Fish or Cut Bait: EBM Heralds Overdue Change for Commercial Fisheries Management

Ecosystem-Based Management and Fisheries | Keila D’Alia

Tijuana River Mouth State Marine Conservation Area

Metallic, a single leopard shark slithers through estuarine waters near the California-México border soon!

Piedras Blancas State Marine Reserve, 520 kilometres north

Kelp beds sway in what looks like blue Gatorade nearby sparkling tidepools.

Pyramid Point State Marine Conservation Area, 745 kilometres north

A stone’s throw from Oregon, a great blue heron, orange beaked and slender, flies to rocks offshore from a sandy beach.

These sites are just three of the 124 meticulously designed marine protected areas (MPAs) along the California coast in the west of the United States [1, 2]. Separated from one another by hundreds of kilometres, they are fundamental points within the “largest ecologically connected MPA network in the world”, a monumental feat achieved because of the Marine Life Protection Act [3]. Initially passed in 1999, it took nearly a decade and a half to establish a network that could achieve objectives such as [1]:

a. the protection of “the diversity of species that live in different habitats and those that move among different habitats over their lifetime” (through habitat representation);

b. the creation of conditions that “facilitate connectedness …based on known scales of larval dispersal” (through appropriate spacing).

The planning process was largely open to the public, and heavily relied on collaboration between two state agencies, regional and state-level stakeholder groups, and almost 50 scientists from various fields, all under the oversight of a task force. Its successful implementation is now recognised as a significant step forward for Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) [4]. In contrast to single-sector or single-species approaches to natural resource management that do not reflect the complexity of ecosystem function and human use, EBM is a holistic method of natural resource management centered around the best readily available science and communication between stakeholders [1], [4], [5].

But what do Californian MPAs have to do with Aotearoa? Consequently, lessons learned from the Marine Life Protect Act process can provide critical insights for how to manage our marine resources more sustainably. This article will explore the concept of EBM, explaining its necessity in fisheries management, and its place within the context of Aotearoa.

What is EBM?

The Specifics of “Holistic”

While EBM may be implemented differently across vast areas due to its place-based approach, as well as varying definitions, consistent characteristics include [4], [6]–[8]:

The end goal of sustainable natural resource management alongside human use;

Design of law and policy informed by the “best readily available science;”

3. Managers accepting uncertainty, and design being flexible and open to change;

4. Design reflecting ecosystemic complexity by considering elements such as species interactions and movements across habitats;

5. Design reflecting social complexity by embedding stakeholder input, co-governance between different sectors, and Indigenous knowledge and leadership.

Challenges of Implementation

While a multitude of theory surrounding EBM exists, there are several roadblocks that contribute to it being a largely theoretical style of management with practical applications still in their infancy, including [1], [4], [6]–[8].

The time-consuming nature of EBM design, as it requires collaboration between different sectors and subsectors, and considers different uses of the same area;

Heavy financial expenses;

The lack of complete scientific datasets, which is why design can only be informed by the “best readily available science” [4] and must be open to improvements.

Why is there a need for EBM within fisheries management?

London, 1882, Fisheries Exhibition

“I believe, then, that the cod fishery, the herring fishery, the pilchard fishery, the mackerel fishery, and probably all the great sea fisheries, are inexhaustible; that is to say, that nothing we do seriously affects the number of the fish. And any attempt to regulate these fisheries seems consequently, from the nature of the case, to be useless.” [9]

In the time since English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley gave this statement during his inaugural address, the world has seen the decline of countless industrial (large-scale commercial) fisheries. These include the collapse of the Northern cod [10]–[11], Atlanto-Scandian herring [12], Namibian pilchard [13], and Chilean jack mackerel [14] fisheries. That is to say, when overexploitation and mismanagement accompany advancements in fishing technology, fishing yield is seriously affected.

Impacts on the target species aside, habitat and population damage can occur through bycatch and destructive fishing gear [15]. For example, bottom trawling still occurs on a limited scale within the Tīkapa Moana/ Hauraki Gulf [16], physically homogenising ecosystems as the machinery steamrolls the seafloor. The result is a comparatively uniform benthic community, one where only “short-lived, fast growing” [15] organisms have a chance at proliferating. Meanwhile, target species have been documented to experience fisheries-induced evolution in response to overfishing [17]–[18]. By exploiting in a size-selective manner, organisms with undesired traits, such as smaller sizes due to slow growth rates, remain to create the next generation. Target species also adapt by reaching maturation earlier than when unpressured, allowing them to procreate before being fished out, an evolutionary advantage that exacerbates the issue of decreased size. As demonstrated with notable fisheries such as the Northeast Arctic cod and Pacific pink salmon, when whole fish populations evolve to grow slower and reproduce quicker, the biomass yield is reduced [18]. When the yield has reduced enough… Enter: a collapsed fishery.

It is not only the natural ecosystem that suffers from mismanagement. Job insecurity is always a risk. When Captain Elvis Macaya describes the 2011 collapse of the Chilean jack mackerel fishery, he states, “[It] endangered our employment, it was a critical period in which jack mackerel was heavily exploited, both by us and the foreign fleet” [14]. Even prior to fishery collapse, unsustainable exploitation can limit the number of markets available, decreasing the potential for profit. Such is the case for orangy roughy within Aotearoa. Although the Land of the Long White Cloud is a leader in sustainable industrial fishing by global standards, orange roughy management is an area of concern [19]. 46% are caught within non-Marine Stewardship Council certified fisheries [20]. MSC certification is a global signifier of sustainable practice, and is the door-opener to exporting fish to international markets that prioritise selling goods with the “blue tick of approval” [20]. Unsustainable management is not just a biological concern, but a cost that weakens market strength.

The call for a new style of fisheries management comes not just from the shortcomings of current design, but the climatic changes on their way (and in many cases, already here).Talking with Dr. Ali Della Penna, Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Marine Science and School of Biological Sciences, I learned a couple of ways that climate change alters species behavior. The first is through phenology, or the timing of critical events. In marine environments, this can present itself through phytoplankton blooms occurring earlier than normal, resulting in a misalignment of the bloom and arrival of a phytoplankton-eating fish species. “It’s like everyone shows up at the party and the food is already gone”, states Dr. Penna [21]. When determining how much fish to catch, not accounting for these misalignments can mean the end of a fishery. Secondly, shifts in community composition and spatial distribution can occur because different species do not uniformly respond to changes in environmental conditions. For example, increasing temperatures can result in migrations of fish mobile enough to travel hundreds of kilometres to areas they can better thrive. Unfortunately, fisheries quotas do not tend to account for climate-induced migrations and are based on a static idea of where species occur, complicating the process of fulfilling a quota.

The detriments of modern industrial fishing run deeply. But working towards the goals of EBM – ecosystemic and social sustainability – are a potential for positive change alongside that of the climate.

What does EBM look like?

Efforts towards application in Aotearoa through the QMS

Although a comprehensive EBM plan has yet to be implemented in Aotearoa, it can be argued that the formation of and advancements within the Quota Management System (QMS), introduced in 1986, are the first steps towards doing so. “New Zealand’s QMS focuses primarily on the management of individual fish stocks through the setting of total allowable catches (TAC) and total allowable commercial catches (TACC, allocated as ITQ [Individual transferable quotas, a fixed percentage of the TACC]) and is therefore essentially a single species-focused system” [7]. Within the QMS, there are 98 species/species groups, organised into 642 stocks with their own quota management areas (QMAs) [22]. For example, Jasus edwardsii, or kōura papatea, also known as southern/red/spiny rock lobster, can be found all around Aotearoa’s coasts, and is separated into ten fish stocks [23].

While there is certainly room for the QMS to grow in terms of sustainable natural resource management, it does embody EBM principles in some ways, including [7]:

a. Fish stocks statuses are thoroughly investigated on a yearly basis, and the information is synthesised in publicly available stock assessments.

b. Fish stocks are managed according to a soft limit, hard limit, overfishing threshold, and management target.

c. Management attempts to reflect natural variation in fish stocks by the transition of ITQs from fixed to proportional values.

d. Efforts are taken to lessen fishing-related mortality of protected species through sea lion exclusion devices (SLEDs), area closures, and conducting risk. assessments for protected species (such as Maui’s and Hector’s dolphins).

e. Set areas closed to trawling and dredging (methods of commercial fishing).

Theory

EBM is still a highly theoretical concept in the infancy of its application, but there exists a rich amount of theory to help inform future management design. Some frameworks include:

a. The Waka-Taurua (double canoe) framework, with one canoe representing “Māori worldview and values” and the other “broader NZ societal worldviews and values”, sometimes connected to achieve a common goal and others separate [6], [24], [25]

b. Holliday and Gautam’s (2005) three levels of ecosystem approaches, growing from single species focus to multi-species focus to multi-sector approaches [7]

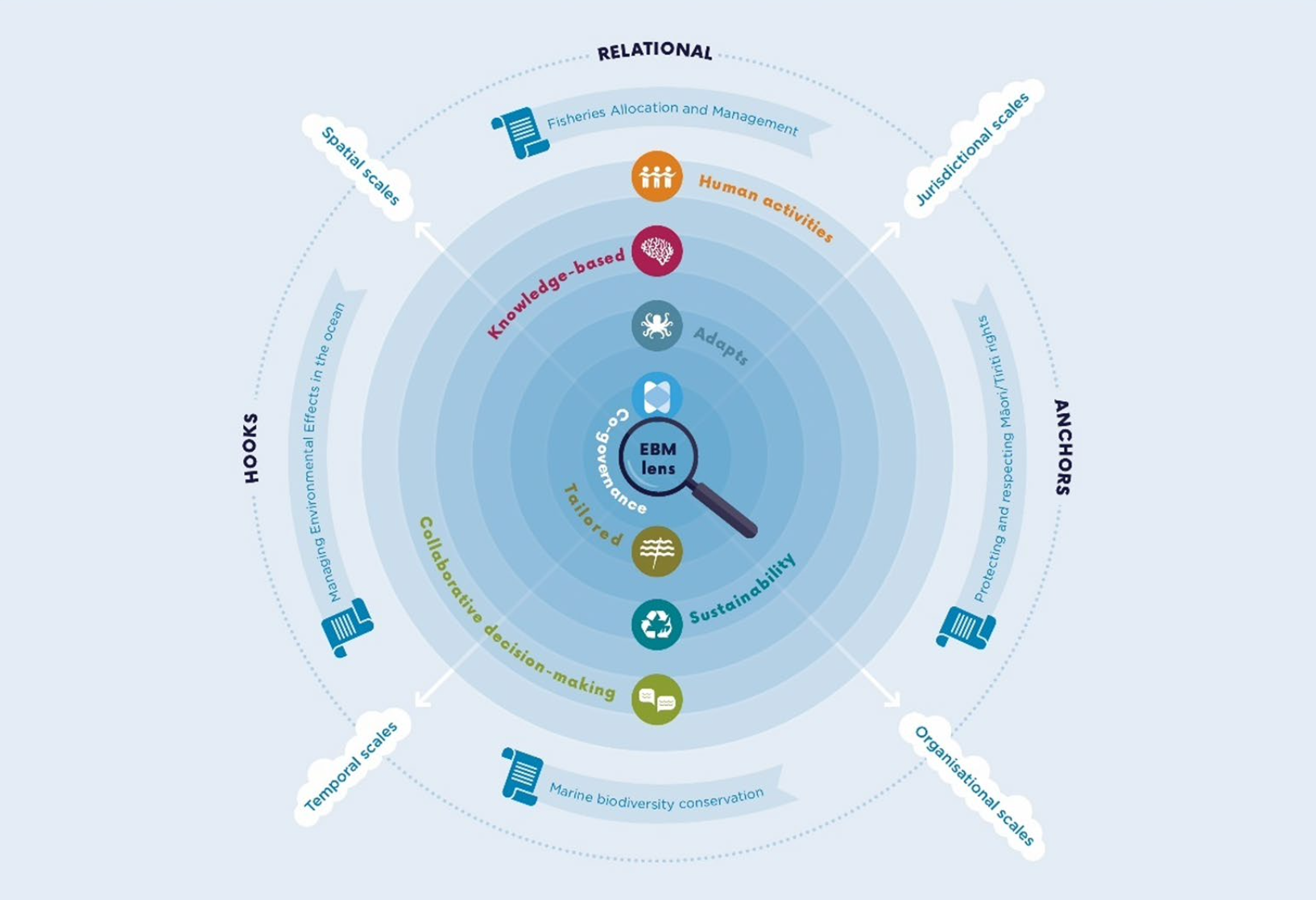

c. The hooks and anchors approach from Macpherson et al. (2021), centered around “hooks” (“rules, tools and processes” supported across sectors) linked to “anchors” (ecological goals) in order to arrive to EBM in a relational way that aligns with Indigenous worldviews and practices [6], [26]

d. The seven principles of EBM by Hewitt et al.: human activities, knowledge-based, adapts, co-governance, tailored, sustainability, and collaborative decision-making [6]

The challenges that come with properly managing our fisheries as the oceans change is largely due to webs of stakeholder and ecosystemic relationships. No small feat indeed. But the potential for Aotearoa to become even more of a world leader in natural resource management means moving away from oversimplistic design to one that embraces the reality of complex relationships between science, society, and the environment.

Figure 1: Designed by Macpherson, et al. [6], this model conceptualised the potential for marine EBM within Aotearoa across different scales, and draws from the “hooks”/“anchors” approach and Hewitt et al.’s seven principles.

Glossary

Hard limit: Stocks fished past this limit are collapsed.

Management target: The level around which we aim to fish stocks in order to exploit them sustainably, allows for fluctuations.

Mātaitai: reserves managed by tangata whenua that allow for customary fishing.

Overfishing threshold: The percentage of the fish stock that cannot be removed, or else the stock will start to fall under other levels.

Rāhui: a Māori practice of prohibition of area usage to allow for regrowth. It could also be placed on an area that is tapū to allow for the dissipation of negative spiritual energy, for example after a death.

Soft limit: Stocks fished past this limit are overfished.

Taiāpure: local fisheries managed by the community and government. They are significant to local hapū or iwi, and allow for all types of fishing (with recommendations from the local community).

Figure 2: Kōura papatea (Jasus edwardsii) in Anchor Bay along the Tāwharanui Peninsula, by Shaun Lee. [32]

The Case of Kōura Papatea: A Prediction for Future EBM Within Aotearoa

In figuring out what “area” to next tackle when applying EBM to commercial fisheries in Aotearoa, we do not need to look far. One direction would be to venture in that of kōura papatea. According to Tini a Tangaroa/Fisheries New Zealand, this marine crayfish “supports the most valuable inshore commercial fishery in New Zealand,” with the sum of its exports in 2021 totalling to NZD$329 million [23]. A tāonga species, the sustainable exploitation of kōura matters to a number of stakeholders, including customary, commercial, and recreational fishers [23, 27]. Marine kōura fisheries are strictly managed under the QMS [27-29]. However, after analysing marine heatwave (MHW) patterns around Aotearoa as part of my MARINE 399 capstone in Semester 1, I predict that the application of EBM principles will be necessary to ensure the long-term viability of marine kōura.

The capstone, advised by Associate Professor of Marine Science, Dr. Nick Shears, aimed to answer the question: “How do recent warming events compare between the Leigh and Portobello regions in Aotearoa?” Statistical and MHW analyses of long-term sea surface temperature (SST) datasets provided by the Leigh (LML) and Portobello Marine Laboratories (PML) were conducted. There are ten commercial marine kōura fisheries nationwide; LML (North Island, northeast coast) sits within the CRA2 fishery, near the CRA1 and CRA2 border, and PML (South Island, southeast coast) sits within CRA7. Some statistically significant findings from the capstone include:

a. Leigh Marine Laboratory (1 January 1967 - 19 December 2024): i. Long-term seasonal warming in autumn and winter ii. Long-term monthly warming for February - June, and August

b. Portobello Marine Laboratory (1 January 1953 - 31 December 2024): iii. Long-term seasonal warming for all four seasons iv. Long-term monthly warming for April - September v. Highest rate of long-term monthly warming experienced in July vi. MHW events are occurring more frequently and at higher intensities

c. Both vii. Increases in the mean annual SST viii. Increases in the duration of MHW events

Phenologically, one reason these findings are alarming is that kōura mating occurs from April to July [30], and how warming during this critical period will impact yield is unknown within the context of NZ. Not only will these warming trends affect kōura behavior and characteristics, but it will reshape its habitat conditions and species interactions, direct and indirect. It is crucial to consider that this study only found warming within CRA 2 and CRA7 fisheries because the available datasets were from these regions, and the possibility that warming is occurring in any of the other eight fisheries should not be discounted. In order to continuously exploit kōura papatea, an adaptable, climate science-informed approach must be taken.

Under the QMS, comprehensive stock assessments are already key in determining catch allowances. But sustainably managing fisheries cannot mean managing species in isolation or attempting to protect them with insufficiently-sized marine reserves that do not account for mobility (as is the case with multiple reserves in NZ) [31]. It requires monitoring on how habitats, critical biological periods, behavior, and species interactions are changing with the climate to best determine its catch allowances and those of related species. It will rely on Indigenous leadership, and techniques from mātauranga Māori – including mātaitai, rāhui, and taiāpure – to be used alongside scientific tools like modelling. It will uphold the values of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

[1] Saarman, E., Gleason, M., Ugoretz, J., Airamé, S., Carr, M., Fox, E., Frimodig, A., Mason, T., & Vasques, J. (2013). The role of science in supporting marine protected area network planning and design in California. Ocean & Coastal Management, 74, 45–56. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.08.02

[2] California marine protected areas (MPAs). (n.d.). https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/ Marine/MPAs

[3] About California’s MPAs. (n.d.). Wildlife. ca.gov. https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/ Marine/MPAs/About

[4] Shears, N. Block 3 Lecture 6 - EcosystemBased Management and Marine Spatial Planning [Slides].

[5] Gleason, M., Fox, E., Ashcraft, S., Vasques, J., Whiteman, E., Serpa, P., Saarman, E., Caldwell, M., Frimodig, A., Miller-Henson, M., Kirlin, J., Ota, B., Pope, E., Weber, M., & Wiseman, K. (2013). Designing a network of marine protected areas in California: Achievements, costs, lessons learned, and challenges ahead. Ocean & Coastal Management, 74, 90–101. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.08.013

[6] Macpherson, Elizabeth, et al. “Designing Law and Policy for the Health and Resilience of Marine and Coastal Ecosystems—Lessons from (and For) Aotearoa New Zealand.” Ocean Development and International Law, vol. 54, no. 2, 3 July 2023, pp. 200–252, https://doi.org/10.1080/00908320.2023.2224116.

[7] Cryer, Martin, et al. “New Zealand’s Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management.” Fisheries Oceanography, vol. 25, no. S1, Apr. 2016, pp. 57– 70, https://doi.org/10.1111/fog.12088.

[8] McLeod, K. L., et al. (21 Mar. 2005) Scientific Consensus Statement on Marine Ecosystem-Based Management..

[9] Huxley, Thomas . “Inaugural Address, Fisheries Exhibition, London (1883).” Aleph0.Clarku.edu, aleph0.clarku.edu/huxley/SM5/fish.html.

[10] Hamilton, Lawrence, and Melissa Butler. “Outport Adaptations: Social Indicators through Newfoundland’s Outport Adaptations: Social Indicators through Newfoundland’s Cod Crisis Cod Crisis.” Human Ecology Review, vol. 8, no. 2, 2001, pp. 1–11, scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?article=1168&context=soc_facpub.

[11] Olsen, E. M., Heino, M., Lilly, G. R., Morgan, M. J., Brattey, J., Ernande, B., & Dieckmann, U. (2004). Maturation trends indicative of rapid evolution preceded the collapse of northern cod. Nature, 428(6986), 932–935. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02430

[12] MSC International. Atlanto-Scandian herring stock driven to critical levels as catches face steep cut by 44%. (2023). https://www.msc.org/ media-centre/press-releases/press-release/atlanto-scandian-herringstock-driven-to-critical-levels-as-catches-face-steep-cut-by-44

[13] Namibian Chamber of Environment. (n.d.). Why the Namibian moratorium on sardine fishing must continue. Conservation Namibia. https://conservationnamibia.com/blog/b2021-sardine-fishing.php

[14] MSC International. Chilean Jack Mackerel: Bust To Boom. (2019). https://www.msc.org/what-we-are-doing/fishery-features/chilean-jackmackerel

[15] Herbert, N. (2024). Fishing and fishing impacts 1: Techniques & Benthic Impact [Slides].

[16] Bevin, A. (2025, May 14). Hauraki Gulf bottom trawling corridor proposals chucked on ice. Newsroom. https://newsroom. co.nz/2025/05/14/hauraki-gulf-bottom-trawling-corridor-proposalschucked-on-ice/

[17] Herbert, N. (2024). Fishing Impacts II [Slides].

[18] Herbert, N. (2024). Fisheries-induced Evolution [Slides].

[19] NZ orange roughy fishery self-suspends part of its MSC certificate. (2023, December 6). Australia & New Zealand; Marine Stewardship Council. https://www.msc.org/en-au/media-centre-anz/news-views/ news/2023/12/06/nz-orange-roughy-fishery-self-suspends-its-msccertificate

[20] From overfished to outstanding: The remarkable sustainability journey of MSC certified orange roughy. (2025, April 23). Australia & New Zealand; Marine Stewardship Council . https://www.msc.org/en-au/ media-centre-anz/news-views/news/2025/04/23/from-overfished-tooutstanding--the-remarkable-sustainabilityjourney-of-msc-certified-orange-roughy

[21] Della Penna, A. (2025, August 26). [Interview by K. D’Alia].

[22] Ministry for Primary Industries. (n.d.). Fish Quota Management System . https:// www.mpi.govt.nz/legal/legislation-standardsand-reviews/fisheries-legislation/quotamanagement-system/#about

[23] Webber, D. N., Roberts, J., Pons, M., Rudd, M. B., & Starr, P. J. (2025). Operational management procedures for New Zealand rock lobster (Jasus edwardsii) in CRA 7 and CRA 8 for 2025–26 [Review of Operational management procedures for New Zealand rock lobster (Jasus edwardsii) in CRA 7 and CRA 8 for 2025–26]. Tini a Tangaroa . https://www.mpi. govt.nz/dmsdocument/68622-FAR-202519- Operational-management-procedures-forNew-Zealand-rock-lobster-Jasus-edwardsiiin-CRA-7-and-CRA-8-for-202526/

[24] Stronge, D., Edwards, P., & Kannemeyer, R. (2023). A Waka-Taurua social licence to operate framework [Review of A Waka-Taurua social licence to operate framework]. Manaaki Whenua. https://ourlandandwater.nz/wpcontent/uploads/2024/02/LC4389_WakaTaurua-SLO-framework.pdf

[25] Maxwell, K. H., Ratana, K., Davies, K. K., Taiapa, C., & Awatere, S. (2020). Navigating towards marine co-management with Indigenous communities on-board the WakaTaurua. Marine Policy, 111, 103722. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103722

[26] Macpherson, E., Urlich, S. C., Rennie, H. G., Paul, A., Fisher, K., Braid, L., Banwell, J., Torres Ventura, J., & Jorgensen, E. (2021). “Hooks” and “Anchors” for relational ecosystembased marine management. Marine Policy, 130, 104561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. marpol.2021.104561

[27] Tini a Tangaroa. (2023). Review of sustainability measures for spiny rock lobster (CRA 3) for 2024/25 [Review of Review of sustainability measures for spiny rock lobster (CRA 3) for 2024/25]. https://www. mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/60475-Reviewof-sustainability-measures-for-spiny-rocklobster-CRA-3-for-202425-Discussiondocument/#:~:text=3.3.1%20CRA%203%20 management,1%20April%20to

[28] Manatū Ahu Matua. Breen, P. (n.d.). CRA 9 management procedure evaluations: New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2014/20 [Review of CRA 9 management procedure evaluations: New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2014/20]. https://www.mpi. govt.nz/dmsdocument/4364/direct/

[29] Tini a Tangaroa. (n.d.). Māori customary fishing information and resources | MPI - Ministry for Primary Industries. A New Zealand Government Department. Www.mpi.govt.nz. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/ fishing-aquaculture/maori-customary-fishing/maori-customary-fishinginformation-and-resources/

[30] Southern Rocklobster Limited. Southern Rocklobster Limited. (n.d.). The Life of a Southern Rock Lobster [Review of The Life of a Southern Rock Lobster]. https://southernrocklobster.com/assets/7.-SRL-Life-Cycle.pdf

[31] LaScala Gruenewald, D. E., Grace, R. V., Haggitt, T. R., Hanns, B. J., Kelly, S., MacDiarmid, A., & Shears, N. T. (2021). Small marine reserves do not provide a safeguard against overfishing. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.362

[32] Lee, S. Southern Rock Lobster (Jasus Edwardsii). iNaturalist. [Photo]. Available: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/8462543

Keila D’Alia recently graduated with a BSc in Marine Science/BGlobalSt in Global Environment and Sustainable Development conjoint, and plans to pursue a PGDip in Marine Science next year. Her love of the ocean is expressed through her academic interests (marine ecology, climate change) and perpetual keenness for a surf.

Keila D’Alia - BSc/BGlobalSt, Marine Science, Global Environment and Sustainable Development

Nick Golledge is a Professor of Glaciology in the Antarctic Research Centre at Victoria University of Wellington. He has written or co-authored over 100 journal articles, and published a popular science book about complex systems, called ‘Feedback’, in 2023. Golledge is a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand.