-6-30.

[2] Lumen Learning. “Entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics: Disorder and the Unavailability of Energy.” courses.lumenlearning. com. Accessed: August 16th, 2025. [Online]. Available: https:// courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-physics/chapter/15-6-entropyand-the-second-law-of-thermodynamics-disorder-and-theunavailability-of-energy/.

[3] D. Van, “Entropy, the magic ruler?,” Phys. Essays, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 227–230, Jun. 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.4006/0836-1398- 34.2.227.

[4] S. Kabelac and F.-D. Drake, “The entropy of terrestrial solar radiation,” Sol. Energy, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 239–248, 1992, doi: https://doi. org/10.1016/0038-092x(92)90097-t.

[5] Anker. “iPhone 16 Battery Life: Specs Breakdown, Upgrades & Boosting Tips.” anker.com. Jul. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https:// www.anker.com/blogs/power-banks/iphone-16-battery-life.

[6] M. S. Singh and M. E. O’Neill, “Thermodynamics of the climate system,” Phys. Today, vol. 75, no. 7, pp. 30–37, Jul. 2022, doi: https:// doi.org/10.1063/pt.3.5038.

[7] K. Michaelian, “Entropy Production and the Origin of Life,” J. Mod. Phys., vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 595–601, 2011, doi: https://doi.org/10.4236/ jmp.2011.226069.

[8] S. A. Cushman, “Entropy, Ecology and Evolution: Toward a Unified Philosophy of Biology,” Entropy, vol. 25, no. 3, p. 405, Mar. 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/e25030405.

[9] V. K. Dobruskin, “The Planet’s Response to Human Activity. Thermodynamic Approach,” Open J. Ecol., vol. 11, no. 02, pp. 126– 135, Jan. 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.4236/oje.2021.112011.

[10] Z. Kolenda, J. Donizak, A. Takasaki, and J. Szmyd, “Growing Energy Consumption, Entropy Generation and Global Warming,” JSM Environ. Sci. Ecol., vol. 12, no. 2, 2024, Available: https://www.jscimedcentral. com/jounal-article-info/JSM-Environmental-Science-and-Ecology/ Growing-Energy-Consumption.

Zoe is in her second year studying Physics and Chemistry. She is drawn to the mysteries of the universe, but is especially interested in how we can better understand the future of our world amidst a changing climate. She sees science as both powerful and deeply inspiring.