Decoding Dopamine: From Molecule to Mind

Dopamine and Neuroscience | Aariana Rao

Dopamine is often mischaracterised as the brain’s ‘pleasure chemical’, yet it plays far broader roles across motor, cognitive, hormonal, and peripheral systems. This article explores dopamine from its molecular synthesis and signalling mechanisms to its influence on brain pathways and behaviour. It examines how dopaminergic transmission is regulated, the diversity of dopamine receptors, and the consequences of dysfunction in neurological and psychiatric disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. By tracing dopamine’s pathway from molecule to mind, this review highlights its central role in shaping thought, movement, emotion, and motivation.

Dopamine: An Overview

In everyday life, dopamine is frequently dubbed the brain’s ‘feel-good hormone’ or ‘pleasure chemical’. While not entirely unfounded, this oversimplification belies the true scope and complexity of dopamine’s function. Since its identification in the late 1950s, after it was initially known as a mere precursor to norepinephrine, dopamine has emerged as a critical neuromodulator involved in a broad array of processes, extending far beyond pleasure and reward [1]. It plays key roles in motor control, cognition, hormonal regulation, and even peripheral systems such as the gastrointestinal tract [2]. Although dopamine-producing neurons make up a very small percentage of the brain’s total neuronal population, they project extensively and modulate wide-ranging neural circuits. These networks govern essential functions including voluntary movement, reinforcement learning, decision-making, time perception, and autonomic regulation. Far from being just a chemical of pleasure, dopamine is a central architect of behaviour, physiology, and perception [2-4].

Disruption of dopaminergic signalling is implicated in a broad spectrum of neurological and psychiatric disorders. In Parkinson’s disease (PD), the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra gives rise to hallmark motor symptoms such as tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia [5]. In contrast, hyperactivity of dopaminergic pathways, particularly in the mesolimbic system, has been linked to the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, including hallucinations and delusions [6]. Beyond these, aberrant dopamine function is also associated with mood disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), substance use disorders, and metabolic and endocrine dysfunctions. These diverse clinical consequences underlie dopamine’s far-reaching influence across nearly every domain of brain, body, and function [5, 6].

Molecular Characteristics and Biosynthesis of Dopamine

Neurotransmitters such as dopamine, glutamate, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) can be classified by their molecular identity into categories including small organic molecules, peptides, monoamines, nucleotides, and amino acids [2]. They are also functionally characterised as either excitatory or inhibitory. Monoamines, including dopamine, share several biochemical properties: they are small, charged molecules that generally do not cross the blood-brain barrier, are synthesised from amino acids via short metabolic pathways, and are regulated by a single rate-limiting enzymatic step. Typically, monoamines act through metabotropic receptors and exert slower, modulatory effects compared to the rapid synaptic transmission mediated by glutamate and GABA [2, 6].

Catecholamines are a subgroup of monoamines distinguished by a catechol structure - a benzene ring with two hydroxyl groups and a side-chain amine. Dopamine, or 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethylamine, shares this structure and plays a key role in central nervous system (CNS) signalling and the regulation of various physiological functions. Alongside norepinephrine and epinephrine, dopamine belongs to the catecholamine family and contributes significantly to stress responses, arousal, and neuromodulation [7].

Dopamine synthesis involves two main enzymatic steps, beginning with the amino acid precursor tyrosine. Although phenylalanine can be converted to tyrosine via phenylalanine hydroxylase, dopamine biosynthesis is generally considered to start with tyrosine. Tyrosine is hydroxylated by tyrosine hydroxylase to form L-dopa, or 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine [2, 6, 7]. This hydroxylation occurs at the meta (1, 3) position of the benzene ring. L-dopa is converted to dopamine via the L-aromatic amino acid carboxylase. Under physiological conditions, tyrosine hydroxylase is saturated with its substrate, meaning that increasing tyrosine levels does not typically enhance dopamine production. As such, tyrosine hydroxylase represents the rate-limiting step in dopamine synthesis and tightly regulates intracellular dopamine concentrations [7].

Activation of dopaminergic neurons increases tyrosine hydroxylase activity, thereby elevating dopamine synthesis and release. This regulation occurs at both short- and long-term levels: short-term control is mediated by post-translational modifications of the enzyme, while longterm regulation involves transcriptional control of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene [7]. The gene’s expression can be modulated by various pharmacological agents, including nicotine, caffeine, morphine, and certain antidepressants, which influence transcriptional activators and repressors acting on tyrosine hydroxylase promoter regions [7].

Neurochemical Dynamics at the Dopaminergic Synapse

Dopamine synthesis occurs in the cytoplasm of presynaptic terminals, where synthetic enzymes are transported from the soma. Newly synthesised dopamine is packaged into synaptic vesicles by vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) proteins, with VMAT2 being the predominant isoform in dopaminergic neurons [7]. These vesicles, which are densely concentrated in nerve terminals, protect dopamine from enzymatic degradation and prevent passive diffusion from the neuron. Once primed, they undergo membrane fusion and exocytosis in response to depolarisation [7].

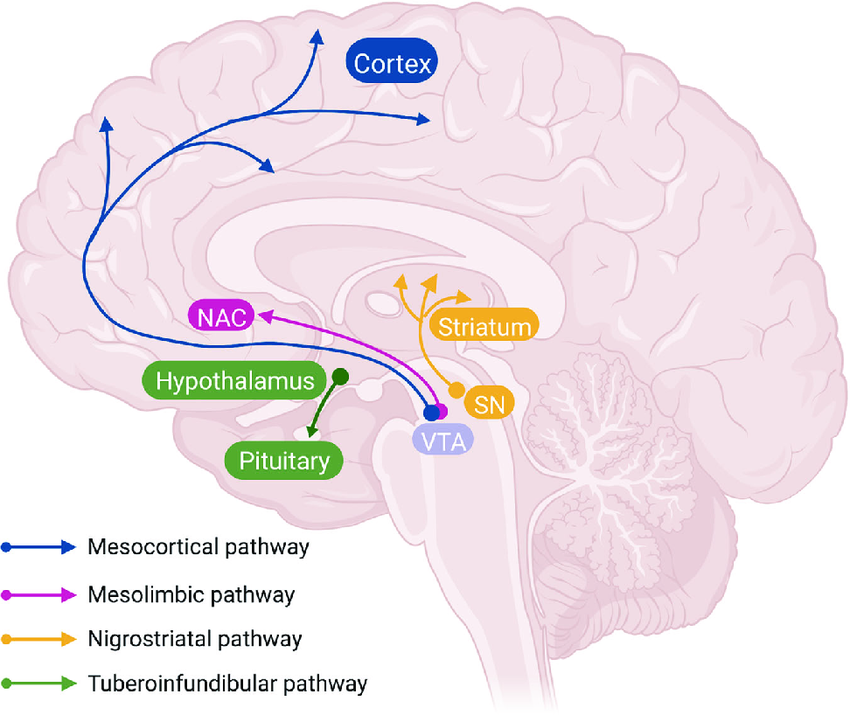

Figure 2: Diagram of the major dopaminergic pathways in the brain. The mesocortical pathway (blue) projects from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the prefrontal cortex. The mesolimbic pathway (pink) extends from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and limbic structures. The nigrostriatal pathway (yellow) connects the substantia nigra to the dorsal striatum. The tuberoinfundibular pathway (green) projects from hypothalamic nuclei (arcuate and periventricular) to the anterior pituitary gland [15].

Clinical Consequences of Dopaminergic Dysfunction

Dopamine plays diverse and critical roles in both health and disease, with disruptions to its signalling pathways contributing to a wide range of neurological, psychiatric, and systemic disorders. These pathways form highly regulated circuits essential for maintaining physiological balance and overall well-being [2, 17]. Dysregulation of dopaminergic signalling has been implicated in several pathologies, including neurodegenerative diseases such as PD, psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and addiction, and complex behavioural conditions like ADHD [2, 17].

PD is the most prevalent neurodegenerative movement disorder, resulting from the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc and the accumulation of Lewy bodies, which are rich in alpha synuclein. It predominantly affects individuals over the age of 60 and occurs more frequently in men than women. While dopaminergic neuronal decline occurs as part of normal ageing, PD is characterised by an accelerated loss, with clinical symptoms typically emerging once dopaminergic neurons and striatal terminals are reduced by approximately 40-50% [2, 17].

The classical model of PD pathophysiology centres on disrupted basal ganglia circuitry. A reduction in dopamine levels decreases activity in the direct pathway and enhances the indirect pathway, leading to diminished thalamocortical output and resulting in parkinsonian motor symptoms, including the hallmark bradykinesia, rigidity, and resting tremors [2, 17]. Beyond motor impairments, PD is also associated with cognitive inflexibility, likely due to dysfunction within dopamine-modulated cortico-striatal circuits, particularly involving the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. These regions are integral to processing the motivational value of stimuli, and altered dopamine signalling here contributes to non-motor symptoms and reduced cognitive adaptability [17].

Schizophrenia is a complex psychiatric disorder characterised by a heterogenous constellation of positive (e.g. hallucination, disorganised speech), negative (e.g. apathy, social withdrawal), and cognitive (e.g. working memory deficits) symptoms. It affects approximately 1% of the global population, typically with onset in late adolescence, and is more common and severe in men [17]. While the precise neurobiological mechanisms remain elusive, the dopamine hypothesis remains the most prominent explanatory framework. This hypothesis suggests that abnormal dopamine transmission, particularly hyperactivity in D2 receptor signalling, contributes to psychotic and cognitive symptoms [17].

Imaging studies in patients with schizophrenia have consistently shown increased D2 receptor density, without corresponding changes in D1 receptor expression. Antipsychotic medications, which primarily target D2 receptors, are the first-line treatment for managing symptoms. However, a subset of patients exhibit treatment-resistance schizophrenia, with little-to-no response to D2 antagonists [17]. This resistance is thought to result from complex mechanisms, including altered dopamine synthesis and release, abnormal receptor affinity states, and downstream signalling dysfunction. Increased D2 receptor density, especially in high-affinity concentrations, may also reduce treatment efficacy [17].

ADHD is one of the most common childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorders, with a global prevalence of approximately 5% in children and 2.5% in adults. Symptoms, including inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity, often persist into adolescence and adulthood in up to 80% of affected individuals. ADHD has a strong genetic component and a multifactorial etiology involving dysregulation of catecholaminergic systems [2].

Animal models and human neuroimaging studies suggest dopaminergic dysfunction as a key contributor to ADHD pathophysiology, particularly in frontal lobe circuits associated with executive function and behavioural regulation. Genetic studies have implicated polymorphisms in genes encoding components of the catecholaminergic system, including DAT, D4 and D5 receptors, and norepinephrine transporters [2]. Abnormal DAT expression has been observed in individuals with ADHD, and DAT remains a primary pharmacological target of psychostimulant medications such as amphetamine. Additionally, D4 and D5 receptor subtypes are enriched in brain regions implicated in ADHD, further supporting their role in the disorder’s neurobiology [2].

A Final Note on Dopaminergic Complexity

Dopamine is far more than a ‘pleasure chemical’, it is a neuromodulator essential to the brain’s functional architecture and the body’s physiological balance. From its synthesis at the molecular level to its role in orchestrating complex behaviours and regulating endocrine pathways, dopamine exerts widespread and finely tuned control over neural communication. Its influence spans voluntary movement, reward learning, decision-making, emotional processing, hormonal regulation, and even peripheral systems.

The complexity of dopaminergic signalling, through multiple pathways, receptor subtypes, and temporal modes of release, underpins both its versatility and its vulnerability. Dysregulation within this system contributes to a range of disorders, from PD to schizophrenia to ADHD and addiction. Understanding dopamine’s diverse functions and transmission dynamics not only sheds light on the neurobiology of behaviour but also informs clinical approaches to treating dopaminergic dysfunction. As research continues to unravel the molecular and circuit-level intricacies of dopamine, new insights will further illuminate its role as a key mediator linking molecule, mind, and body.

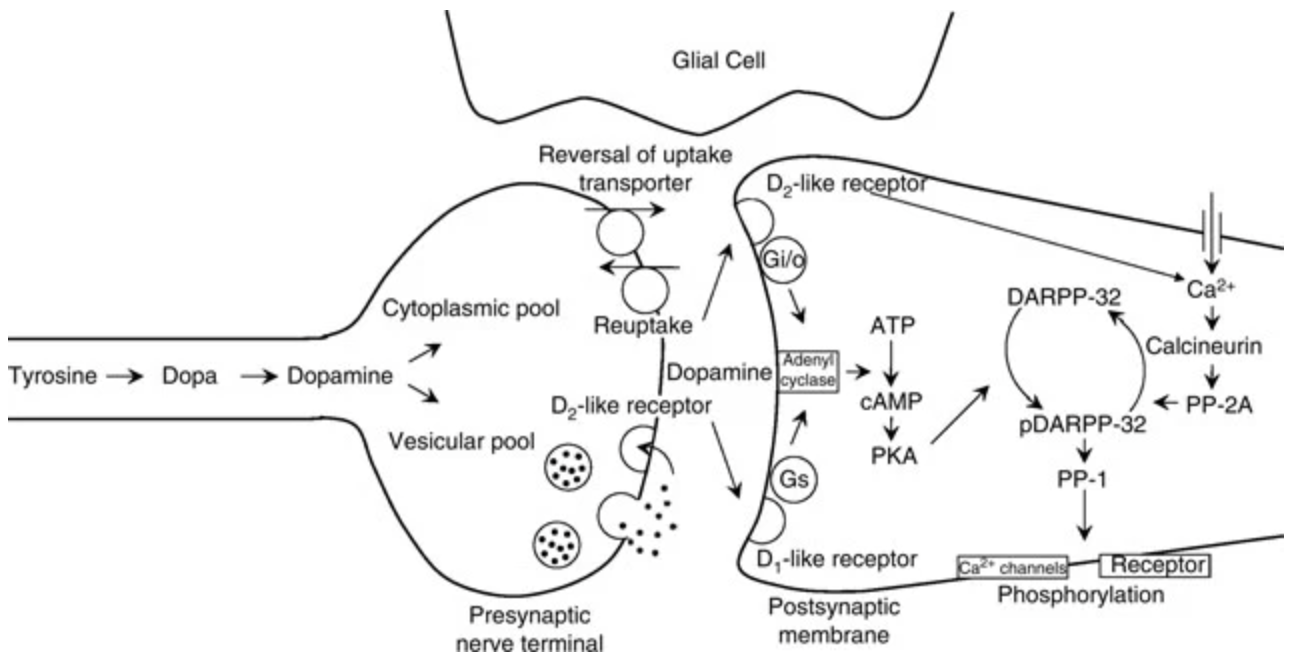

Figure 1: A schematic of the dopaminergic synapse, including the presynaptic terminal, synaptic cleft, and postsynaptic cell. Dopamine is released from presynaptic terminals and binds to presynaptic D2 autoreceptors, which inhibit further neurotransmitter release. Activation of these receptors suppresses cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production and inhibits protein kinase A (PKA), thereby regulating proteins involved in the release machinery. Dopamine-releasing drugs enter presynaptic terminals and, in the presence of elevated sodium ion concentrations, reverse dopamine transporter function, causing dopamine efflux into the synaptic cleft [7].

VMAT2 facilitates the active transport of dopamine into synaptic vesicles for release into the synaptic cleft. Five dopamine receptor subtypes have been identified, all of which are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). These are classified into two families: D1-like (D1, D5) and D2-like (D2, D3, D4) [6, 8, 10]. D1-like receptors couple to Gs and Golf proteins, stimulating adenylate cyclase, which converts adenosine triphosphate (ATP) into cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). This cascade activates protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), leading to CREB-dependent gene transcription involved in synaptic plasticity. D1-like receptors also modulate ion channels, including voltage-gated sodium, potassium, and calcium channels, as well as G-protein gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels [6, 8, 10]. These mechanisms are illustrated in the postsynaptic region of Figure 1.

In contrast, D2-like receptors couple to inhibitory Gi/o proteins, suppressing adenylate cyclase and downstream PKA activity. They also activate GIRK channels and inhibit voltage-gated calcium channels, thereby reducing neuronal excitability [6, 8, 10].

A key integrator in dopamine signalling is 32-kilodalton dopamine and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein (DARPP-32), which is highly expressed in striatal and cortical dopaminoceptive neurons. DARPP-32 integrates signalling from multiple neurotransmitter systems and modulates downstream pathways in circuits such as the nigrostriatal and mesolimbic systems [9-11]. Depending on the phosphorylation state, DARPP-32 can enhance PKA signalling by inhibiting protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), or suppress it via dephosphorylation through calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B), enabling bidirectional control of dopaminergic signal transduction [9-11].

Plasma Membrane Transport: Dopamine Regulation via the Dopamine Transporter

Dopamine transport across the plasma membrane is essential for both neurotransmission and intracellular compartmentalisation [8, 12]. This process is mediated by dopamine transporters (DAT), which are expressed on dopaminergic neurons and facilitate the active reuptake of dopamine by coupling its transport with the movement of two sodium ions and one chloride ion down their electrochemical gradient. These gradients are maintained by the sodium-potassium ATPase, which provides the driving force for DAT function [8, 12]. DAT-mediated dopamine uptake involves a series of conformational changes. The uptake cycle begins with DAT in an outward-facing conformation, allowing sodium and chloride ions to bind [8, 12]. Once dopamine binds to this pre-loaded complex, the extracellular gate closes, triggering a shift to an inward-facing state. Dopamine and the co-transported ions are then released into the cytosol, and the transporter resets to its original conformation to repeat the cycle [8, 12].

The primary role of DAT is to clear dopamine from the synaptic cleft and transport it into the cytoplasm of presynaptic neurons. Localised near synapses, DAT enables precise spatial and temporal regulation of dopaminergic signalling. In regions such as the striatum and nucleus accumbens, DAT is the principal mechanism for terminating synaptic dopamine activity [8, 12]. In addition to removing extracellular dopamine, DAT also recycles it for subsequent storage and release, as illustrated in Figure 1 at the presynaptic terminal. By facilitating cytosolic dopamine accumulation, DAT not only modulates extracellular dopamine concentrations but also indirectly regulates vesicular dopamine content, thereby shaping the overall dynamics of dopamine signalling within the neuron [8, 12].

Vesicular Membrane Transport: Dopamine Packaging via VMAT2

Neurotransmission depends on the proper storage and release of neurotransmitters from synaptic vesicles. These small, spherical lipid bilayers are formed in the Golgi apparatus and transported to the synaptic terminal, where they concentrate and package neurotransmitters for release during synaptic signalling [8, 13]. The majority of neurotransmitters in the brain are sequestered within these vesicles, making vesicular storage a key determinant of neurotransmitter availability. High concentrations of neurotransmitters are actively loaded into the vesicle lumen via transport mechanisms powered by a vacuolar proton pump, which generates an electrochemical gradient and occupies approximately 10% of the vesicle’s volume [8, 13].

VMAT2 is responsible for the packaging of cytosolic monoamines, including dopamine, into small synaptic and dense-core vesicles in monoaminergic neurons throughout the brain. VMAT2 belongs to the solute carrier family 18 (SLC18), along with VMAT1 [8, 13]. As a hydrogen ion-ATPase antiporter, VMAT2 harnesses the vesicular electrochemical gradient to drive monoamine transport. This gradient is established by the vacuolar hydrogen ion-ATPase, which hydrolyses ATP to actively pump protons into the vesicle, generating an acidic environment with an internal pH of approximately 5.5 [8, 13]. The resulting proton gradient enables VMAT2 to import monoamines into the vesicle lumen by exchanging each transported monoamine molecule for two protons expelled into the cytosol. Through this mechanism, VMAT2 plays a critical role in regulating dopamine availability at the synaptic terminal by ensuring the efficient sequestration of neurotransmitters into vesicles for subsequent release [8, 13].

Mechanisms of Dopaminergic Transmission

Dopaminergic signalling operates primarily through two mechanisms: synaptic transmission and volume transmission. In synaptic transmission, dopamine is released from vesicles into the synaptic cleft and acts on nearby receptors. Following release, dopamine is cleared from the extracellular space by dopamine transporters (DAT), which import it into the presynaptic cytosol [6, 8, 10]. There, VMAT2 repackages the cytosolic dopamine into synaptic vesicles for future release. DAT and VMAT2 function in tandem to facilitate efficient neurotransmitter trafficking throughout the neuron. This compartmentalisation is critical, as cytosolic accumulation of dopamine can contribute to oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Synaptic transmission primarily involves D1-like and D2-like dopamine receptors, which regulate intracellular pathways such as cAMP production, PKA activation, and the modulation of voltage-gated ion channels [6, 8, 10].

In contrast, volume transmission is not confined to traditional synaptic connections and allows dopamine to diffuse over broader distances. It often involves non-synaptic release mechanisms, where a single exocytotic event can influence multiple target cells if their receptors lie within diffusion range [14]. Upon vesicular fusion, dopamine is released from a point source and rapidly disperses through the extracellular space. The resulting signal is shaped by multiple factors, including diffusion, buffering, reuptake, and enzymatic degradation. These processes generate dynamic, spatiotemporal gradients of transmitter concentration that are essential for effective receptor activation [14].

Dopamine signalling is further modulated by phasic and tonic transmission. Phasic transmission involves burst firing of dopaminergic neurons, producing transient, high concentration dopamine spikes near the synapse. In contrast, tonic transmission reflects a lower, baseline level of extracellular dopamine, regulated independently of action potentials and influenced by ongoing reuptake and surrounding neuronal activity [2]. Phasic dopamine release occurs on a millisecond timescale and can saturate D2 receptors, whereas tonic transmission unfolds over seconds to minutes and typically maintains nanomolar concentrations. Although tonic levels are lower, they are sufficient to activate presynaptic D2 autoreceptors, which modulate subsequent dopamine release [2].

In most brain regions, dopamine release occurs via exocytosis triggered by changes in membrane potential. Unlike classical fast neurotransmission, dopamine is frequently released through volume transmission, diffusing across broader extracellular spaces to modulate activity in multiple cells [2]. In the striatum, dopamine release is localised to sparse axonal hotspots with active zone-like specialisations that enable precise release. Once in the extracellular space, dopamine can bind to postsynaptic receptors on dendrites and soma, or to presynaptic D2 and D3 autoreceptors that modulate neuronal firing. Following receptor activation, dopamine rapidly dissociates and is cleared by DAT or other monoamine transporters, terminating its signal [2].

Major Dopaminergic Pathways of the Brain

Dopaminergic signalling in the mammalian CNS is primarily mediated by three major pathways: the nigrostriatal, mesolimbic, and mesocortical circuits, which are governed by midbrain dopaminergic neurons located in the substantia nigra and VTA. A fourth pathway, the tuberoinfundibular circuit, is also part of the dopaminergic system.

The nigrostriatal pathway, highlighted in yellow in Figure 2, originates in the substantia nigra pars compacta and projects to the caudate and putamen nuclei of the dorsal striatum. It plays a central role in motor control and motor skill learning. Dopaminergic degeneration in this circuit is characteristic of Parkinson’s disease (PD), leading to bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremors. Conversely, excess dopamine activity in this region has been implicated in hyperkinetic disorders, such as tics or chorea, characterised by involuntary and excessive movement [6].

The mesolimbic pathway, illustrated in pink in Figure 2, originates in the VTA and projects to the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and parts of the prefrontal cortex. Dopaminergic innervation of the amygdala and cingulate cortex contributes to the processing of emotional responses, while inputs to the hippocampus support learning and memory formation [6]. Dopamine release in the ventral striatum and prefrontal cortex enhances motivation and reward-seeking behaviours, shaping responses to pleasurable stimuli. This pathway underpins the brain’s reward system, supporting experience-dependent learning and the reinforcement of behaviours critical for survival and reproduction [6].

The mesocortical pathway, shown in blue in Figure 2, also originates from the VTA and projects to the prefrontal cortex, which governs executive functions such as planning, attention, and decision-making. Dopamine dysregulation in this circuit has been linked to cognitive impairments seen in disorders such as schizophrenia and ADHD, where reductions in dopaminergic tone may blunt behavioural responses to external stimuli [6].

The tuberoinfundibular pathway, marked in University of Auckland Scientific, August 2025, Vol. 5, No. 3 Scientific 65 green in Figure 2, is functionally distinct from the other three. This neuroendocrine pathway begins in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and projects to the anterior pituitary [16]. Here, dopamine acts as a tonic inhibitor of prolactin secretion by acting on lactotroph cells. In contrast to the other dopaminergic circuits, the tuberoinfundibular pathway plays a crucial role in maintaining hormonal homeostasis, linking brain activity with reproductive and metabolic regulation, and highlighting the integrative communication between the nervous and endocrine systems [16].

[1] V. Yeragani, M. Tancer, P. Chokka, and G. Baker, “Arvid Carlsson, and the story of dopamine,” Indian Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 52, no. 1, 2010, doi: 10.4103/0019- 5545.58907.

[2] M. O. Klein, D. S. Battagello, A. R. Cardoso, D. N. Hauser, J. C. Bittencourt, and R. G. Correa, “Dopamine: Functions, Signaling, and Association with Neurological Diseases,” Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, vol. 39, no. 1. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10571-018- 0632-3.

[3] H. Juárez Olguín, D. Calderón Guzmán, E. Hernández García, and G. Barragán Mejía, “The role of dopamine and its dysfunction as a consequence of oxidative stress,” Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, vol. 2016. 2016. doi: 10.1155/2016/9730467.

[4] R. G. Nair-Roberts, S. D. ChatelainBadie, E. Benson, H. White-Cooper, J. P. Bolam, and M. A. Ungless, “Stereological estimates of dopaminergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra and retrorubral field in the rat,” Neuroscience, vol. 152, no. 4, 2008, doi: 10.1016/j. neuroscience.2008.01.046.

[5] C. M. Tanner and J. L. Ostrem, “Parkinson’s Disease,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 391, no. 5, pp. 442–452, Aug. 2024, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2401857. [6] L. Speranza, U. di Porzio, D. Viggiano, A. de Donato, and F. Volpicelli, “Dopamine: The neuromodulator of long-term synaptic plasticity, reward and movement control,” Cells, vol. 10, no. 4. 2021. doi: 10.3390/ cells10040735.

[7] L. G. Harsing, “Dopamine and the Dopaminergic Systems of the Brain,” in Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology, 2008. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-30382-6_7.

[8] K. M. Lohr, S. T. Masoud, A. Salahpour, and G. W. Miller, “Membrane transporters as mediators of synaptic dopamine dynamics: implications for disease,” European Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 45, no. 1, 2017, doi: 10.1111/ejn.13357.

[9] R. Franco, I. Reyes-Resina, and G. Navarro, “Dopamine in health and disease: Much more than a neurotransmitter,” Biomedicines, vol. 9, no. 2. 2021. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9020109.

[10] N. X. Tritsch and B. L. Sabatini, “Dopaminergic Modulation of Synaptic Transmission in Cortex and Striatum,” Neuron, vol. 76, no. 1. 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.023.

[11] X. Zhang, D. Tsuboi, Y. Funahashi, Y. Yamahashi, K. Kaibuchi, and T. Nagai, “Phosphorylation Signals Downstream of Dopamine Receptors in Emotional Behaviors: Association with Preference and Avoidance,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 19. 2022. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911643.

[12] V. Leviel, “Dopamine release mediated by the dopamine transporter, facts and consequences,” Journal of Neurochemistry, vol. 118, no. 4. 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07335.x.

[13] C. L. German, M. G. Baladi, L. M. McFadden, G. R. Hanson, and A. E. Fleckenstein, “Regulation of the dopamine and vesicular monoamine transporters: Pharmacological targets and implications for disease,” Pharmacological Reviews, vol. 67, no. 4. 2015. doi: 10.1124/ pr.114.010397.

[14] Ö. D. Özçete, A. Banerjee, and P. S. Kaeser, “Mechanisms of neuromodulatory volume transmission,” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 29, no. 11, pp. 3680–3693, Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41380-024-02608-3.

[15] H. Xu and F. Yang, “The interplay of dopamine metabolism abnormalities and mitochondrial defects in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia,” Translational Psychiatry, vol. 12, no. 1. 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-02233-0.

[16] X. Qi-Lytle, S. Sayers, and E. J. Wagner, “Current Review of the Function and Regulation of Tuberoinfundibular Dopamine Neurons,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 25, no. 1. 2024. doi: 10.3390/ijms25010110.

[17] L. Speranza, M. C. Miniaci, and F. Volpicelli, “The Role of Dopamine in Neurological, Psychiatric, and Metabolic Disorders and Cancer: A Complex Web of Interactions,” Biomedicines, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 492, Feb. 2025, doi: 10.3390/biomedicines13020492.

Aariana is doing her Masters in Biomedical Science this year. She’s passionate about neuroscience, neuropsychology, and exploring how brain biology shapes human behaviour. Outside of university, she can usually be found curled up with a good book.